History of Electricity

By R.W. Hurst, Editor

The history of electricity traces discoveries from ancient static charges to modern power grids. Key milestones include Franklin’s lightning experiments, Volta’s battery, and Edison’s light bulb, laying the foundation for today’s electrical energy, distribution systems, and innovation.

What is the History of Electricity?

The history of electricity reveals how scientific discoveries evolved into practical technologies that power the modern world.

✅ Tracks early observations of electric charge and static electricity

✅ Highlights discoveries by pioneers like Franklin, Volta, and Edison

✅ Shows how electric power systems shaped modern life

Our comprehensive electricity history guide breaks down major inventions and the rise of electrical infrastructure. Curious about the origins? Explore our detailed timeline of electricity discoveries, from ancient Greek observations to global electrification.

How It Transformed Human Civilization: From Curiosity to Power Grid

Long before it was understood, it was felt—a crackling jolt from a sweater, a lightning strike in the sky, the pull of a magnet. These mysterious forces inspired awe, fear, and speculation. Early humans saw them as magic, omens, or divine power.

Around 600 BC, Greek philosopher Thales of Miletus observed that rubbing amber (or elektron) with fur caused it to attract small objects. This was static electricity, though no one knew it yet. The word electricity would later come from that same Greek root.

It wasn’t until the early 1600s that electrical energy began its transformation from myth to science. English scientist William Gilbert, in his book De Magnete, coined the term electricus and distinguished magnetic forces from electrical attraction. He introduced experimentation and laid the groundwork for future inquiry.

For centuries, electromagnetism was nature’s secret—lightning in the sky, sparks on contact, strange forces pulling and pushing. It would take time, and many curious minds, to turn this invisible energy into a force that could change the world.

Curiosity Turns to Science

By the 18th century, electric current was more than a curiosity, it was becoming a science. Benjamin Franklin, fascinated by lightning, wondered if it was the same as static electricity. In 1752, his legendary kite experiment proved it was. A key attached to the string sparked during the storm, confirming that lightning was electrical in nature. Franklin’s bold curiosity led to practical inventions like the lightning rod and sparked wider interest in harnessing electric power.

Benjamin Franklin

Learn how Ben Franklin discovered electricity through his iconic kite experiment and helped define lightning as an electrical force. For a deeper dive into Franklin’s work, see our dedicated article on Ben Franklin and electricity, which outlines his groundbreaking theories.

Meanwhile, in Italy, a different kind of electrical mystery was unfolding. In 1786, Luigi Galvani discovered that a dead frog’s leg twitched when touched with a metal scalpel. He believed this was “animal electricity”, a life force stored in living tissue.

But Alessandro Volta disagreed. He argued the twitch was caused by two dissimilar metals and moisture, creating a chemical reaction that produced an electric current. To prove it, he invented the voltaic pile, the first true battery—a steady, flowing source of electrical energy that could be used in experiments.

Alessandro Volta

This rivalry—Galvani’s biological theory versus Volta’s chemical one—marked a turning point. For the first time, electrical energy could be created, stored, and controlled. Franklin had shown that electrical energy was a natural force; Volta showed it could become a practical power source. And with that, electric energy began its transformation from phenomenon to technology. Compare how electricity was discovered with who invented electricity and its impact on shaping the modern world.

From Sparks to Power — The Invention of Continuous Current

For centuries, electric current appeared only in flashes—unpredictable and temporary. It sparked from rubbed amber, jumped between metal objects, or roared across the sky as lightning. Scientists had learned to generate and store static electricity, but no one could create a steady, usable flow. That changed in 1800, when Alessandro Volta invented the voltaic pile—a stack of zinc and copper discs separated by salt-soaked cloth. It was the world’s first battery, and it marked a seismic shift in the understanding and use of electric power.

Volta’s device didn’t just shock or spark—it produced a continuous current, something new and astonishing. With it, electrical energy became a resource rather than a curiosity. For the first time, electric energy could be controlled, repeated, and studied in depth. This breakthrough allowed scientists to move beyond single moments of discharge and into the study of electrical circuits, potential difference, and chemical reactions that produced steady electron flow.

Electrical energy had changed from a bolt in the sky to a stream you could tap into. This new flow, like a river of electrons, could power devices, light filaments, and eventually drive motors. Volta’s battery became the quiet heartbeat of a new era of invention. Without it, there could be no generators, no industrial electrical power, and no modern power systems.

