Electricity and Magnetism - Power Explained

_1497200293.webp)

Electricity and magnetism are interconnected forces forming electromagnetism, which explains electric currents, magnetic fields, and their interactions. These principles power motors, generators, transformers, and more in modern electrical and magnetic systems.

What is: "Electricity and Magnetism"

Electricity and magnetism are fundamental forces in physics that form the basis of electromagnetism.

✅ Describe how electric charges and magnetic fields interact in nature and technology

✅ Underlie the function of motors, transformers, and generators

✅ Explain current flow, induction, and electromagnetic waves

Electricity - What is it?

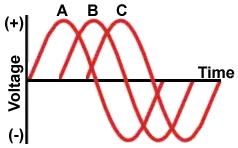

Electricity is a form of energy that is transmitted through copper conductor wire to power the operation of electrical machines and devices, including industrial, commercial, institutional, and residential lighting, electric motors, electrical transformers, communications networks, home appliances, and electronics.

When charged particles flow through the conductor, we call it "current electricity". This is because when the charged particles flow through wires, electricity also flows. We know that current means the flow of anything in a particular direction. For example, the flow of water. Similarly, the flow of electricity in a specific direction is referred to as an electric current. The interplay of charge, field, and force is explored in what is electric load, covering how power is delivered in electromagnetic systems.

When an electric current flows, it produces a magnetic field, a concept closely tied to Faraday's Law of Induction, which underpins much of modern electrical engineering.

Magnetism - What is it?

Magnetism is a type of attractive or repulsive force that acts up to certain distance at the speed of light. The distance up to which this attractive or repulsive force acts is called a "magnetic field". Magnetism is caused by the moving electric charges (especially electrons). When two magnetic materials are placed close to each other, they experience an attractive or repulsive force. To understand magnetic field strength and units, our magnetic induction basics in induction page discusses flux and Teslas.

What is the relationship between electricity and magnetism?

In the early days, scientists believed that there were two uniquely separate forces. However, James Clerk Maxwell proved that these two separate forces were actually interrelated.

In 1820, Hans Christian Ørsted observed a surprising phenomenon: when he switched on the battery from which the electric current was flowing, the compass needle moved away from the north pole. After this experiment, he concluded that the electric current flowing through the wire produces a magnetic field.

Electricity and magnetism are closely related to each other. The electric current flowing through the wire produces a circular magnetic field outside the wire. The direction (clockwise or counterclockwise) of this magnetic field depends on the direction of the electric current.

Similarly, a changing magnetic field generates an electric current in a wire or conductor. The relationship between them is called electromagnetism.

Electricity and magnetism are interesting aspects of electrical sciences. We are familiar with the phenomenon of static cling in our everyday lives - when two objects, such as a piece of Saran wrap and a wool sweater, are rubbed together, they cling.

One feature of this that we don't encounter too often is static "repulsion" - if each piece of Saran wrap is rubbed on the wool sweater, then the pieces of Saran wrap will repel when brought near each other. These phenomena are interpreted in terms of the objects acquiring an electric charge, which has the following features:

-

There are two types of charge, which by convention are labelled positive and negative.

-

Like charges repel, and unlike charges attract.

-

All objects may have a charge equal to an integral number of a basic unit of charge.

-

Charge is never created or destroyed.

To explore how electric and magnetic forces interact at a distance, see what is static electricityis, which includes examples like static cling and repulsion.

Electric Fields

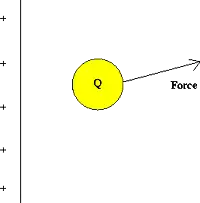

A convenient concept for describing these electric current and magnetic current forces is that of electric field currents. Imagine that we have a fixed distribution of charges, such as on the plate below, and bring a test charge Q into the vicinity of this distribution.

Fig. 1 Test charge in the presence of a fixed charge distribution

This charge will experience a force due to the presence of the other charges. One defines the electric field of the charge distribution as:

The electric field is a property of this fixed charge distribution; the force on a different charge Q' at the same point would be given by the product of the charge Q' and the same electric field. Note that the electric field at Q is always in the same direction as the electric force.

