Prospective Fault Current Meaning Explained

Prospective fault current (PFC) is the highest electric current that can flow in a system during a short circuit. It helps determine equipment ratings, breaker capacity, and safety measures in electrical installations to prevent overheating, fire, or component failure.

What is the Meaning of Prospective Fault Current?

Prospective fault current refers to the maximum current expected during a short circuit at any point in an electrical system.

✅ Helps size circuit breakers and fuses for safe disconnection

✅ Ensures compliance with installation and safety codes

✅ Prevents equipment damage from excessive short-circuit current

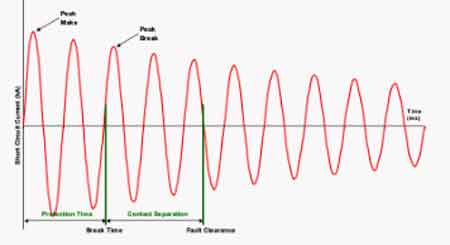

Prospective fault current (PFC) is a key factor in the safety and design of electrical systems. It represents the maximum current that could flow in the event of a fault, such as a short circuit. Understanding PFC is essential for selecting protective devices that can handle fault conditions safely. This article explores what PFC is, how it is measured, and its importance for electrical installations, while addressing key questions. Understanding electrical short circuits is key to calculating prospective fault current and ensuring system safety.

When measuring prospective short circuit current in an electrical system, it’s essential to perform tests between L1 N CPC and L2 N CPC to assess the fault current across different phases and protective conductors. These measurements help identify the maximum prospective fault current present in the system, especially at points involving live conductors. Whether taking note of a single-phase supply or between line conductors on a three-phase supply, proper testing protocols must be followed. Technicians should always use insulated test leads rated for the expected voltage and current levels, and please refer to the test meter manufacturer’s instruction for safe and accurate operation. Reliable results ensure that the protective devices can safely interrupt fault conditions, preventing system damage and ensuring compliance with fault current protection standards.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is it Important?

Prospective fault current refers to the maximum current that could pass through a system during a fault. The PFC helps determine the breaking capacity of fuses and circuit breakers, ensuring these protective devices can handle high currents safely. This is vital for protecting the electrical installation and those working near it.

Understanding PFC is critical for ensuring increased safety for employees and third parties. Protective devices must be selected to handle PFC; otherwise, they may fail to operate correctly, leading to severe consequences, such as fires or injuries. To fully grasp how PFC affects energy flow, it’s useful to review the concept of electrical resistance in a circuit.

How is Prospective Fault Current Measured or Calculated?

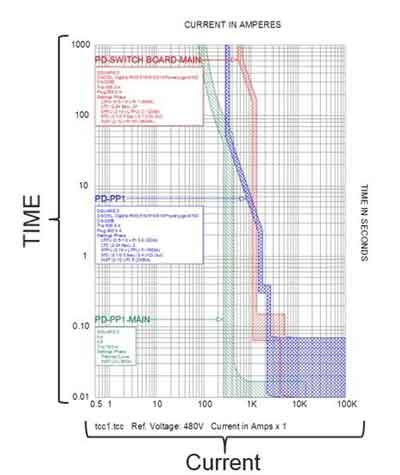

PFC can be measured or calculated using tools such as a multifunction tester, often during fault current testing. The instrument uses a single-phase supply or between line conductors on a three-phase supply to measure the maximum potential current at various points in the installation. Testing often involves checking currents between L1 N CPC, L2 N CPC, and L3 N CPC, which measure current between the lines to neutral in a three-phase system.

When performing these tests, technicians should follow regulation 612.11 of a single-phase supply or between line conductors on a three-phase supply, ensuring that simple and circuit protective conductors are all connected correctly. Accurate testing must also account for maximum current flow. Live testing requires extreme caution, and it is important to refer to the test meter manufacturer’s instructions to ensure proper usage and safety. In three-phase systems, 3-phase electricity significantly impacts how fault current behaves during a short circuit.

What is the difference between PFC and Short-Circuit Current?

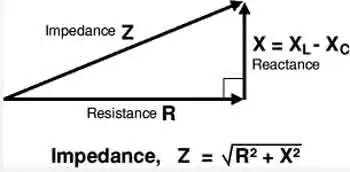

Though often confused, prospective fault current and short-circuit current are distinct. Prospective fault current is the theoretical maximum current that could flow in a fault, used to predict the worst-case scenario for selecting protective devices. Short-circuit current refers to the actual current that flows during a fault, which depends on real-time conditions such as circuit impedance. Prospective fault current is one of the many concepts that form the foundation of electricity fundamentals.

How Does Prospective Fault Current Impact the Selection of Protective Devices?

The calculation of PFC plays a critical role in selecting the correct protective devices. Circuit breakers and fuses must have a breaking capacity that matches or exceeds the prospective fault current in the system. If the PFC exceeds the breaking capacity, the protective device may fail, leading to dangerous electrical hazards.

For instance, fault current testing using a multifunction tester between phases and neutral (L1, L2, L3) ensures that protective devices are rated to handle the highest potential fault current in the system. Proper circuit protection ensures that the system can interrupt faults safely, minimizing the risks to workers and equipment.

What Standards and Regulations Govern Prospective Fault Current Calculations?

Various standards, such as IEC 60909, govern how PFC is calculated and how protective devices are selected. These regulations ensure that electrical systems are designed to handle maximum fault conditions safely. Regulation 612.11 further specifies how live testing should be conducted using proper equipment and safety protocols.

It is essential to test PFC at relevant points in the system and follow testing standards to ensure compliance and safety. Devices selected based on PFC calculations help ensure that electrical systems can withstand faults and maintain reliable operation.

Prospective fault current is a crucial element in the safety and reliability of electrical installations. By calculating PFC, engineers can select protective devices that ensure safe operation in the event of a fault. Testing for fault currents at different points in the system and adhering to regulations are essential steps in preventing hazardous conditions.

By choosing protective devices with the appropriate breaking capacity and following safe testing practices, electrical installations can handle fault conditions and protect both workers and equipment from harm. Selecting protective devices that match the PFC is essential for reliable electric power systems design.

Related Articles