What do Ammeters Measure?

An ammeter measures electric current in a circuit, displayed in amperes (A). Connected in series with low internal resistance to reduce burden voltage, it ensures accurate readings for testing, fault detection, and diagnostics.

What do Ammeters Measure?

Ammeters are measuring devices that measure the flow of electricity in the form of current in a circuit.

✅ Measure electric current in amperes, connected in series with low internal resistance to minimize burden voltage.

✅ Available in analog, digital, clamp, and current transformer designs.

✅ Used for testing, fault detection, continuity checks, and diagnostics.

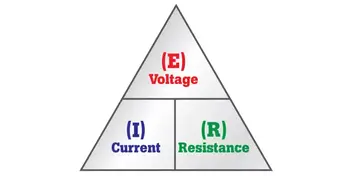

Electrical currents are then measured in the form of amperes, hence the name "ammeter". The term "ammeter" is sometimes used incorrectly as "ampmeter". Understanding how an ammeter works is easier when you first explore the basics of electricity fundamentals, including how voltage, current, and resistance interact in a circuit.

An ammeter measures electric current in a circuit, expressed in amperes (A). It must be connected in series with the load so that all the current flows through it, and is designed with low internal resistance to minimize burden voltage, thereby ensuring accurate readings without significantly affecting the circuit’s performance. The measurement unit for an ammeter is the ampere, explained in detail on our what is an ampere page, which also covers its relationship to other electrical units.

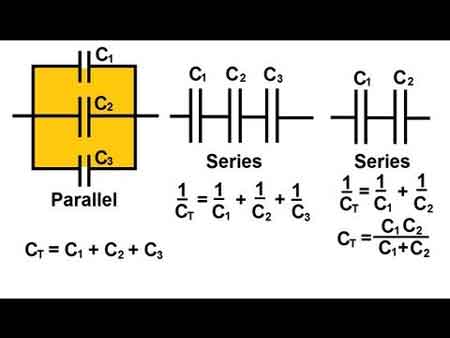

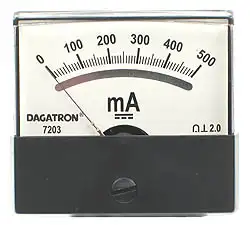

Ammeters are designed (as well as ohmmeters and voltmeters) to be used with a sensitive current detector such as a moving coil in a galvanometer. To measure the electric current flow through it, an ammeter is placed in series with a circuit element. The ammeter is designed to offer very low resistance to the current, so that it does not appreciably change the circuit it is measuring. To do this, a small resistor is placed in parallel with the galvanometer to shunt most of the current around the galvanometer. Its value is chosen so that when the design current flows through the meter, it will deflect to its full-scale reading. A galvanometer's full-scale current is very small: on the order of milliamperes. To see how ammeters fit into broader measurement tools, check out our guide on what is a voltmeter and what is a multimeter, which measure multiple electrical properties.

An Ammeter is analog. It is not mechanical or digital. It uses an analog-to-digital converter (ADC) to measure the voltage across the shunt resistor. The ADC is read by a microcomputer that performs the calculations to display the current through the resistor.

How an Ammeter Works

An ammeter works by being placed in series with the circuit so that all the current flows through it. Inside, a shunt resistor with very low internal resistance creates a small, measurable voltage drop proportional to the current. In analog designs, this current is partly diverted around a sensitive moving-coil mechanism, which displays the reading on a scale. In digital designs, the voltage drop across the shunt is measured by an analog-to-digital converter (ADC) and calculated into an amperes value, ensuring accurate measurement without significantly disturbing the circuit’s performance. Accurate current measurement also depends on understanding what is electrical resistance and how it affects current flow, especially in low-resistance ammeter designs.

Types and Mechanisms

Analog ammeter – Includes moving-coil (D'Arsonval) and moving-iron types, which use magnetic deflection to display current on a scale. These designs are valued for their simplicity, durability, and ability to provide continuous current readings.

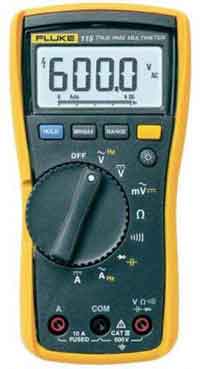

Digital ammeter – Uses a shunt resistor to create a small voltage drop proportional to the current. This voltage is measured by an analog-to-digital converter (ADC) and displayed as a precise digital value. Digital ammeters often feature higher accuracy, wider measurement ranges, and additional functions such as data logging.

Clamp meter – Measures current without breaking the circuit by detecting the magnetic field around a conductor. This method is ideal for quick testing, especially in high-current applications or where live connections cannot be interrupted.

Current transformer (CT) ammeter – Designed for high-current AC systems, this type uses a transformer to scale down large primary currents into a safe, measurable secondary current for the meter.

Shunts and Operation

A shunt resistor is a precision, low-resistance component used in many ammeters. In analog designs, it is placed in parallel with the meter movement, diverting most of the current to protect the instrument. In certain digital designs, it is placed in series with the circuit. By measuring the voltage drop across the shunt and applying Ohm’s law, the meter accurately calculates the current. This approach allows for measurement of very large currents without damaging the meter and helps maintain measurement stability.

Applications and Value

Ammeters are essential tools in electrical testing, short-circuit detection, continuity testing, and system diagnostics. They help identify overloads, open circuits, and unstable current conditions that may indicate equipment faults or inefficiencies.

In industrial, commercial, and residential settings, ammeters are used for equipment maintenance, troubleshooting, and performance monitoring. Specialized variants such as milliammeters and microammeters are designed for extremely low current measurements, while integrating ammeters track current over time to determine total electrical charge delivered to a device or system. For historical context on the development of measuring instruments, visit our history of electricity page to learn how electrical science evolved over time.

Practical Applications of Ammeters

Ammeters are used in a wide range of electrical and electronic work:

-

Automotive diagnostics – Measuring current draw from the battery to detect parasitic drains, starter motor issues, and charging system faults.

-

Solar panel and battery monitoring – Tracking current output from photovoltaic arrays and the charging/discharging rates of storage batteries to optimize system efficiency.

-

Industrial motor maintenance – Monitoring motor current to identify overload conditions, detect bearing wear, or confirm correct load operation.

-

Household appliance servicing – Checking current draw to troubleshoot faulty components or ensure devices operate within safe limits.

-

Power distribution systems – Ensuring current levels remain within capacity for cables, fuses, and protective devices.