Low voltage refers to electrical systems operating at 50 to 1000 volts AC or 120 to 1500 volts DC. Common in residential, commercial, and control circuits, it reduces shock risks while powering lighting, HVAC, security systems, and automation equipment safely.

What is Low Voltage?

Low voltage is a range of electrical power levels below high-voltage thresholds.

✅ Reduces risk of electrical shock in residential and commercial settings

✅ Powers lighting, security, HVAC, and control systems

✅ Common in telecommunications and automation applications

In today's technologically driven world, understanding the concept of low voltage (LV) is essential. Low voltage systems are widely used across industries, homes, and offices, making them an integral part of our daily lives. This article provides an overview of LV, its applications, safety measures, and regulations, incorporating the keywords provided. Low voltage systems are designed to operate below 600 volts, unlike high voltage systems that present increased shock hazards.

The low voltage definition is relatively simple: Any electrical system or equipment operating at a voltage level less than or equal to 600 volts. LV systems in the United States are generally categorized as those working between 50 and 600 volts. These systems are utilized in various applications due to their low power consumption and reduced risk of electric shock. Understanding the concept of voltage is essential when working with residential or industrial low voltage wiring.

Applications

Low voltage applications are diverse and include control rooms, distribution systems, lighting, communication systems, and security systems. LV wiring is often used in these applications, as it is designed for smaller currents and offers increased safety compared to regular wiring. This wiring type is also more cost-effective and easier to install. Voltage drop can significantly impact the performance of low voltage circuits, especially over long wiring runs.

Regarding LV safety, it is crucial to take necessary precautions as even LV electrical equipment can pose risks. For example, to minimize the chance of electric shock, one should always turn off the power supply before working on any electrical equipment and use insulated tools. Additionally, it is essential to adhere to local LV regulations and standards to ensure a safe working environment.

Devices

Low voltage devices are found in various settings, from residential to commercial and industrial. Some examples of low voltage devices include thermostats, doorbells, intercom systems, and landscape lighting. These devices usually require transformers to convert the higher voltage from the main power supply to a lower voltage suitable for operation.

Regulations and standards for LV installations vary by country and region. However, the National Electrical Code (NEC) provides guidelines and requirements for LV installations to ensure safety and reliability in the United States. Professionals working with low voltage systems must adhere to these guidelines and any additional local regulations.

Low voltage transformers and power supplies are critical in distributing low voltage electricity. Transformers are used to step down higher voltages from the main power supply to the required LV level. In contrast, power supplies regulate and distribute electrical energy to various devices. Low voltage distribution systems are designed to efficiently deliver electricity to low voltage equipment while maintaining safety and reliability.

Systems

While low voltage systems are generally safer than high voltage electrical systems, they still require proper handling and adherence to safety measures. High-voltage transmission systems are used to transport electricity over long distances from power plants to substations. High voltages range from 100 kV to 765 kV, while ultra-high voltages can reach above 800 kV. Large industrial facilities, such as factories that use medium-voltage systems, typically operate between 1 kV and 35 kV.

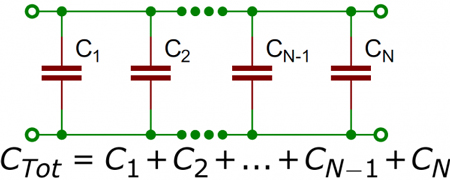

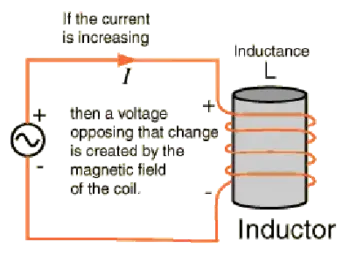

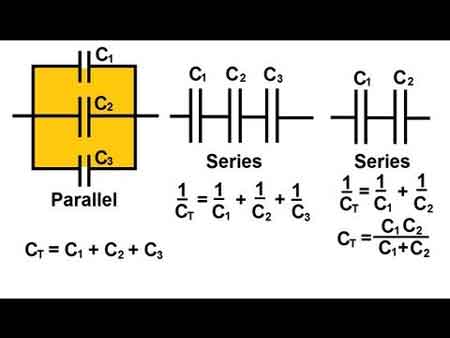

Understanding LV is crucial today, as these systems are widely used in various applications. With proper installation, adherence to regulations, and safety precautions, LV systems can provide numerous devices with an efficient and reliable power supply. As a result, low voltage systems play an essential role in our daily lives, whether for lighting, communication, or security. Key electrical components such as resistors and capacitors are frequently used in low voltage control systems.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is "low voltage" defined differently in 110V systems and 220V systems?

