An electrical circuit is a closed loop that allows electric current to flow through conductors, power sources, and loads. Circuits connect electrical devices, enable energy transfer, and ensure safe operation in homes, industries, and power systems.

What is an Electrical Circuit?

An electrical circuit is a path through which electricity flows from a power source to one or more devices that are connected.

✅ Provides controlled current flow through conductors

✅ Powers electrical devices safely and efficiently

✅ Includes sources, loads, and protective components

Gaining a grasp of the basic electricity of electrical circuits, including series and parallel configurations, voltage, current, resistance, Ohm's Law, and circuit analysis techniques, is vital for anyone interested in electronics, electrical engineering, or the inner workings of modern technology.

Core Components & Function

In order to understand what an electrical circuit is, one must appreciate that,

At its core, an electrical circuit is a closed loop or pathway that facilitates the flow of electric current. This concept is essential in electronics and electrical engineering, as it provides the basis for the operation of everyday items, including smartphones, computers, and home appliances.

Within an electrical circuit, components are connected via conductive materials, such as wires, which enable the movement of electrons from a power source to other components and back.

The primary components of an electrical circuit include a power source (e.g., a battery or power supply unit), conductive materials (typically wires), a load (such as a resistor, motor, or light bulb), and a control element (for example, a switch). The power source supplies the voltage necessary for electric current flow, while the load transforms electrical energy into other forms, such as light or heat. Meanwhile, the control element permits the user to initiate or halt the flow of electrons, effectively turning a device on or off.

-

For students, a simple example is a battery connected to an LED, which demonstrates how electricity creates light.

-

For professionals, an industrial motor powered by a control circuit shows how electrical energy drives large-scale equipment.

Circuit Types (Series vs. Parallel)

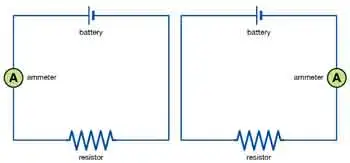

Electrical circuits can be classified into three main types: series, parallel, and combination circuits.

-

Series circuits connect components end-to-end, allowing current to flow sequentially through each one. Example: holiday string lights, where a single bulb outage can disrupt the entire circuit.

-

Parallel circuits enable current to flow through multiple paths. Example: household wiring, where turning off one light doesn’t affect others.

-

Combination circuits mix both series and parallel configurations to handle more complex systems.

Fundamental Laws (Ohm’s Law, Kirchhoff’s Laws)

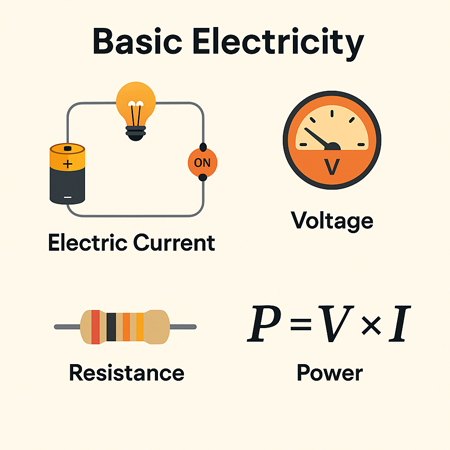

A fundamental understanding of voltage, current, and resistance is crucial for comprehending electrical circuit operations.

Voltage, the driving force that propels electric charge through a circuit, and current, the flow of electric charge measured in amperes (A), are closely related to resistance. Resistance, expressed in ohms (Ω), represents the opposition to the flow of current. These elements are interconnected through Ohm's law, which states that the voltage across a conductor is directly proportional to the current it carries and inversely proportional to its resistance: V = IR, where V represents voltage, I denotes current, and R represents resistance. Understanding how current creates magnetic fields is explained by Ampere's Law, which forms the basis for analyzing electromagnetism in electrical circuits.

Circuit analysis determines the current, voltage, and power associated with each component in an electrical circuit. Techniques such as Kirchhoff's Law of voltage and current, Thevenin's theorem, and Norton's theorem are employed to analyze and resolve electrical circuit issues. These methods enable engineers to design and troubleshoot electronic devices and systems effectively.

