Alternative Electricity Key To Carbon Reduction

Alternative electricity integrates renewable energy, smart grids, and distributed generation, combining solar photovoltaics, wind power, hydropower, and battery storage with power electronics and demand response to decarbonize grids and improve reliability.

Understanding How Alternative Electricity Works

Alternative electricity power is essential if we are to find affordable and workable sources of energy before the world completely consumes its limited supply of energy sources. Many countries have started to introduce renewable energy schemes and many countries have invested money into researching and even producing different sources of electricity energy. While it is essential that we become less reliant or not reliant at all on fossil fuels, many forms of alternate energy have their disadvantages as well as their obvious advantages. The advantages of alternate energy far outweigh the disadvantages. For a primer on how modern grids convert primary energy into usable power, see this overview of how electricity is generated across different technologies today.

Wind Energy

Harnessing the power of the wind and using it to our ends is hardly a new idea. Windmills have been and still are used for many different purposes and have been for a great many years, but the improvement of turbines combined with the improved technology to turn the motion of turbine blades into an energy source has seen a marked increase in the use of electricity generating turbines. Detailed diagrams explain how turbine blades capture kinetic energy to generate electricity efficiently under varying wind speeds.

Wind power is very popular, but in order to provide a reasonable amount of power it may prove necessary to have large amounts of turbines. On windy days, and even not so windy days some turbines make a noise that many residents consider to be unbearable. Areas of open countryside are protected by conservation orders, which means they can’t be built there either and if there is no conservation order there are still protestors willing to do almost anything to stop the turbines being built. The only viable option left is to use offshore wind farms and these are being investigated, developed and planned all around the world but it takes too many turbines to create a reasonable amount of power and eventually they will have to be built inland; a matter that will be contested wherever the wind farms are proposed to be built.

Understanding capacity factors and grid integration is key to planning electricity production that balances reliability and community impacts.

Wind power is produced by converting wind energy into electricity. Electricity generation from wind has increased significantly in the United States since 1970. Wind power provided almost 5% of U.S. electricity generation in 2015. These trends mirror broader shifts in electricity generation portfolios as states pursue renewable portfolio standards.

Solar Energy

Solar energy is probably the most common form of alternate energy for everyday people and you can see solar lights ad other solar accessories in many gardens. Governments are beginning to offer grants to assist in paying for photovoltaic roof tiles; these tiles are easily fitted onto your roof and collect the heat from the sun. This heat can either be used to heat water or can even be converted into energy electric power. The advantage for the consumer is that by including a grid tie system you can actually sell unused energy back to the grid. Photovoltaic tiles take the place of ordinary roof tiles and can be perfectly blended to fit the look of the outside of your house. With solar energy you too can help the environment.

Many utilities now offer tariffs that credit exports from rooftop systems, linking household budgets to green electricity choices in a transparent way.

Solar power is derived from energy from the sun. Photovoltaic (PV) and solar-thermal electric are the two main types of technologies used to convert solar energy to electricity. PV conversion produces electricity directly from sunlight in a photovoltaic (solar) cell. Solar-thermal electric generators concentrate solar energy to heat a fluid and produce steam to drive turbines. In 2015, nearly 1% of U.S. electricity generation came from solar power. PV and solar-thermal now sit alongside other major sources of electricity in utility planning models.

Biomass

Ask most people which renewable energy source is the most widely used and they would say either wind or solar, but they’d be wrong or at least they certainly would in America. Since 2000 Biomass has been the most highly produced alternate energy in the United States. Using plant and animal material to create energy isn’t without its downfalls. It would almost certainly meet with competition from residents if biomass power stations were to be created in built up areas. The decomposing plants and animal waste creates an awful smell that is incredibly difficult to mask but it is very renewable (there’s always plants and animal waste).

Biomass is material derived from plants or animals and includes lumber and paper mill wastes, food scraps, grass, leaves, paper, and wood in municipal solid waste (garbage). Biomass is also derived from forestry and agricultural residues such as wood chips, corn cobs, and wheat straw. These materials can be burned directly in steam-electric power plants, or they can be converted to a gas that can be burned in steam generators, gas turbines, or internal combustion engine-generators. Biomass accounted for about 2% of the electricity generated in the United States in 2015.

