Electricity generation is the process of producing electric power from various energy sources, including fossil fuels, solar, wind, hydro, and nuclear. It uses turbines and generators to convert mechanical or thermal energy into electrical energy for residential, commercial, and industrial use.

What is Electricity Generation?

Electricity generation is a process that involves producing electrical power from various sources.

✅ Converts mechanical, thermal, or chemical energy into electrical power

✅ Uses generators powered by steam, wind, water, or combustion

✅ Essential for powering homes, industries, and transportation

In the United States, power production from utility-scale generators was about 4.1 trillion kilowatt-hours (kWh) in 2019. Fossil fuels, including coal, natural gas, and petroleum, produced about 63% of the electricity, while nuclear energy produced around 20%. The remaining 17% was generated from renewable energy sources, including solar photovoltaics, wind turbines, and hydroelectric power production. To explore the full process from fuel to flow, see our detailed guide on how electricity is generated.

Electricity Generation Sources Compared

| Energy Source |

How It Generates Electricity |

Global Usage (approx.) |

Carbon Emissions |

Renewable? |

| Coal |

Burns to heat water → steam → turbine spins generator |

35% |

High |

No |

| Natural Gas |

Combusts to drive turbines directly or via steam |

23% |

Moderate |

No |

| Nuclear |

Nuclear fission heats water → steam → turbine |

10% |

Low |

No (but low-carbon) |

| Hydropower |

Flowing water spins turbines |

15% |

Very Low |

Yes |

| Wind |

Wind turns large blades connected to a generator |

7% |

Zero |

Yes |

| Solar PV |

Converts sunlight directly into electricity via photovoltaic cells |

5% |

Zero |

Yes |

| Geothermal |

Uses Earth’s internal heat to create steam and turn turbines |

<1% |

Very Low |

Yes |

| Biomass |

Burns organic material to generate heat for steam turbines |

~1.5% |

Moderate (depends on fuel) |

Partially |

Hydroelectric Power Generation

Hydroelectric power production units utilize flowing water to spin a turbine connected to a generator. Falling water systems accumulate water in reservoirs created by dams, which then release it through conduits to apply pressure against the turbine blades, driving the generator. In a run-of-the-river system, the force of the river current applies pressure to the turbine blades to produce power. In 2000, hydroelectric generation accounted for the fourth-largest share (7 percent) of electricity production, at 273 billion kWh. Explore how water and electricity interact in hydroelectric plants, where falling water is converted into renewable energy.

Non-Hydro Renewable Energy Sources in Electricity Generation

Non-water renewable sources, including geothermal, refuse, waste heat, waste steam, solar thermal power plants, wind, and wood, contribute only small amounts (about 2 percent) to total power production. In 2019, power production from these sources totalled 84 billion kWh. The entire electric power industry production in 2019 was 3,800 billion kWh, with utilities' net production accounting for 3,015 billion kWh and net generation by non-utility power producers 785 billion kWh.

U.S. Electricity Generation by Energy Source: Trends and Shifts

The United States' share of electrical energy production from different sources has changed more rapidly since 2007 than ever since 1950. On the other hand, Canada's energy production is significantly less than that of the USA, primarily in Ontario and British Columbia. At least three trends are catalyzing these changes: (1) the low price of natural gas; (2) the rise in renewable and distributed generation due to falling costs; and (3) recent Federal and State policies impacting production. There are many innovative ways to generate electricity, from traditional fossil fuels to cutting-edge renewable technologies.

Fuel Source Diversity in U.S. and Canadian Electricity Production

Diversity is a key attribute in U.S. and Canadian electricity production. However, rather than being the result of a deliberative, long-term national initiative, this diversity has developed through spurts of growth in specific production technologies at different times. This is often due to policies, historical events, capital costs, fuel costs, and technological advancements.

Historical Growth of Electricity Generation by Energy Source

Most energy sources have experienced eras of significant capacity growth in terms of terawatt hours: hydro (1930‒1950, not shown); coal (1950-1985); nuclear (1960‒1980); natural gas (1990‒2010); and renewables (2005‒present). Nuclear energy is increasingly recognized as a key solution for achieving carbon reduction goals—learn how it contributes to net-zero emissions.

Changing U.S. Power Generation Mix: Centralized to Distributed Energy

The U.S. generation mix has undergone significant changes over the past few decades and is projected to continue evolving substantially. The U.S. generation fleet is transitioning from one dominated by centralized generators with high inertia and dispatchability to one more hybridized, relying on a mixture of traditional, centralized production and variable utility-scale and distributed renewable energy production.