Lighting the World — Edison, Tesla, and the Grid

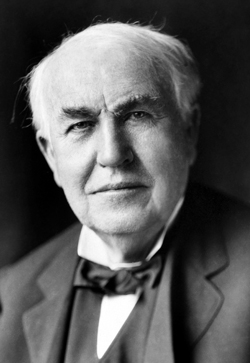

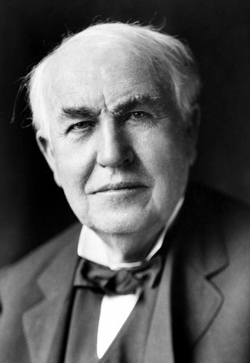

The invention of continuous current sparked a wave of innovation, but it was light that brought electrical power into the lives of ordinary people. In the late 1870s, Thomas Edison designed a practical incandescent bulb, one that could burn for hours and be mass-produced. But lighting a bulb wasn’t enough—he needed a way to deliver power to homes and businesses. That led to the creation of the first central power station, and with it, the beginning of the electrical grid.

Thomas Edison

Read about how Thomas Edison revolutionized electricity by building the first power distribution system in New York City.

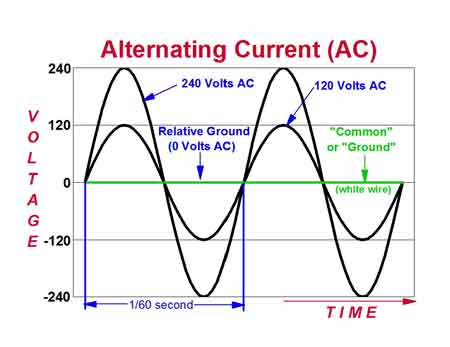

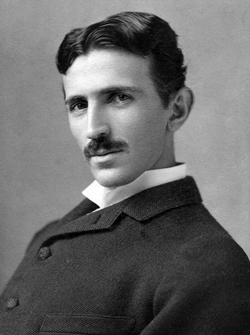

Edison’s system ran on direct current (DC), which could only transmit power a short distance. Enter Nikola Tesla, a brilliant inventor who envisioned a better solution: alternating current (AC). Backed by industrialist George Westinghouse, Tesla’s AC system could send electrical energy miles away with minimal loss. The resulting clash between the two camps became known as the War of Currents—a high-stakes drama of innovation, rivalry, and public persuasion.

In the end, Tesla’s AC system prevailed, and the modern power grid was born. But more than a technical achievement, this was a cultural shift. Darkness no longer ruled the night. Cities glowed. Streets, homes, and factories became connected by invisible power. Electric current had moved from labs and elite workshops into the daily rhythm of life. It changed how we worked, lived, and imagined the future.

Nikola Tesla

From Wires to Wireless — The Communication Revolution

Electrical generation did more than light up cities—it gave humans a way to communicate across time and space. The 19th century saw the invention of the telegraph, powered by simple electric circuits and Morse code. For the first time in history, messages could travel faster than a horse or a ship. The telephone soon followed, allowing real-time voice communication through electric signals carried over wires.

But electrical energy wasn’t the only thing transforming communication. With the discoveries of James Clerk Maxwell and Heinrich Hertz, scientists realized that electrical currents could produce electromagnetic waves—waves that could travel through air without wires. Guglielmo Marconi turned this insight into the world’s first wireless telegraph. Radio was born. Later, electric circuits powered amplifiers, transmitters, and receivers, laying the groundwork for broadcasting, television, and digital electronics.

From sparks to speech, and from wires to wireless, alternating current became the nervous system of the modern world. Nearly every modern communication device—from smartphones to satellites- traces its lineage to these electric breakthroughs. The world became smaller, faster, and more connected, all because humans learned to speak through electrons.

The Invisible Infrastructure

Today, electric power is everywhere, and yet we rarely see it. It hums behind the walls, powers our screens, drives our vehicles, and breathes life into the machines that run modern life. From smartphones to data centers, electric vehicles to traffic lights, power flows silently beneath society’s surface. Without it, cities would darken, hospitals would halt, and the digital world would vanish.

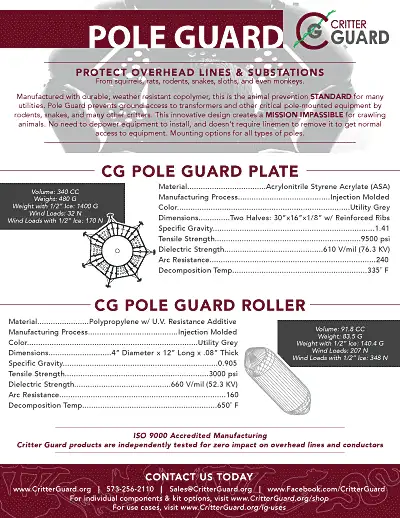

We rely on vast electrical infrastructure—power plants, substations, transformers, and transmission lines—to keep this energy flowing. Most of us never see these systems unless they fail. But behind every light switch and every blinking cursor is a complex dance of generation, transmission, and distribution, orchestrated with precision and scale.

Electrical energy is no longer just a discovery. It is our lifeblood—a silent force that powers not just technology, but modern civilization itself. As essential as water and air, electrical energy underpins every aspect of our lives. It connects, sustains, and defines us. It is the bloodstream of civilization—invisible, indispensable, and always flowing.

Related Articles