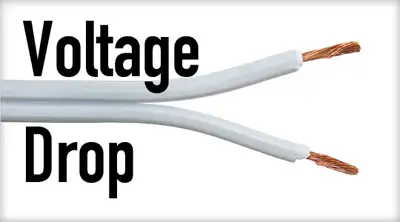

Voltage Drop Explained

Voltage drop occurs when electrical voltage decreases as current flows through a conductor. It can cause poor equipment performance, energy loss, and overheating. Discover how selecting the proper wire size and material can help minimize voltage drop in electrical systems.

Power Quality Analysis Training

Request a Free Power Quality Training Quotation

What is Voltage Drop?

Voltage drop (VD) is a common issue in electrical systems where the voltage (V) at the end of a circuit is lower than at the beginning due to resistance in the wiring.

✅ A decrease in V along a wire or circuit due to resistance or impedance

✅ Leads to reduced equipment performance and higher energy consumption

✅ Prevented by proper wire sizing, shorter runs, and low-resistance materials

Voltage Drop Definition

Voltage drop can lead to inefficient equipment operation or even failure. Solving electrical potential drop involves ensuring proper wire sizing, minimizing long-distance wiring runs, and using materials with lower resistance. Calculating the voltage drop for specific circuits and adjusting the installation accordingly helps maintain optimal performance and prevent power loss.

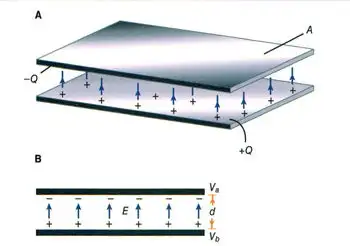

Any length or size of wires will have some resistance, and running a current through this dc resistance will cause the voltage to drop. As the length of the cable increases, so does its resistance and reactance increase in proportion. Hence, circuit V drop is particularly a problem with long cable runs, for example, in larger buildings or on larger properties such as farms. This technique is often used when properly sizing conductors in any single-phase, line-to-line electrical circuit. This can be measured with a voltage drop calculator.

Electrical cables have a carrying capacity of current that always presents inherent resistance, or impedance, to the flow of current. Voltage drop is measured as the amount of loss which occurs through all or part of a circuit due to what is called cable "impedance" in volts.

Too much resistance in wires, otherwise known as " excessive voltage drop ", in a cable's cross-sectional area can cause lights to flicker or burn dimly, heaters to heat poorly, and motors to run hotter than normal and burn out. This condition causes the load to work harder with less energy, pushing the current.

Voltage Drop per 100 Feet of Copper Wire (Single Phase, 60 Hz, 75°C, 120V Circuit)

(Values are approximate, in volts, for a 2% limit)

| Wire Size (AWG) | Max Current (Amps) | Max Distance (Feet) | Voltage Drop (at max distance) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 14 | 15 | 50 | 2.4 V |

| 12 | 20 | 60 | 2.4 V |

| 10 | 30 | 80 | 2.4 V |

| 8 | 40 | 100 | 2.4 V |

| 6 | 55 | 130 | 2.4 V |

| 4 | 70 | 160 | 2.4 V |

| 2 | 95 | 200 | 2.4 V |

| 1/0 | 125 | 250 | 2.4 V |

Key Takeaways

-

Larger wires (lower AWG numbers) carry more current with less VD.

-

Longer distances require thicker wires to stay within VD limits.

-

A 2% VD is often used as a conservative design target in electrical systems.

How is this solved?

To decrease the voltage drop in a circuit, you need to increase the size (cross-section) of your conductors – this is done to lower the overall resistance of the cable length. Certainly, larger copper or aluminum cable sizes increase the cost, so it’s essential to calculate the voltage drop and determine the optimum wire size that will reduce voltage drop to safe levels while remaining cost-effective.

How do you calculate voltage drop?

Voltage drop refers to the loss of electricity that occurs when current flows through a resistance. The greater the resistance, the greater the voltage drop. To check the voltage drop, use a voltmeter connected between the points where the voltage drop is to be measured. In DC circuits and AC resistive circuits, the total of all the voltage drops across series-connected loads should add up to the V applied to the circuit (Figure 1).

Fig. 1. Measuring voltage drops across loads

Read our companion article Voltage Drop Calculator. For more information, see our article: Voltage Drop Formula.

Each load device must receive its rated power to operate properly. If not enough is available, the device will not operate as it should. You should always be certain that the V you are going to measure does not exceed the range of the voltmeter. This may be difficult if the V is unknown. If such is the case, you should always start with the highest range. Attempting to measure a V higher than the voltmeter can handle may cause damage to the voltmeter. At times you may be required to measure a V from a specific point in the circuit to ground or a common reference point (Figure 8-15). To do this, first connect the black common test probe of the voltmeter to the circuit ground or common. Then connect the red test probe to whatever point in the circuit you want to measure.

To accurately calculate the drop for a given cable size, length, and current, you need to accurately know the resistance of the type of cable you’re using. However, AS3000 outlines a simplified method that can be used.

The table below is taken from AS3000 electrical code, which specifies ‘Amps per %Vd‘ (amps per percentage VD) for each cable size. To calculate the dop for a circuit as a percentage, multiply the current (amps) by the cable length (metres); then divide this Ohm number by the value in the table.

For example, a 30m run of 6 mm² cable carrying 3-phase 32A will result in a 1.5% drop: 32A × 30m = 960A / 615 = 1.5%.

Learn more about real-world voltage drop issues on our Voltage Dropping in Power Quality page.

Related Pages