While the term "low voltage" describes electrical systems operating at a voltage level lower than a certain threshold, the specific voltage ranges considered low voltage can vary slightly between countries and regions due to differences in their electrical distribution systems. However, the general concept remains the same across 110V systems in North America and 220V systems in the EU. For efficient power distribution, low voltage systems rely on solid grounding practices, making ground faults and electrical faults important safety considerations.

In North America, low voltage typically refers to electrical systems operating between 50 and 600 volts. In contrast, in the EU, the term "LV" is defined by the Low Voltage Directive (LVD), which covers electrical equipment designed for use with a voltage rating of 50 to 1000 volts for alternating current (AC) and 75 to 1500 volts for direct current (DC).

Despite these minor differences in the defined voltage ranges, the reasons behind the classification of LV systems remain consistent. LV systems are generally considered safer than their high voltage counterparts, as the risk of electric shock is lower. Additionally, they consume less power, making them more energy-efficient and cost-effective for certain applications.

The main factor causing the difference in voltage levels between regions is the choice of electrical distribution systems. For example, 110-120V systems are more common in North America, while in Europe and many other parts of the world, 220-240V systems are standard. This difference is primarily due to historical reasons and the evolution of each region's electrical infrastructure over time.

Regardless of these regional differences in voltage levels, the fundamental principles and safety considerations for LV systems remain largely the same. Both 110V and 220V systems use LV electrical equipment and wiring to provide power for various applications while adhering to regional safety standards and regulations to ensure these systems' safe and efficient operation. The behavior of current in low voltage applications is best understood by applying Ohm’s Law, which explains the relationship between voltage, current, and resistance.

What are examples of low voltage systems?

Low voltage systems are widely used in various residential, commercial, and industrial applications due to their increased safety and energy efficiency. Here are some examples of LV systems:

Lighting systems: Low voltage lighting, such as LED lights and halogen lamps, is commonly used for residential and commercial purposes, including landscape lighting, recessed lighting, and track lighting. These systems often use transformers to step down the voltage from the main power supply to a suitable level for the lights.

Security systems: LV is used in security systems, including alarm systems, access control systems, and surveillance cameras. These systems require a stable and reliable power source with minimal risk of electrical hazards.

Communication systems: LV wiring is utilized in various communication systems, including intercoms, telephone lines, and data networks. It enables the reliable transmission of data and voice signals while minimizing energy consumption and interference.

Audio and video systems: LV components are used in home theatre systems, speakers, and AV equipment. The low voltage wiring ensures minimal signal loss and interference for better audio and video quality.

HVAC controls: Thermostats, sensors, and control panels for heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems often use low voltage wiring and components to maintain efficient energy use and reliable control of the HVAC system.

Doorbells and chimes: LV systems are commonly used in doorbells and chime systems to ensure safe and reliable operation.

Fire alarm systems utilize LV wiring and components to provide a reliable means of detecting and responding to potential fire hazards while minimizing the risk of electrical hazards.

Home automation systems often utilize LV for controlling and automating various devices, including lighting, appliances, and security systems. This allows for the energy-efficient and safe operation of connected devices.

Solar power systems: In small-scale solar power installations, LV DC systems are used to store and distribute the electricity generated by solar panels. These systems typically include charge controllers, batteries, and inverters to efficiently manage the power supply.

Industrial control systems: LV is used in various industrial applications to control and monitor machinery and equipment. This includes programmable logic controllers (PLCs), motor controls, and sensor networks, which require stable and reliable power sources with minimal risk of electrical hazards. Devices like multimeters and voltmeters are essential tools for testing and maintaining low voltage installations.

Related Articles