What is Electrical Resistance?

Electrical resistance is the measure of how much a material opposes the flow of electric current. Measured in ohms (Ω), it affects voltage, limits current, and plays a vital role in circuit function, energy loss, and power distribution.

What is Electrical Resistance?

Electrical resistance is a key concept in electronics that limits the flow of electricity through a conductor.

✅ Measured in ohms (Ω) to indicate opposition to current flow

✅ Affects voltage, current, and overall power efficiency

✅ Essential in designing safe and effective electrical circuits

Electrical Resistance is an electrical quantity that measures how a device or material reduces the flow of electric current through it. The resistance is measured in units of ohms (Ω). If we make an analogy to water flow in pipes, the resistance is greater when the pipe is thinner, so the water flow is decreased.

Electrical Resistance is a measure of the opposition that a circuit offers to the flow of electric current. You might compare it to the diameter of a hose. In fact, for metal wire, this is an excellent analogy: small-diameter wire has high resistance (a lot of opposition to current flow), while large-diameter wire has low resistance (relatively little opposition to electric currents). Of course, the type of metal makes a difference, too. Iron wire has higher resistance for a given diameter than copper wire. Nichrome wire has still more resistance.

Electrical resistance is the property of a material that opposes the flow of electric current. The resistance of a conductor depends on factors such as the conducting material and its cross-sectional area. A larger cross-sectional area allows more current to flow, reducing resistance, while a smaller area increases it. The unit of electrical resistance is the ohm (Ω), which measures the degree to which a material impedes the flow of electric charge. Conductors with low resistance are essential for efficient electrical systems.

What causes electrical resistance?

An electric current flows when electrons move through a conductor, such as a metal wire. The moving electrons can collide with the ions in the metal. This makes it more difficult for the current to flow, and causes resistance.

Why is electrical resistance important?

Therefore, it is sometimes useful to add components called resistors into an electrical circuit to restrict the flow of electricity and protect the components in the circuit. Resistance is also beneficial because it allows us to shield ourselves from the harmful effects of electricity.

The standard unit of resistance is the ohm. This is sometimes abbreviated by the upper-case Greek letter omega, resembling an upside-down capital U (Ω). In this article, we'll write it out as "ohm" or "ohms."

You'll sometimes hear about kilohms, where 1 kilohm = 1,000 ohms, or about megohms, where 1 megohm = 1,000 kilohms = 1,000,000 ohms.

Electric wire is sometimes rated for resistivity. The standard unit for this purpose is the ohm per foot (ohm/ft) or the ohm per meter (ohm/m). You may also encounter the unit of ohms per kilometre (ohm/km).

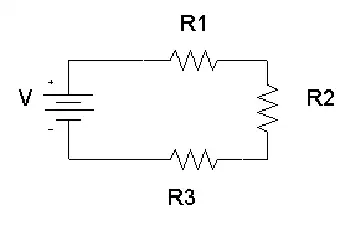

When an IV is placed across 1 ohm of resistance, assuming the power supply can deliver an unlimited number of charge carriers, there will be a current of 1 A. If the resistance is doubled, the current is halved. If the resistance is cut in half, the current doubles. Therefore, the current flow, for a constant voltage, is inversely proportional to the resistance.

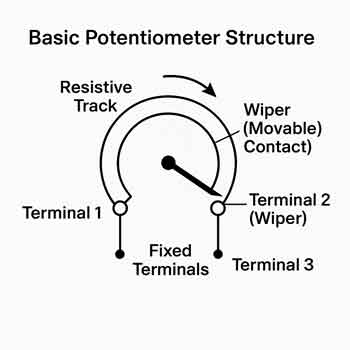

Typically, four-terminal resistors are used to measure current by measuring the voltage drop between the voltage terminals with current flowing through the current terminals. These standards, designed for use with potentiometers for precision current measurement, correspond in structure to the shunts used with millivoltmeters for current measurement with indicating instruments. Current standards must be designed to dissipate the heat they develop at rated current, with only a small temperature rise. They may be oil- or air-cooled; the latter design has a much greater surface area, as heat transfer to still air is less efficient than to oil. An air-cooled current standard with a 20 μω resistance and 2000 A capacity has an accuracy of 0.04%. Very low-resistance oil-cooled standards are mounted in individual oil-filled containers, provided with copper coils through which cooling water is circulated and with propellers to provide continuous oil motion.