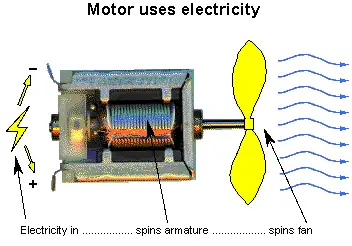

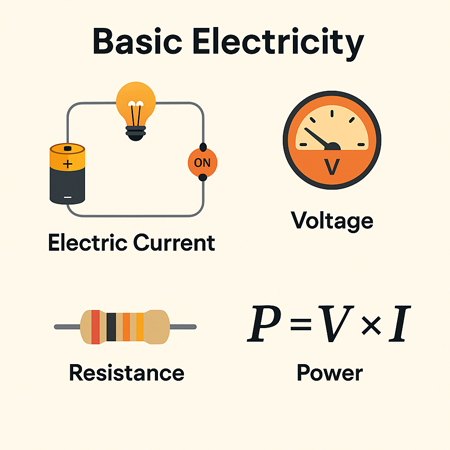

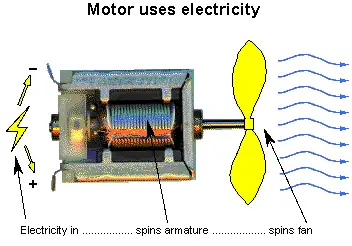

Power Generation Technologies: From Diesel Engines to Wind Turbines

To generate power, various sources are utilized, including diesel engines, gas turbines, and nuclear power plants. Fossil fuels, including natural gas and coal, are burned to create hot gases that go through turbines, which spin the copper armature inside the generator and generate an electric current. In a nuclear power plant, nuclear reactions generate heat that is used to heat water, which then turns into steam and passes through a turbine to produce electricity. In a wind turbine, the wind pushes against the turbine blades, causing the rotor to spin and generating an electric current. In a hydroelectric turbine, flowing or falling water pushes against the turbine blades, causing the rotor to spin and generating an electric current. As the global energy landscape evolves, many experts are re-evaluating the role of nuclear power—learn more in our feature on the future of nuclear energy.

Electricity Generation by Utilities and Non-Utility Power Producers

To meet these immediate demands, utilities and nonutility power producers operate several electric generating units powered by various fuel sources. Renewable fuels, such as water, geothermal, wind, and other renewable energy sources like solar photovoltaics, are used as sources of power, alongside fossil fuels and uranium.

Fossil Fuel Electricity Generation: Coal, Natural Gas, and Petroleum

Coal was the fuel used to generate the largest share (51.8 percent) of electricity in 2000, with natural gas and petroleum accounting for 16.1 percent and 3 percent, respectively. Steam-electric generating units burn fossil fuels, such as coal, natural gas, and petroleum, to produce steam. This steam is then used to turn a turbine into a generator, producing power. On the other hand, gas turbine generators burn fuels to create hot gases, which also go through a turbine, spinning the copper armature inside the generator and generating an electric current. Diesel engine generators are also used, where the combustion occurs inside the engine's cylinders, which are connected to the generator's shaft. The mechanical energy provided by the turbine drives the generator, which in turn produces energy.

Electricity Generation Trends and the Global Shift Toward Renewables

The production of electrical energy has experienced various eras of significant capacity growth in the United States, Canada, and other countries worldwide. The future of power production is transitioning to a more hybridized generation fleet that relies on a combination of traditional, centralized power production and variable utility-scale and distributed renewable energy sources. Low natural gas prices drive this transition, the rise of renewable and distributed energy sources, and recent Federal and State policies that impact generation. Discover the most common renewable energy sources powering the shift toward a cleaner, more sustainable electricity future.

Enhance your expertise in clean energy with our comprehensive Renewable Energy Grid Integration Training course. Designed for electrical professionals, this course covers the challenges and solutions associated with connecting solar, wind, and other renewable energy sources to the power grid. Stay ahead of industry trends, improve system reliability, and gain valuable skills to support the transition to a sustainable energy future. Enroll today and take the next step in your professional development.

Frequently Asked Questions

How is electricity generated from renewable energy sources?

Electricity is generated from renewable energy sources by converting the energy of the sun, wind, water, or earth into electrical energy. For example, solar photovoltaic panels generate power directly from sunlight, wind turbines to generate electricity from wind energy, and hydroelectric power plants generate power from falling water.

What are the different types of fossil fuels used?

The different types of fossil fuels used include coal, natural gas, and petroleum. Coal is the most commonly used fossil fuel for energy production, followed by natural gas and oil.

What are the advantages and disadvantages of using nuclear power plants for electricity generation?

Advantages of using nuclear power plants include that they produce a large amount of energy with a low amount of fuel, emit less carbon dioxide than fossil fuel power plants, and are not dependent on weather conditions like wind or solar power. Disadvantages include the risks associated with nuclear accidents, the high cost of building and maintaining nuclear power plants, and the long-term storage of nuclear waste.

How do gas turbines work to generate electricity?

Gas turbines burn natural gas or other fuels to heat air, which expands and drives the turbine. Finally, the turbine is connected to a generator that converts the mechanical energy of the turbine into electrical energy.

What is the role of steam turbines in electricity generation?

Steam turbines are commonly used to convert thermal energy from steam into mechanical energy that drives a generator. Steam is produced by burning fossil fuels or using heat from nuclear reactions or geothermal sources. The steam drives the turbine blades, which are connected to the generator to produce electricity.

What are some examples of non-renewable energy sources?

Examples of non-renewable energy sources used for power production include fossil fuels, such as coal, natural gas, and petroleum, as well as nuclear energy.

How is electricity generated and distributed in the United States?

Various power plants, including those powered by fossil fuels, nuclear energy, and renewable energy sources, generate electricity in the United States. Electric power is transported over a complex network of power lines and transformers to homes, businesses, and other consumers through local utility companies. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) and various state regulatory agencies regulate power distribution.

Related Articles

_1497153600.webp)