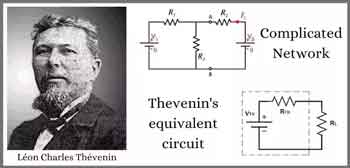

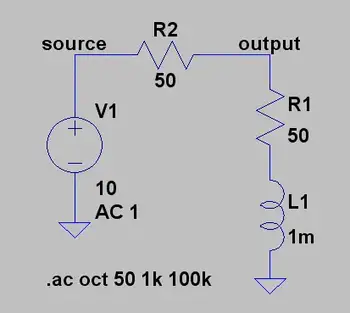

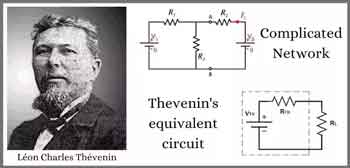

Thevenin's Theorem

Thevenin's theorem is a fundamental principle in electrical engineering and circuit analysis. It is a powerful technique to simplify complex linear circuits, making it easier to analyze and calculate the current, voltage, and power across specific components. The theorem is named after the French engineer Charles Léonard Siméon Thévenin, who proposed it in 1883.

Thevenin's theorem states that any linear, active, bilateral network containing voltage sources, current sources, and resistors can be replaced by an equivalent circuit consisting of a single voltage source (called Thevenin's voltage, Vth) in series with a single resistor (called Thevenin's resistance, Rth) connected to the terminals of the original circuit. This simplified circuit, known as the Thevenin equivalent circuit, can then be used to analyze the behaviour of the original circuit with a specific load connected to its terminals.

Steps to apply Thevenin’s theorem:

-

Identify the portion of the circuit you want to simplify and the terminals where the load will be connected.

-

Remove the load from the terminals (if present) and leave the terminals open-circuited.

-

Calculate the open-circuit voltage across the terminals. This value is Thevenin's voltage (Vth).

-

Calculate the equivalent resistance seen from the open-circuited terminals with all independent voltage sources replaced by short circuits (zero resistance) and all independent current sources replaced by open circuits (infinite resistance). This value is Thevenin's resistance (Rth).

-

Create the Thevenin equivalent circuit using the calculated Vth and Rth values, then connect the original load across the terminals.

Once the Thevenin equivalent circuit is determined, you can easily analyze the circuit's behaviour and calculate the current through the load, the voltage across the load, or even the power delivered to the load. This technique is particularly useful when analyzing circuits with varying loads or examining the circuit's behaviour at multiple points, as it simplifies calculations and saves time.

Norton’s Theorem

Norton's theorem is a fundamental principle in electrical engineering and circuit analysis that simplifies the analysis of complex linear circuits. Named after the American engineer Edward Lawry Norton, who introduced it in the early 20th century, the theorem is a counterpart to Thevenin's theorem.

While Thevenin's theorem reduces a complex network to an equivalent voltage source in series with a resistor, Norton's theorem simplifies the network to an equivalent current source parallel to a resistor.

Norton's theorem states that any linear, active, bilateral network containing voltage sources, current sources, and resistors can be replaced by an equivalent circuit consisting of a single current source (called Norton's current, IN) in parallel with a single resistor (called Norton's resistance, RN) connected to the terminals of the original circuit.

Steps to apply Norton’s theorem:

-

Identify the portion of the circuit you want to simplify and the terminals where the load will be connected.

-

Remove the load from the terminals (if present) and leave the terminals open-circuited.

-

Calculate the short-circuit current flowing between the terminals. This value is Norton's current (IN).

-

Calculate the equivalent resistance seen from the open-circuited terminals with all independent voltage sources replaced by short circuits (zero resistance) and all independent current sources replaced by open circuits (infinite resistance). This value is Norton's resistance (RN). Note that Norton's resistance is equal to Thevenin's, as both are calculated similarly.

-

Create the Norton equivalent circuit with the calculated IN and RN values, connecting the original load across the terminals.

Once the Norton equivalent circuit is established, you can easily analyze the circuit's behaviour and calculate the current through the load, the voltage across the load, or even the power delivered to the load. Like Thevenin's theorem, Norton's theorem is particularly useful when dealing with varying loads or analyzing a circuit's behaviour at multiple points. In addition, it simplifies calculations, conserving time and effort.

Circuit Diagrams & Symbols

Circuit diagrams, also known as schematic diagrams, are graphical representations of electrical circuits that utilize standardized symbols to depict components such as resistors, capacitors, inductors, diodes, and transistors. These symbols facilitate the interpretation of a circuit's structure and function by engineers or hobbyists without requiring physical examination of the actual components.

Here are some common symbols used in circuit diagrams:

Resistor: A simple zigzag line represents a resistor, which opposes the flow of electric current and dissipates energy in the form of heat.

