Lenz's Law Explained

Lenz’s Law is a principle of electromagnetic induction stating that induced current flows in a direction that opposes the change in magnetic flux producing it. This rule ensures energy conservation and explains how circuits, coils, generators, and transformers behave in changing fields.

What is Lenz’s Law?

Lenz’s Law, rooted in Faraday’s Law of Induction, states that the direction of an induced current or electromotive force (emf) always opposes the change in magnetic flux that produced it. This principle safeguards conservation of energy in electromagnetic systems.

✅ Explains opposing force in induced current and magnetic fields

✅ Fundamental to understanding circuits, transformers, and generators

✅ Practical in energy conversion, electric motors, and induction device

Lenz's Law, named after the Russian physicist Heinrich Lenz (1804-1865), is a fundamental principle in electromagnetism. It states that the direction of the induced electromotive force (emf) in a closed conducting loop always opposes the change in magnetic flux that caused it. This means that the induced current creates a magnetic field that opposes the initial change in magnetic flux, following the principles of conservation of energy. A strong grounding in basic electricity concepts makes it easier to see why Lenz’s Law is central to modern circuit design.

Understanding Lenz's Law enables us to appreciate the science behind various everyday applications, including electric generators, motors, inductors, and transformers. By exploring the principles of Lenz's Law, we gain insight into the inner workings of the electromagnetic world that surrounds us. Engineers use this principle when designing three-phase electricity systems and 3-phase power networks to maintain energy balance.

Lenz's Law, named after the Russian physicist Heinrich Lenz (1804-1865), is a fundamental principle that governs electromagnetic induction. It states that the induced electromotive force (emf) in a closed conducting loop always opposes the change in magnetic flux that caused it. In simpler terms, the direction of the induced current creates a magnetic field that opposes the initial change in magnetic flux.

Lenz's Law is a fundamental law of electromagnetism that states that the direction of an induced electromotive force (EMF) in a circuit is always such that it opposes the change that produced it. Mathematically, Lenz's Law can be expressed as:

EMF = -dΦ/dt

Where EMF is the electromotive force, Φ is the magnetic flux, and dt is the change in time. The negative sign in the equation indicates that the induced EMF is in the opposite direction to the change in flux.

Lenz's Law is closely related to Faraday's Law of electromagnetic induction, which states that a changing magnetic field induces an EMF in a circuit. Faraday's Law can be expressed mathematically as:

EMF = -dΦ/dt

where EMF is the electromotive force, Φ is the magnetic flux, and dt is the change in time.

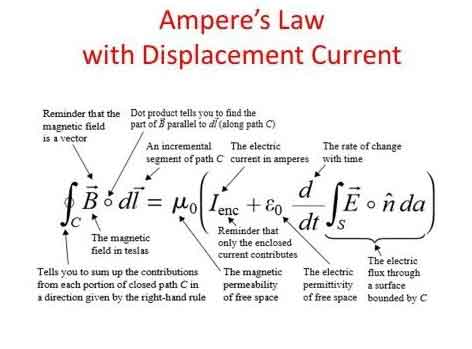

Ampere's Law and the Biot-Savart Law are also related to Lenz's Law, as they describe the behaviour of electric and magnetic fields in the presence of currents and charges. Ampere's Law states that the magnetic field around a current-carrying wire is proportional to the current and the distance from the wire. The Biot-Savart Law describes the magnetic field produced by a current-carrying wire or a group of wires. Because Lenz’s Law governs the behavior of induced currents, it directly complements Ampere’s Law and the Biot-Savart Law in explaining magnetic fields.

Together, these laws provide a complete description of the behaviour of electric and magnetic fields in various situations. As a result, they are essential for understanding the operation of electric motors, generators, transformers, and other devices.

To better understand Lenz's Law, consider the scenario of a bar magnet moving toward a coil of wire. When the magnet moves closer to the coil, the number of magnetic field lines passing through the coil increases. According to Lenz's Law, the polarity of the induced emf in the coil is such that it opposes the increase in magnetic flux. This opposition creates an induced field that opposes the magnet's motion, ultimately slowing it down. Similarly, when the magnet is moved away from the coil, the induced emf opposes the decrease in magnetic flux, creating an induced field that tries to keep the magnet in place.

The induced field that opposes the change in magnetic flux follows the right-hand rule. If we hold our right hand around the coil such that our fingers point in the direction of the magnetic field lines, our thumb will point in the direction of the induced current. The direction of the induced current is such that it creates a magnetic field that opposes the change in the magnetic flux.

The pole of the magnet also plays a crucial role in Lenz's Law. When the magnet's north pole moves towards the coil, the induced current creates a magnetic field that opposes the north pole's approach. Conversely, when the magnet's south pole moves towards the coil, the induced current creates a magnetic field that opposes the south pole's approach. The direction of the induced current follows the right-hand rule, as we discussed earlier.

It is related to Faraday's Law of Electromagnetic Induction, which explains how a changing magnetic field can induce an electromotive force (emf) in a conductor. Faraday's Law mathematically describes the relationship between the induced electromotive force (emf) and the rate of change of magnetic flux. It follows Faraday's Law, as it governs the direction of the induced emf in response to the changing magnetic flux. To fully understand how electromagnetic induction works, it is helpful to see how Faraday’s discoveries laid the foundation for Lenz’s Law.

It is also related to the phenomenon of eddy currents. Eddy currents are loops of electric current induced within conductors by a changing magnetic field. The circulating flow of these currents generates their magnetic field, which opposes the initial magnetic field that created them. This effect is in line with Lenz's Law and has practical applications, such as in the braking systems of trains and induction cooktops.

Lenz's Law has numerous practical applications in our daily lives. For example, it plays a significant role in the design and function of electric generators, which convert mechanical energy into electrical energy. In a generator, a rotating coil experiences a changing magnetic field, resulting in the generation of an electromotive force (emf). The direction of this induced emf is determined by Lenz's Law, which ensures that the system conserves energy. Similarly, electric motors operate based on Lenz's Law. In an electric motor, the interaction between the magnetic fields and the induced electromotive force (emf) creates a torque that drives the motor. In transformers, including 3-phase padmounted transformers, Lenz’s Law explains why flux changes are controlled for efficiency and safety.

Lenz's Law is an essential concept in the design of inductors and transformers. Inductors are electronic components that store energy in their magnetic field when a current flows through them. They oppose any change in the current, following the principles of Lenz's Law. Transformers, which are used to transfer electrical energy between circuits, utilize the phenomenon of electromagnetic induction. By understanding it, engineers can design transformers.

Related Articles

_1497153600.webp)