Watthour Meter Explained

A watthour meter measures electrical energy consumption in kilowatt-hours (kWh) for residential, commercial, and industrial applications, ensuring accurate billing, energy management, and compliance with utility standards.

What is a Watthour Meter?

✅ Measures total electrical energy in kilowatt-hours (kWh) over time

✅ Supports accurate billing, energy monitoring, and demand analysis

✅ Used in residential, commercial, and industrial revenue metering

Advancements in Watthour Meter Technology and Energy Measurement

Watthour meter technology plays a crucial role in modern electrical engineering and maintenance by providing accurate measurement and monitoring of energy consumption. These devices are indispensable for managing energy efficiency, optimizing power distribution, and ensuring compliance with regulatory standards. For electrical professionals, understanding how they operate and are maintained is essential to minimize energy losses and enhance the reliability of electrical systems. With the growing demand for precise energy data in both residential and industrial applications, staying informed about advancements in watthour meter technology is more important than ever. Understanding how a watthour is calculated helps clarify how a watthour meter tracks total energy usage for accurate billing.

Your electric utility is not too interested in how much power you're consuming for one appliance or even how much power a single household is drawing at any given time. By far the greater concern is the total energy that is used over a day, a week, a month or a year. Electrical energy is measured in watt-hours or, more commonly for utility purposes, in kilowatt-hours (kWh). The device that measures this consumption is the watt-hour meter or kilowatt-hour meter. For a deeper understanding of the units used in metering, see our guide on electrical energy and how it is measured in kilowatt-hours.

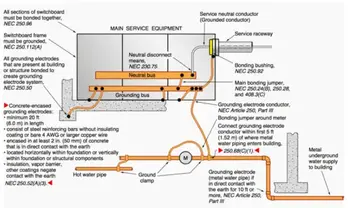

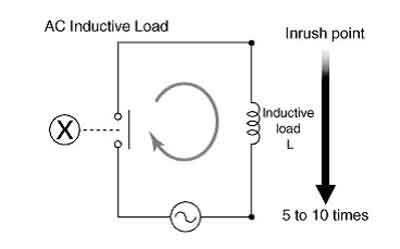

The most common method for measuring electrical energy is by using a small electric motor device, whose speed depends on the current, and thereby on the power at a constant voltage. The number of turns of the motor shaft, in a given length of time, is directly proportional to the number of watt hours consumed. The motor is placed at the point where the utility wires enter the house, apartment or building. This is usually at a point where the voltage is 234 V. This is split into some circuits with 234 V, for heavy-duty appliances such as the oven, washer and dryer, and the general household circuits for lamps, clock radios and television sets. The principles behind watthour meters are closely tied to basic electricity and the relationship between active power and time.

Understanding the Spinning Disk in Electromechanical Watthour Meters

You've surely seen the little disk in the utility meter going around and around, sometimes fast, other times slowly. Its speed depends on the power you're using. The total number of turns of this little disk, every month, determines the size of the bill you will get, as a function also, of course, of the cost per kilowatt hour for electricity.

Kilo-watt-hour meters count the number of disk turns by means of geared, rotary drums or pointers. The drum-type meter gives a direct digital readout. The pointer type has several scales calibrated from 0 to 9 in circles, some going clockwise and others going counterclockwise. Mechanical and electronic meters both rely on the concepts of electrical resistance and current to provide precise readings.

How to Read a Pointer-Type Watthour Meter Accurately

Reading a pointer-type utility meter is a little tricky because you must think in whatever direction (clockwise or counterclockwise) the scale goes. An example of a pointer-type utility meter is shown in Fig. 3-11. Read from left to right. For each little meter, take down the number that the pointer has most recently passed. Write down the rest as you go. The meter in the figure reads 3875 kWh. If you want to be really precise, you can say it reads 3875-1/2 kWh. To place watt hour metering in historical context, explore our history of electricity page and learn how early meters evolved into today’s advanced devices.

Fig. 3-11 An example of a utility kilo-watthour meter. The reading is a little more than 3875 kWh.

Related Articles

_1497175164.webp)