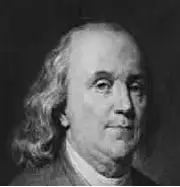

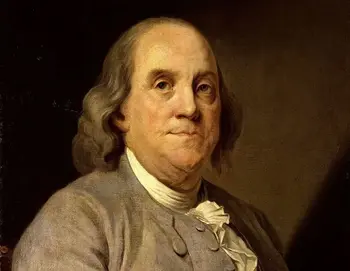

Did Ben Franklin Really Discover Electricity?

Ben Franklin Discover Electricity explores the kite experiment, lightning, Leyden jar capacitors, static charge, conductors, grounding, and electrostatics, linking early voltage insights to modern electrical engineering and circuit safety principles.

What Does Ben Franklin Discover Electricity Mean?

Franklin's kite test tied lightning to electrostatics, showing charge, grounding, and conductor behavior for engineers.

✅ Modeled lightning as electrical discharge using a grounded conductor.

✅ Captured charge with a Leyden jar capacitor to measure potential.

✅ Inspired grounding, insulation, and surge protection design.

It is the common belief that Ben Franklin "discovered" electricity. Modern historians clarify in this discussion of who discovered electricity that discovery was a gradual process involving many thinkers.

In fact, electricity did not begin when Benjamin Franklin flew his kite during a thunderstorm or when light bulbs were installed in houses all around the world. For broader context, see a concise history of electricity that traces developments long before Franklin's era.

"His observations," says Dr. Stuber, "he communicated, in a series of letters, to his friend Collinson, the first of which is dated March 28, 1747. In these he shows the power of points in drawing and throwing off the electrical matter which had hitherto escaped the notice of electricians. He also made the grand discovery of a plus and minus, or of a positive and negative, state of electricity. We give him the honor of this without hesitation; although the English have claimed it for their countryman, Dr. Watson. Watson's paper is dated January 21, 1748; Franklin's July 11, 1747, several months prior. Shortly after Franklin, from his principles of the plus and minus state, explained in a satisfactory manner the phenomena of the Leyden vial, first observed by Mr. Cuneus, or by Professor Muschenbroeck, of Leyden, which had much perplexed philosophers. He showed clearly that when charged the bottle contained no more electricity than before, but that as much was taken from one side as was thrown on the other; and that to discharge it nothing was necessary but to produce a communication between the two sides, by which the equilibrium might be restored, and that then no sign of electricity would remain. He afterward demonstrated by experiments that the electricity did not reside in the coating, as had been supposed, but in the pores of the glass itself. After a vial was charged he removed the coating, and found that upon applying a new coating the shock might still be received. In the year 1749 he first suggested his idea of explaining the phenomena of thunder-gusts and of the aurora borealis upon electrical principles. He points out many particulars in which lightning and electricity agree, and he adduces many facts, and reasonings from facts, in support of his positions.

These ideas also foreshadow links between charge, fields, and induction outlined in foundational electricity and magnetism resources that situate Franklin's work within later theory.

"In the same year he received the astonishingly bold and grand idea of ascertaining the truth of his doctrine by actually drawing down the lightning, by means of sharp-pointed iron rods raised into the region of the clouds. Even in this uncertain state his passion to be useful to mankind displayed itself in a powerful manner. Admitting the identity of electricity and lightning, and knowing the power of points in repelling bodies charged with electricity, and in conducting their fires silently and imperceptibly, he suggested the idea of securing houses, ships, etc., from being damaged by lightning, by erecting pointed rods that should rise some feet above the most elevated part, and descend some feet into the ground or water. The effect of these he concluded would be either to prevent a stroke by repelling the cloud beyond the striking distance, or by drawing off the electrical fire which it contained; or, if they could not effect this, they would at least conduct the electric matter to the earth without any injury to the building.

Practical consequences of these insights are summarized in an overview of Franklin's contributions to electricity that explains the lightning rod's impact on public safety.

