Three Phase Electricity Explained

_1497176406.webp)

Three phase electricity delivers power using three alternating currents that are offset in phase. It provides consistent and efficient energy for industrial, commercial, and high-load applications, improving stability and reducing conductor size.

What is Three Phase Electricity?

Three phase electricity is a power system that uses three alternating currents, each offset by 120 degrees, to deliver constant power flow.

✅ Delivers more efficient and stable power than single-phase systems

✅ Ideal for large motors, commercial buildings, and industrial equipment

✅ Reduces conductor material and energy loss over long distances

Three phase voltage, frequency and number of wires

Three phase electricity is the dominant method of electrical power generation, transmission, and distribution across the industrialized world. Unlike single-phase systems, which rely on a single alternating current, three-phase systems use three separate currents, each 120 degrees out of phase with the others. This setup provides a consistent and balanced power flow, making it significantly more efficient for high-demand applications, such as motors, transformers, and large-scale infrastructure. Understanding the difference between alternating current and direct current is essential to grasp how three-phase systems deliver constant power using offset waveforms.

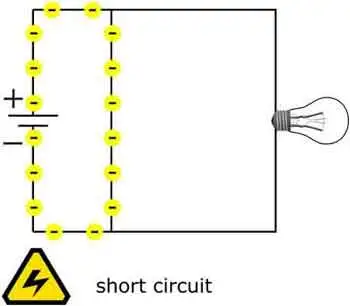

Understanding the Concept

At the heart of a three-phase system are three sinusoidal waveforms, evenly spaced to maintain a continuous flow of energy. When one phase reaches its peak, the others are in different parts of their cycle, ensuring that at any given moment, some power is being delivered. This creates what is known as constant power transfer, a major advantage over single-phase systems that experience power dips between cycles. Since three-phase systems rely heavily on accurate current flow measurement, it’s important to know what ammeters measure and how they help monitor system balance.

For industrial and commercial operations, this stability translates to increased energy efficiency, extended equipment lifespan, and reduced operating costs. Large electric motors, for example, run more smoothly on three-phase power, which avoids the surging and vibration commonly associated with single-phase inputs.

A Brief History

Three phase electricity wasn’t invented by a single person but emerged through the contributions of several pioneers in the late 19th century. Galileo Ferraris in Italy, Nikola Tesla in the United States, and Mikhail Dolivo-Dobrovolsky in Europe all played crucial roles in developing and refining the idea of three-phase alternating current. Tesla’s patents and Dolivo-Dobrovolsky’s practical systems laid the groundwork for what is now a global standard. Engineers use wattmeters to accurately measure real power in three-phase systems, while Watts Law helps calculate the relationships between voltage, current, and power.

Wye and Delta Configurations

Three-phase systems are typically wired in one of two configurations: the Wye (Y) or Delta (Δ) configuration. Each has specific advantages depending on the application:

-

In a Wye connection, each phase is tied to a central neutral point, allowing for multiple voltage levels within the same system. This is common in both commercial and residential applications, where both high and low voltages are required.

-

A Delta connection utilizes a closed loop with no neutral, a configuration commonly found in industrial setups. It delivers the same voltage between all phases and is ideal for running large motors without needing a neutral return path.

One of the most important relationships in these configurations is the √3 ratio between line voltage and phase voltage, a fundamental aspect that engineers use in calculating load, cable sizing, and protective device coordination.

Technical Benefits

Three-phase systems have built-in advantages that go beyond stability. Because the sum of the three phase currents is zero in a balanced load, a neutral wire is often unnecessary. This reduces the amount of conductor material needed, lowering costs and simplifying design. Additionally, three-phase motors naturally create a rotating magnetic field, eliminating the need for external circuitry to start or maintain rotation.

Another major benefit is that power output remains consistent. In single-phase systems, power drops to zero twice per cycle, but three-phase systems deliver non-pulsating power, which is especially important in sensitive or precision equipment. The function of a busbar is especially important in three-phase distribution panels, helping to manage multiple circuit connections efficiently.

Where and Why It’s Used

While most homes use single-phase electricity, three-phase is the standard in virtually all commercial and industrial environments. Factories, data centers, hospitals, and office buildings rely on it to power everything from HVAC systems and elevators to conveyor belts and industrial machines.

Three-phase is also common in electric vehicle (EV) charging stations and renewable energy systems, where efficient, high-capacity delivery is essential. If you're working with three-phase motors or transformers, knowing the role of a conductor and how electrical resistance affects current flow is fundamental to efficient design.

For sites that only have access to single-phase power, phase converters—whether rotary or digital—can simulate three-phase conditions, enabling them to operate three-phase equipment. This flexibility has made three-phase solutions accessible even in remote or rural areas. Three-phase systems often operate at medium voltage, especially in commercial settings, and their stability can reduce the risks of ground faults.

Voltage Levels and Color Codes

Depending on the region, the standard line and phase voltages vary. In North America, typical voltage values include 120/208 volts and 277/480 volts, whereas in Europe and much of Asia, 230/400 volts is more common. Wiring color codes also differ: red/yellow/blue in Europe, black/red/blue in North America, and other variations depending on the country's electrical code. These standards ensure safety, compatibility, and ease of troubleshooting.

The Global Standard for Power

Three-phase electricity is not just a technical solution; it is the foundation of modern electrical infrastructure. Its ability to deliver large amounts of power efficiently, safely, and reliably has made it the system of choice for more than a century. From powering the machines that build our world to the systems that keep us connected, three-phase electricity remains indispensable.

Related Articles

_1497173102.webp)

_1497176752.webp)