Capacitors in series lower the total capacitance but increase voltage handling. This configuration is widely used in electronics, circuit design, and energy storage to balance voltage and improve reliability.

What are Capacitors in Series?

Capacitors in series describe a circuit configuration where capacitors are connected end to end, affecting capacitance and voltage distribution.

✅ The total capacitance is always less than the smallest capacitor value

✅ Voltage divides across each capacitor based on its capacitance

✅ Improves voltage rating of circuits while lowering equivalent capacitance

They play a critical role in various electronic applications, and understanding their characteristics, advantages, and potential drawbacks is essential for designing and implementing successful circuits. By mastering the concepts of capacitance, voltage distribution, and energy storage, one can leverage capacitors in series to create optimal circuit designs. To fully understand how capacitors (caps) behave in different setups, it helps to compare Capacitance in Parallel with series connections and see how each affects circuit performance.

Capacitors are fundamental components in electronic circuits, and their applications are vast, ranging from simple timing circuits to sophisticated filtering applications. This article delves into the intricacies of caps connected in series, highlighting their characteristics, advantages, and potential drawbacks.

To understand capacitors in series, it's essential first to grasp the concept of capacitance, which represents a capacitor's ability to store electric charge. Caps consist of two conductive plates separated by a dielectric material that can store energy when an applied voltage is present. The amount of energy stored depends on the capacitance value, voltage rating, and the dielectric material used. Engineers often study Capacitance and its capacitance definition to calculate charge storage and predict how components will interact in series circuits.

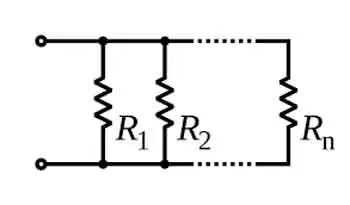

When caps are connected in series, their individual capacitance values contribute to the total equivalent capacitance. The series connection is achieved when the positive plate of one capacitor is connected to the negative plate of the subsequent capacitor. This forms a continuous path for current flow, creating a series circuit.

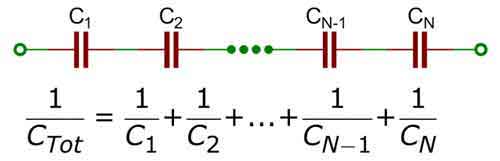

Calculating the total capacitance for capacitors in series is different from parallel capacitors. In a series connection, the reciprocal of the total equivalent capacitance is equal to the sum of the reciprocals of the individual capacitance values. Mathematically, this is represented as:

1/C_total = 1/C1 + 1/C2 + 1/C3 + ... + 1/Cn

Where C_total is the total equivalent capacitance, and C1, C2, C3, ... Cn are the individual capacitance values of the number of caps connected in series.

In a series connection, the electric charge stored in each capacitor is the same. However, the voltage across each capacitor varies depending on its capacitance. According to Kirchhoff's voltage law, the sum of voltages across individual capacitors must equal the applied voltage. Thus, higher capacitance values will have lower voltage drops, while lower capacitance values will have higher voltage drops.

There are both advantages and disadvantages to connecting capacitors in series. On the plus side, the voltage rating of the series connection increases, allowing the circuit to handle higher voltage levels without risking damage to the caps. This feature is particularly useful in high-voltage capacitors in series applications. Alongside capacitors, Amperes Law and Biot Savart Law provide deeper insight into the electromagnetic principles that govern current and voltage distribution.

However, there are also drawbacks to this arrangement. The total equivalent capacitance decreases as more capacitors are added to the series, which may limit the energy storage capabilities of the circuit. Moreover, in the event of a capacitor failure, the entire series connection is compromised.

Different capacitor types and values can be combined in a series configuration, but care must be taken to consider each capacitor's voltage ratings and tolerances. For instance, mixing capacitors with different dielectric materials may lead to uneven voltage distribution and reduced overall performance. Since Capacitors are essential to energy storage and timing circuits, learning their behavior in a Capacitors in Series arrangement is key for advanced electronics design.

Determining the total energy stored in a series connection of caps involves calculating the energy stored in each individual capacitor and then summing those values. The formula for energy storage in a capacitor is:

E = 0.5 * C * V^2

Where E is the energy stored, C is the capacitance, and V is the voltage across the capacitor. Calculating each capacitor's energy and adding the results can determine the total energy stored in the series connection.

Compared with parallel configurations, the total capacitance increases in parallel connections while it decreases in series. In parallel, the total capacitance is the sum of the individual capacitance values:

C_total = C1 + C2 + C3 + ... + Cn

A crucial aspect of working with capacitors in series is charge distribution. As mentioned earlier, the electric charge stored in each capacitor is the same, but the voltage distribution varies depending on the capacitance values. This characteristic influences the circuit's behaviour and must be considered when designing complex electronic systems. Uneven voltage distribution can affect the entire system's performance, making choosing caps with appropriate capacitance values and voltage ratings for a specific application is vital.

Another important factor to consider is the plate area. In general, caps with larger plate areas have higher capacitance values. Therefore, when connecting capacitors in series, it is essential to evaluate how the plate area of each capacitor influences the overall capacitance of the series connection. Understanding these factors will enable engineers and hobbyists to make informed decisions when designing and constructing electronic circuits.

Capacitors in series are versatile and valuable configurations for various electronic applications. By understanding the principles of capacitance, voltage distribution, energy storage, and the influence of dielectric materials, one can harness the full potential of capacitors connected in series. Additionally, being mindful of the advantages and disadvantages of this configuration and considering the compatibility of different capacitor types and values will enable the creation of efficient, reliable, and effective electronic circuits. As electronics evolve, they will remain critical in developing innovative devices and systems. A solid foundation in Basic Electricity makes it easier to grasp why capacitors in series lower overall capacitance but increase voltage handling.

Related Articles