Because the force on a charge depends on the magnitude of the charges involved and the distances separating them, the electric field varies from point to point, both in magnitude and direction.

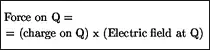

By convention, the direction of the electric field at a point is the direction of the force on a positive test charge placed at that point. An example of the electric field due to a positive point charge is given below.

Fig. 2: Electric field lines of a positive charge

Power and Magnetic Fields

A phenomenon apparently unrelated to power is electromagnetic fields. We are familiar with these forces through the interaction of compasses with the Earth's magnetic field, or the use of fridge magnets or magnets on children's toys. Magnetic forces are explained in terms very similar to those used for electric forces:

- There are two types of magnetic poles, conventionally called North and South

- Like poles repel, and opposite poles attract

However, this attraction differs from electric power in one important aspect:

- Unlike electric charges, magnetic poles always occur in North-South pairs; there are no magnetic monopoles.

Later on we will see at the atomic level why this is so.

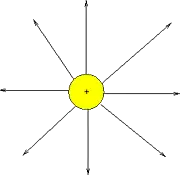

As in the case of electric charges, it is convenient to introduce the concept of a magnetic field in describing the action of magnetic forces. Magnetic field lines for a bar magnet are pictured below.

Fig. 3: Magnetic field lines of a bar magnet

One can interpret these lines as indicating the direction that a compass needle will point if placed at that position.

The strength of magnetic fields is measured in units of Teslas (T). One tesla is actually a relatively strong field - the earth's magnetic field is of the order of 0.0001 T.

Magnetic Forces On Moving Charges

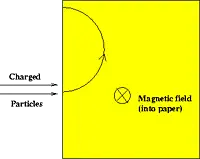

One basic feature is that, in the vicinity of a magnetic field, a moving charge will experience a force. Interestingly, the force on the charged particle is always perpendicular to the direction it is moving. Thus, magnetic forces cause charged particles to change their direction of motion, but they do not change the speed of the particle.

This property is utilized in high-energy particle accelerators to focus beams of particles, which ultimately collide with targets to produce new particles, including gamma rays and radio waves.

Another way to understand these forces of electricity and magnetism is to realize that if the force is perpendicular to the motion, then no work is done. Hence, these forces do no work on charged particles and cannot increase their kinetic energy.

If a charged particle moves through a constant magnetic field, its speed stays the same, but its direction is constantly changing. A device that utilizes this property is the mass spectrometer, which is used to identify elements. A basic mass spectrometer is pictured below.

Figure 4: Mass spectrometer

In this device, a beam of charged particles (ions) enters a region of a magnetic field, where they experience a force and are bent in a circular path. The amount of bending depends on the mass (and charge) of the particle, and by measuring this amount one can infer the type of particle that is present by comparing it to the bending of known elements.

Magnet Power From Electric Power

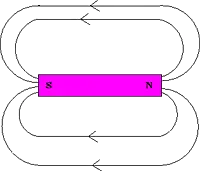

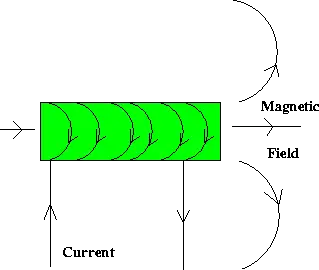

A connection was discovered (accidentally) by Orsted over 100 years ago, when he noticed that a compass needle is deflected when brought into the vicinity of a current-carrying wire. Thus, currents induce magnetic fields in their vicinity. An electromagnet is simply a coil of wires which, when a current is passed through, generates a magnetic field, as below.

Figure 5: Electromagnet

Another example is in an atom, where an electron is a charge that moves around the nucleus. In effect, it forms a current loop, and hence, a magnetic field may be associated with an individual atom. It is this basic property which is believed to be the origin of the magnetic properties of various types of materials found in nature.

Maxwell's equations (also known as Maxwell's theory) are a set of coupled partial differential equations that, together with the Lorentz force law, form the foundation of classical electromagnetism, which deals with electromagnetic radiation, electromagnetic waves, and electromagnetic force. For a deeper understanding of the magnetic effects of electrical current, our article on electromagnetic induction explains how magnetic fields can generate electricity in conductors.

_1497176406.webp)