What is Voltage?

By Harold WIlliams, Associate Editor

Voltage is the electrical potential difference between two points, providing the force that moves current through conductors. It expresses energy per charge, powering devices, controlling circuits, and ensuring efficient and safe operation of electrical and electronic systems.

What is Voltage?

Voltage is the electric potential difference, the work done per unit charge (Joules per Coulomb). It:

✅ Is the difference in electric potential energy between two points in a circuit.

✅ Represents the force that pushes electric current through conductors.

✅ It is measured in volts (V), and it is essential for power distribution and electrical safety.

To comprehend the concept of what is voltage, it is essential to understand its fundamental principles. Analogies make this invisible force easier to picture. One of the most common is the water pressure analogy: just as higher water pressure pushes water through pipes more forcefully, higher voltage pushes electric charges through a circuit. A strong grasp of voltage begins with the fundamentals of electricity fundamentals, which explain how current, resistance, and power interact in circuits.

Another way to imagine what is voltage is as a hill of potential energy. A ball placed at the top of a hill naturally rolls downward under gravity. The steeper the hill, the more energy is available to move the ball. Likewise, a higher voltage means more energy is available per charge to move electrons in a circuit.

A third analogy is the pump in a water system. A pump creates pressure, forcing water to move through pipes. Similarly, a battery or generator functions as an electrical pump, supplying the energy that drives electrons through conductors. Without this push, charges would remain in place and no current would flow.

Together, these analogies—water pressure, potential energy hill, and pump—show how voltage acts as the essential driving force, the “electrical pressure” that enables circuits to function and devices to operate. Since voltage and Current are inseparable, Ohm’s Law shows how resistance influences the flow of electricity in every system.

These analogies help us visualize voltage as pressure or stored energy, but in physics, voltage has a precise definition. It is the work done per unit charge to move an electric charge from one point to another. Mathematically, this is expressed as:

V = W / q

where V is voltage (in volts), W is the work or energy (in joules), and q is the charge (in coulombs). This equation shows that one volt equals one joule of energy per coulomb of charge.

In circuit analysis, voltage is also described through Ohm’s Law, which relates it to current and resistance:

V = I × R

where I is current (in amperes) and R is resistance (in ohms). This simple but powerful formula explains how voltage, current, and resistance interact in every electrical system.

Italian physicist Alessandro Volta played a crucial role in discovering and understanding V. The unit of voltage, the volt (V), is named in his honor. V is measured in volts, and the process of measuring V typically involves a device called a voltmeter. In an electrical circuit, the V difference between two points determines the energy required to move a charge, specifically one coulomb of charge, between those points. The history of voltage is closely tied to the History of Electricity, where discoveries by pioneers like Volta and Franklin have shaped modern science.

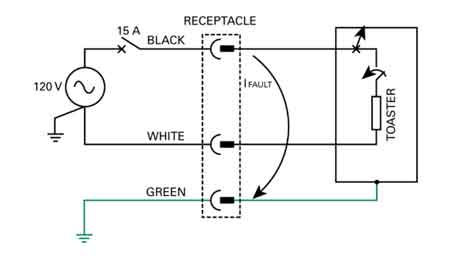

An electric potential difference between two points produces an electric field, represented by electric lines of flux (Fig. 1). There is always a pole that is relatively positive, with fewer electrons, and one that is relatively negative, with more electrons. The positive pole does not necessarily have a deficiency of electrons compared with neutral objects, and the negative pole might not have a surplus of electrons compared with neutral objects. But there's always a difference in charge between the two poles. So the negative pole always has more electrons than the positive pole.

Fig 1. Electric lines of flux always exist near poles of electric charge.

The abbreviation for voltage measurement is V. Sometimes, smaller units are used. For example, the millivolt (mV) is equal to a thousandth (0.001) of a volt. The microvolt (uV) is equal to a millionth (0.000001) of a volt. And it is sometimes necessary to use units much larger than one volt. For example, one kilovolt (kV) is equal to one thousand volts (1,000). One megavolt (MV) is equal to one million volts (1,000,000) or one thousand kilovolts. When comparing supply types, the distinction between Direct Current and AC vs DC shows why standardized voltage systems are essential worldwide.

The concept of what is voltage is closely related to electromotive force (EMF), which is the energy source that drives electrons to flow through a circuit. A chemical battery is a common example of a voltage source that generates EMF. The negatively charged electrons in the battery are compelled to move toward the positive terminal, creating an electric current.

In power distribution, three-phase electricity and 3 Phase Power demonstrate how higher voltages improve efficiency and reliability.

Voltage is a fundamental concept in electrical and electronic systems, as it influences the behavior of circuits and devices. One of the most important relationships involving V is Ohm's Law, which describes the connection between voltage, current, and resistance in an electrical circuit. For example, Ohm's Law states that the V across a resistor is equal to the product of the current flowing through it and the resistance of the resistor.

The voltage dropped across components in a circuit is critical when designing or analyzing electrical systems. Voltage drop occurs when the circuit components, such as resistors, capacitors, and inductors, partially consume the V source's energy. This phenomenon is a crucial aspect of circuit analysis, as it helps determine a system's power distribution and efficiency. Potential energy is defined as the work required to move a unit of charge from different points in an electric dc circuit in a static electric field. Engineers often analyze Voltage Drop to evaluate circuit performance, alongside concepts like Electrical Resistance.

Voltage levels are standardized in both household and industrial applications to ensure the safe and efficient operation of electrical equipment. In residential settings, common voltage levels range from 110 to 240 volts, depending on the country. Industrial applications often utilize higher voltages, ranging from several kilovolts to tens of kilovolts, to transmit electrical energy over long distances with minimal losses.

Another important distinction in the realm of voltage is the difference between alternating current (AC) and direct current (DC). AC alternates periodically, whereas DC maintains a constant direction. AC is the standard for most household and industrial applications, as it can be easily transformed to different voltage levels and is more efficient for long-distance transmission. DC voltage, on the other hand, is often used in batteries and electronic devices.

Voltage is the driving force behind the flow of charge carriers in electrical circuits. It is essential for understanding the behavior of circuits and the relationship between voltage, current, and resistance, as described by Ohm's Law. The importance of V levels in household and industrial applications, as well as the significance of voltage drop in circuit analysis, cannot be overstated. Finally, the distinction between AC and DC voltage is critical for the safe and efficient operation of electrical systems in various contexts.

By incorporating these concepts into our understanding of voltage, we gain valuable insight into the world of electricity and electronics. From the pioneering work of Alessandro Volta to the modern applications of voltage in our daily lives, it is clear that voltage will continue to play a crucial role in the development and advancement of technology. Foundational principles such as Amperes Law and the Biot Savart Law complement voltage by describing how currents and magnetic fields interact.