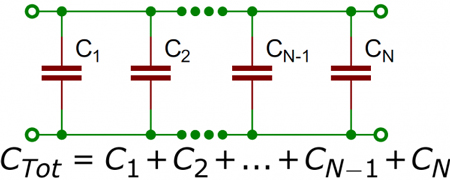

Capacitor: Two parallel lines with a small gap represent a capacitor. The positive plate is marked with a "+" sign in polarized capacitors, and a curved line represents the negative plate.

Inductor: A series of curved or looped lines, similar to a coil, represents an inductor, which stores energy in a magnetic field and opposes changes in current.

Diode: A triangle pointing to a line represents a diode, which allows current to flow in one direction but blocks it in the opposite direction.

Light-emitting diode (LED): Similar to a diode symbol, but with two arrows pointing away from the triangle, representing light emission.

Transistor: Two types of transistors are commonly used: bipolar junction transistors (BJTs) and field-effect transistors (FETs). A BJT symbol comprises a circle or rectangle with three connected leads (emitter, base, and collector). FET symbols are represented by a combination of lines and a vertical arrow with three terminals (gate, source, and drain).

Integrated circuit (IC): A rectangular or square box with multiple leads connected represents an integrated circuit, a complex assembly of numerous electronic components within a single package.

Battery: Alternating long and short parallel lines represent a battery, a source of electrical energy.

Power supply: A circle with an arrow pointing upwards or a combination of letters, such as "Vcc" or "+V," represents a power supply, which provides a constant voltage or current.

Switch: A break in line with an angled line nearby or a pair of lines connected by a diagonal line represents a switch, which controls the flow of current by making or breaking a circuit.

Ground: A series of horizontal lines that decrease in length, a downward-pointing arrow, or the letters "GND" represent a ground connection, which serves as a reference point and provides a return path for electrical currents.

These are just a few examples of the many symbols used in circuit diagrams. Therefore, it's essential to familiarize yourself with these symbols to read or create schematic diagrams for electrical or electronic circuits. The ability of a circuit to store electrical charge is described by Capacitance, a key principle in both electronics and power systems.

Practical Applications & Examples

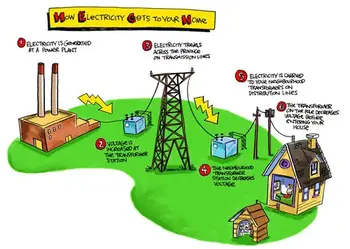

Electrical circuits form the foundation of modern technology, enabling us to harness electricity to operate a wide range of devices and systems. From smartphones and computers to household appliances and industrial machines, circuits power nearly every aspect of daily life.

For example, a simple battery connected to a light bulb demonstrates how a closed loop allows current to flow, converting electrical energy into light and heat. Safe return paths for current are established through the proper installation of Grounding Electrode Conductors, which helps prevent shock and equipment damage.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the simplest electrical circuit?

The simplest circuit consists of a power source (such as a battery), a conductor (like a wire), and a load (like a bulb). Closing the loop lets current flow and power the load.

How do series and parallel circuits differ in real life?

Series circuits share a single path, so if one component fails, the entire circuit stops. Parallel circuits have multiple paths, allowing devices to operate independently.

Why is grounding important in electrical circuits?

Grounding provides a safe return path for electricity. It reduces shock hazards and prevents equipment damage during faults or surges.

What role does resistance play in a circuit?

Resistance controls the amount of current flowing. High resistance limits current, while low resistance allows more current to pass.

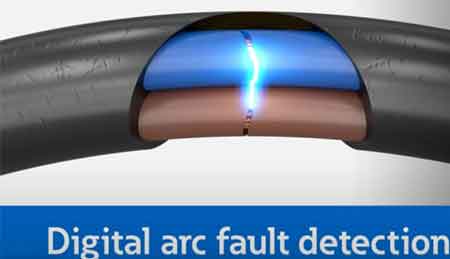

What is the function of a circuit breaker or fuse?

These protective devices interrupt the current when it becomes too high, preventing overheating, fires, and damage to equipment. To safeguard devices and wiring from excessive currents, engineers rely on Overcurrent Protection Device such as fuses and circuit breakers.

What is an electrical circuit? Why It Matters

Electrical circuits are the backbone of modern technology, powering everything from smartphones and appliances to industrial systems. A firm grasp of fundamental circuit principles is crucial for engineers, electricians, and hobbyists, as it unlocks a deeper understanding of the devices that shape everyday life.

Related Articles