Other renewable energy sources

These are the main three renewable energy sources that the countries of the world are creating at the moment but there are others. Whether nuclear power is a viable alternate or not is a debate that will undoubtedly rage on forever, but it is a renewable energy and some countries already have extensive capabilities to produce it. Modern technology means that nuclear power stations are safer than they’ve ever been and damage to people, animals or plantation is highly unlikely. However, it takes a long time to develop nuclear power station and even plants that are already being built may take ten years to come to fruition.

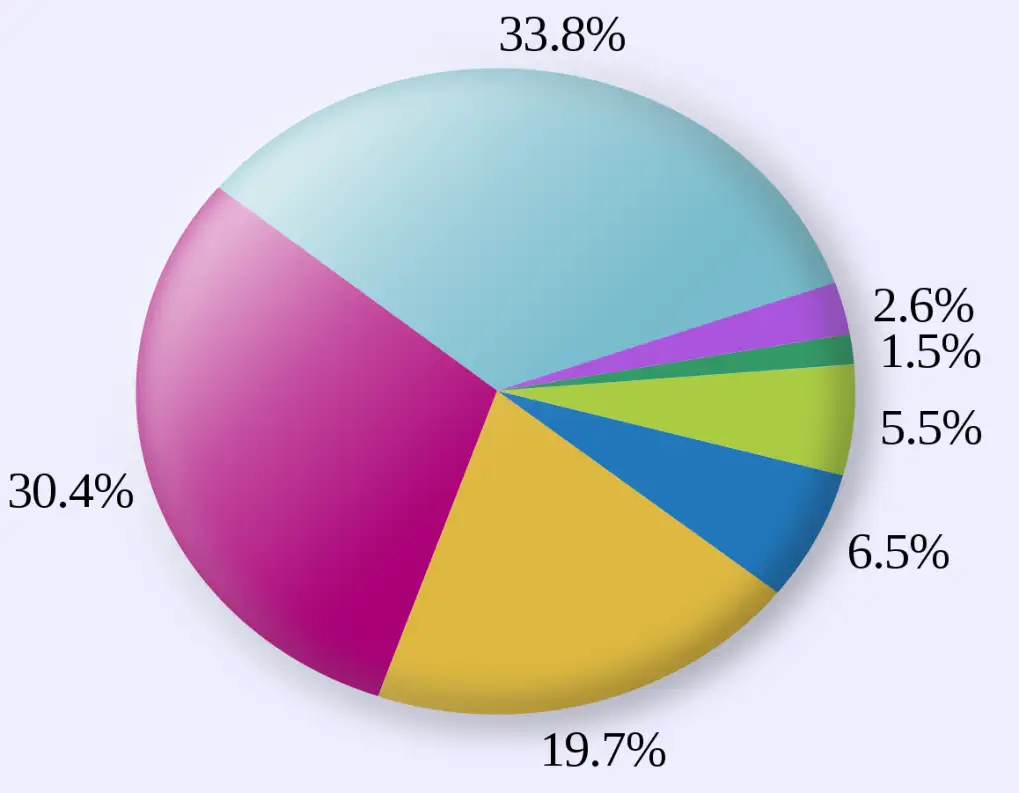

Renewable energy sources provide 13% of U.S. electricity

Hydropower, the source of about 6% of U.S. electricity generation in 2015, is a process in which flowing water is used to spin a turbine connected to a generator. Most hydropower is produced at large facilities built by the federal government, like the Grand Coulee Dam. The West has many of the largest hydroelectric dams, but there are many hydropower facilities operating all around the country. For a deeper look at how turbines and dams convert flow into water electricity, engineers often study case histories from multiple river systems.

Hydro power is used in some countries and uses the motion of waves to create energy. While it is a possibility, the amount of energy produced is minimal and the outlay to set these schemes up is quite large. Without further investigation and improvement in the techniques used it is unlikely that Hydropower will become a major player in the renewable energy world.

Geothermal power comes from heat energy buried beneath the surface of the earth. In some areas of the United States, enough heat rises close enough to the surface of the earth to heat underground water into steam, which can be tapped for use at steam-turbine plants. Geothermal power generated less than 1% of the electricity in the United States in 2015.

_1497174879.webp)