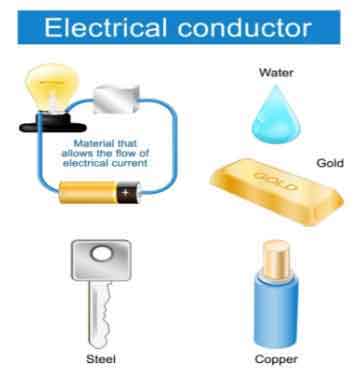

Conductor of electricity describes materials with high electrical conductivity, enabling current flow via free electrons or ions under voltage, such as copper, silver, and aluminum, used in wires, busbars, grounding, and power distribution systems.

What Is a Conductor of Electricity?

A conductor of electricity is a material that easily transmits electric current via free electrons or ions.

✅ Exhibits high conductivity and low resistivity under voltage

✅ Examples: copper, silver, aluminum, graphite, saline water

✅ Enables efficient current flow in cables, busbars, and circuits

A conductor of electricity is a material that allows electric charges to flow through it with little or no resistance. Copper, aluminum, silver, gold, and nickel are some of the most common conductive materials used in electrical engineering. Conductivity is affected by several factors, such as the material's composition, temperature, and impurities. Conductors are distinguished from insulators, which are materials that do not allow electric charge to flow through them. Electrical resistance measures a material's opposition to the flow of electric current. Understanding the properties of conductive materials is essential in designing and operating electrical circuits that power our world. For foundational context, see this overview of electricity to clarify related terms.

The basic principle of a conductor is that it contains free electrons that are not bound to any particular atom. Conductors allow negatively charged electrons to flow easily in an electric field from one atom to another. When a conductor is connected to a source of electric charges, such as a battery, the electrons in the conductor begin to flow in the direction of the electric field. For newcomers, this introduction to conductors expands on how free electrons move under an applied field.

One of the most widely used conductor of electricity is copper. Copper is an excellent conductor of electrical current due to its high conductivity and low electrical resistance. As a result, copper wires are commonly used to transmit electric power over long distances. Copper is also highly durable, making it ideal for use in applications that require long-term reliability.

Aluminum is another common conductor of electrical current. It is cheaper and lighter than copper, which makes it an attractive option for electrical transmission lines. However, aluminum has a lower conductivity than copper, meaning more aluminum is needed to carry the same electric current as copper. This can lead to increased costs for larger electrical applications.

Silver is the best conductor of electrical current known to man. It has the highest electrical conductivity of any metal and is more conductive than copper. However, silver is much more expensive than copper and is only used in applications where its superior conductivity is required.

Gold is also an excellent conductor of electrical current, but it is even more expensive than silver. As a result, gold is mainly used in high-tech applications, such as electronics and aerospace, where its high conductivity and resistance to corrosion are critical.

Nickel is another metal that is a good conductor of electrical current. As a result, it is commonly used in electrical heating applications, such as in electric ovens and toasters.

A material's conductivity measures how easily it allows electric charge to flow through it. Conductivity is affected by several factors, such as the material's composition, temperature, and impurities. Pure water is an example of a poor conductor of electrical current since it contains very few free electrons.

Conductors are distinguished from insulators, which are materials that do not allow electric charge to flow through them. Rubber and plastic are good insulators that cover wires and cables to prevent electrical shock.

Electrical resistance measures a material's opposition to the flow of electric current. The resistance of a conductor depends on the material's composition, temperature, and length. In addition, Ohm's law states that the current through a conductor between two points is directly proportional to the voltage across the two points. For a deeper dive, this guide to electrical resistance explains the underlying physics and units. You can also review the resistance formula to see how voltage, current, and resistance interrelate in practice.

What are the 3 types of conductors?

Metallic conductors: Metallic conductors are materials made of metal that can conduct power. They contain free electrons not bound to any particular atom and can easily move through the metal lattice. Copper, aluminum, silver, gold, and nickel are some examples of metallic conductors.

Electrolytic conductors: Electrolytic conductors are solutions that can conduct due to the presence of dissolved ions. These solutions are typically made of an electrolyte and a solvent. Examples of electrolytic conductors include solutions of salt, acid, and base.

Semiconductor conductors: Semiconductor conductors are materials that have electrical conductivity between the conductors and insulators. They are used in electronic devices such as transistors, diodes, and solar cells. Some common semiconductor materials include silicon, germanium, and gallium arsenide.

What is the main conductor?

Copper is the most commonly used conductor due to its high electrical conductivity and low electrical resistance. It is also highly durable, making it ideal for use in applications that require long-term reliability. For example, copper wires are commonly used in power distribution systems to transmit electric power over long distances.

What properties does a conductor have?

In addition to high electrical conductivity and low electrical resistance, conductors also have high thermal conductivity, meaning they can transfer heat efficiently. In addition, they have low melting points, allowing them to be easily molded and shaped. Conductors are also ductile, easily drawn into thin wires without breaking.

What makes a good conductor of electricity?

A good conductor of electricity has a high number of free electrons available for conducting an electric charge. It also has low electrical resistance, meaning that it does not impede the flow of electric charge. In general, metals make good conductors of power because they have a high number of free electrons.

How does a conductor conduct electricity?

When a conductor is connected to a source of electric charge, such as a battery, the electric field causes free electrons in the conductor to move in the direction of the field. This movement of free electrons creates an electric current, the flow of electric charge.

What are some examples of good conductors?

Some examples of good conductors include copper, aluminum, silver, gold, and nickel. These metals have many free electrons and low electrical resistance, making them ideal for conducting an electric charge.

What is the difference between a conductor and an insulator?

The main difference between a conductor and an insulator is that a conductor allows an electric charge to flow with little or no resistance. In contrast, an insulator does not allow electric charge to flow. Insulators are typically used to cover or insulate conductors to prevent electric shock or keep the electric charge within a circuit. For a formal definition that complements this comparison, consult a concise conductor definition for precise terminology.

What is the role of a conductor in an electrical circuit?

The role of a conductor in an electrical circuit is to provide a path for the flow of electric charge. In addition, conductors connect the different components of an electrical circuit, such as resistors, capacitors, and inductors. They also transmit electric power from one place to another through power lines. For component selection context, see common types of resistors that conductors connect within practical circuits.

What is the importance of conductivity in electrical systems?

Conductivity is an essential property of materials used in electrical systems because it determines how easily an electric charge can flow through a material. Materials with high conductivity are used in applications where efficient transmission of electric power is required, such as in power distribution systems. Conversely, materials with low conductivity are used as insulators to prevent the flow of electric charge.

How does the thickness of a conductor affect its ability to conduct?

The thickness of a conductor affects its ability to conduct electrical current because thicker conductors have a lower electrical resistance. This means thicker conductors can carry more electric current with less power loss due to resistance. For example, a thin copper wire may not be able to have as much current as a thicker copper wire of the same length due to the increased resistance of the thinner wire. Therefore, the thickness of a conductor is an essential consideration in designing electrical circuits, especially for high-current applications where minimizing power loss due to resistance is critical. Additionally, thicker conductors are more durable and less likely to break under stress, making them more suitable for applications where mechanical stress is present, such as bridges and buildings.

If these tradeoffs are new to you, this primer on electrical resistance connects cross-sectional area to current flow with clear examples.

Related Articles