New Brunswick policy doomed to fail: group

BERESFORD, NEW BRUNSWICK - The province's new Community Energy Policy is a recipe for failure because the government isn't providing enough funding for new projects to get off the ground, says the Conservation Council of New Brunswick.

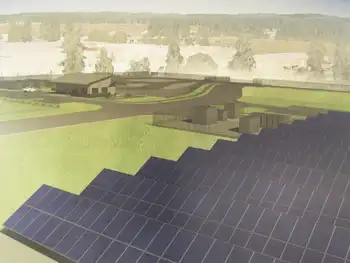

Under the initiative, unveiled in Beresford, 75 megawatts of power from the province's energy portfolio — enough to power up to 15,000 homes — will be reserved for renewable community energy projects, such as wind farms and small hydro dams.

Selected projects will receive 10 cents/ kWh hour for the renewable energy they produce.

But the environmental group contends that's not enough to start new projects.

"They've set their feed-in tariff — the price they'll pay for electricity — below the cost of producing that electricity," said spokesman David Coon.

"So it's not going to drive the development of any community-based renewable energy," he said.

The feed-in tariff will be frozen for the first five years and then escalate with the Consumer Price Index, the province has said.

The community energy policy also drew criticism from Yves Gagnon, one of the people hired to advise the government on community energy during the past three years of consultations.

He said some of his recommendations were adopted, but other crucial elements were left out, such as providing financial and technical support to communities that want to develop a community energy program.

The province plans to hold 11 workshops across the province to educate interested communities about the policy between March 8 and 24.

A request for proposals is scheduled to go out by the end of May. Projects may be based on biomass resources, wind, solar, small hydro or tidal power.

Premier Shawn Graham has said the policy will will help build the energy hub, meet climate change action plan objectives and build expertise in renewable energy in communities across New Brunswick.

Related News

Longer, more frequent outages afflict the U.S. power grid as states fail to prepare for climate change

WASHINGTON - Every time a storm lashes the Carolina coast, the power lines on Tonye Gray’s street go down, cutting her lights and air conditioning. After Hurricane Florence in 2018, Gray went three days with no way to refrigerate medicine for her multiple sclerosis or pump the floodwater out of her basement.

What you need to know about the U.N. climate summit — and why it matters

“Florence was hell,” said Gray, 61, a marketing account manager and Wilmington native who finds herself increasingly frustrated by the city’s vulnerability.

“We’ve had storms long enough in Wilmington and this particular area that all…