"It was not till the summer of 1752 that he was enabled to complete his grand and unparalleled discovery by experiment. The plan which he had originally proposed was to erect, on some high tower or other elevated place, a sentry-box, from which should rise a pointed iron rod, insulated by being fixed in a cake of resin. Electrified clouds passing over this would, he conceived, impart to it a portion of their electricity, which would be rendered evident to the senses by sparks being emitted when a key, the knuckle, or other conductor was presented to it. Philadelphia at this time afforded no opportunity of trying an experiment of this kind. While Franklin was waiting for the erection of a spire, it occurred to him that he might have more ready access to the region of clouds by means of a common kite. He prepared one by fastening two cross sticks to a silken handkerchief, which would not suffer so much from the rain as paper. To the upright stick was affixed an iron point. The string was, as usual, of hemp, except the lower end, which was silk. Where the hempen string terminated, a key was fastened. With this apparatus, on the appearance of a thunder-gust approaching he went out into the commons, accompanied by his son, to whom alone he communicated his intentions, well knowing the ridicule which, too generally for the interest of science, awaits unsuccessful experiments in philosophy. He placed himself under a shed, to avoid the rain; his kite was raised, a thunder-cloud passed over it, no sign of electricity appeared. He almost despaired of success, when suddenly he observed the loose fibres of his string to move toward an erect position. He now presented his knuckle to the key and received a strong spark. How exquisite must his sensations have been at this moment! On this experiment depended the fate of his theory. If he succeeded, his name would rank high among those who had improved science; if he failed, he must inevitably be subjected to the derision of mankind, or, what is worse, their pity, as a well-meaning man, but a weak, silly projector. The anxiety with which he looked for the result of his experiment may be easily conceived. Doubts and despair had begun to prevail, when the fact was ascertained, in so clear a manner that even the most incredulous could no longer withhold their assent. Repeated sparks were drawn from the key, a vial was charged, a shock given, and all the experiments made which are usually performed with electricity.

This experiment is often positioned on timelines such as a chronology of electricity's history that maps how one breakthrough enabled the next.

"About a month before this period some ingenious Frenchman had completed the discovery in the manner originally proposed by Dr. Franklin. The letters which he sent to Mr. Collinson, it is said, were refused a place in the Transactions of the Royal Society of London. However this may be, Collinson published them in a separate volume, under the title of New Experiments and Observations on Electricity, made at Philadelphia, in America. They were read with avidity, and soon translated into different languages. A very incorrect French translation fell into the hands of the celebrated Buffon, who, notwithstanding the disadvantages under which the work labored, was much pleased with it, and repeated the experiments with success. He prevailed on his friend, M. Dalibard, to give his countrymen a more correct translation of the works of the American electrician. This contributed much toward spreading a knowledge of Franklin's principles in France. The King, Louis XV, hearing of these experiments, expressed a wish to be a spectator of them. A course of experiments was given at the seat of the Duc d'Ayen, at St. Germain, by M. de Lor. The applause which the King bestowed upon Franklin excited in Buffon, Dalibard, and De Lor an earnest desire of ascertaining the truth of his theory of thunder-gusts. Buffon erected his apparatus on the tower of Montbar, M. Dalibard at Marly-la-Ville, and De Lor at his house in the Estrapade at Paris, some of the highest ground in that capital. Dalibard's machine first showed signs of electricity. On May 16, 1752, a thunder-cloud passed over it, in the absence of M. Dalibard, and a number of sparks were drawn from it by Coiffier, joiner, with whom Dalibard had left directions how to proceed and by M. Paulet, the prior of Marly-la-Ville.

"An account of this experiment was given to the Royal Academy of Sciences, by M. Dalibard, in a memoir dated May 13, 1752. On May 18th, M. de Lor proved equally as successful with the apparatus erected at his own house. These philosophers soon excited those of other parts of Europe to repeat the experiment; among whom none signalized themselves more than Father Beccaria, of Turin, to whose observations science is much indebted. Even the cold regions of Russia were penetrated by the ardor of discovery. Professor Richmann bade fair to add much to the stock of knowledge on this subject, when an unfortunate flash from his conductor put a period to his existence.

Such international replication also illuminates the distinction between discovery and invention discussed in analyses of who invented electricity that parse credit across different achievements.

"By these experiments Franklin's theory was established in the most convincing manner.

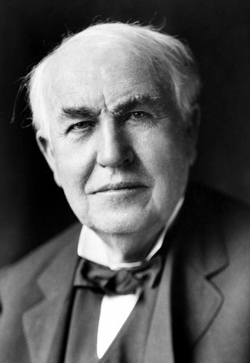

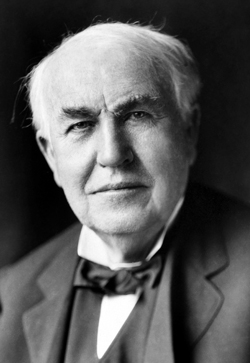

Later innovators including Edison would translate this scientific understanding into widespread applications described in accounts of Thomas Edison's work with electricity that trace the path from lab to industry.