Electricity Supplier - Make The Right Choice

_1497153600.webp)

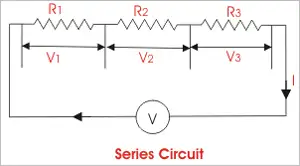

Electricity supplier delivers power via transmission and distribution networks, managing tariffs, load forecasting, SCADA, and power quality, integrating renewables, smart meters, and demand response to ensure grid reliability, compliance, and efficient kWh billing.

What Is an Electricity Supplier?

An electricity supplier procures and delivers power, manages tariffs, and ensures grid reliability and power quality.

✅ Energy procurement and wholesale market participation

✅ Distribution coordination, SCADA monitoring, and outage management

✅ Tariff design, metering, billing, and power quality compliance

Who is my electricity supplier?

In Canada and the United States, it’s easy to learn which energy provider serves your property or residence. It depends on whether you are trying to find your electricity and natural gas supplier. Sometimes, homes and businesses have the power to choose their energy service utility company and the products and service they provide. Customers are free to choose. It's a competitive energy marketplace. For a plain-language primer on infrastructure, see the electricity supply overview to understand typical delivery steps.

If you use both services, your property might have the same local distribution company for both fuels, – commonly known as a "duel fuel supplier". But if your utility records are stored separately, you might need to more research to learn who supplies your natural gas services and your electricity services separately. If you are curious where the power originates, this guide to how electricity is generated explains common fuel sources and grid integration.

Here is a list of accredited Electricity Suppliers in Canada

https://www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/mc-mc.nsf/eng/lm00525.html

Market dynamics can vary by province, and recent electricity demand trends in Canada help explain seasonal shifts in offers.

Here is a list of accredited Electricity Suppliers in the United States.

https://www.electricchoice.com/blog/25-top-providers-part-1/

When comparing providers, consult current electricity price benchmarks to contextualize quoted rates.

Who can supply electricity?

All electricity supplier companies must have a licence from the Office of Gas and Electricity Markets (Ofgem). One of the licence conditions is that a company must produce codes of practice on:

Although the codes of practice are not legally enforceable, they will be useful when negotiating with a company and any breach should be reported to governmental regulatory authorities. Understanding the basics in this introduction to what electricity is can make those obligations clearer.

Choosing an electricity supplier

You can change your company if you wish. If you are considering changing your company you should be aware that the pricing structures, services offered and policies will differ between the different companies.You should carefully check the information and contracts of the competing electricity suppliers, and compare these to your current terms, to make sure that you choose the best deal for your needs. A lot depends on your gas bills or electricity bill, and your location by postal code. You can also estimate bill impacts by applying tips from this guide on how to save electricity while comparing plans.

Dual fuel offers

Dual fuel is the supply of gas and electricity by the same company. Some gas and electricity suppliers are licensed separately by Ofgem to supply customers with both fuels. Some companies will supply both fuels under one contract, while others will give one contract for gas and another for electricity. For households with high usage, reviewing your typical electricity power consumption patterns can reveal whether dual fuel makes financial sense.

Electricity Suppliers who make dual offers will often give a discount off the total bill as they can make administrative savings by issuing combined bills and collecting combined payments. However, this does not necessarily mean that the cost of gas and electricity

- procedures for complaints

- payment of bills, arrangements for dealing with arrears and prepayment meters

- site access procedures

- energy efficiency advice

- services for older, disabled and chronically sick people. As part of this code of practice, the company must keep a register of these people and provide services to help those who are blind and partially sighted or deaf or hearing impaired. Especially during a power outage, it is important that these customers are restored asap.The customer may have to pay for some of these services.

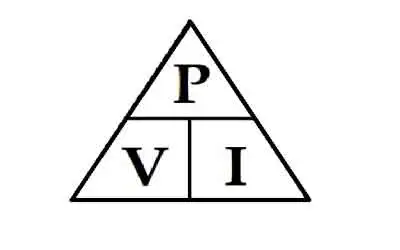

- how you will be charged for your electricity supply. Some companies may make a fixed standing charge and then a unit charge for the amount of electricity used; an company may not make a standing charge, but charge a higher unit price

- whether different charges apply to different periods during the day

- if cheaper prices are offered for particular payment methods, for example, if you pay by direct debit

- what service standards each company is offering, for example, for repairs, extra help for older or disabled customers.All electricity suppliers must keep a list of their customers who ask to be identified as pensioners, chronically sick or disabled.The electricity supplier must tell all its customers that it keeps such a list and give information on how customers can be added to the list

- the company's policies, for example, on debt and disconnection.