DHS/FBI Alert: Russian Government Cyber Activity Targeting Power Grid

By R. W. Hurst, Editor

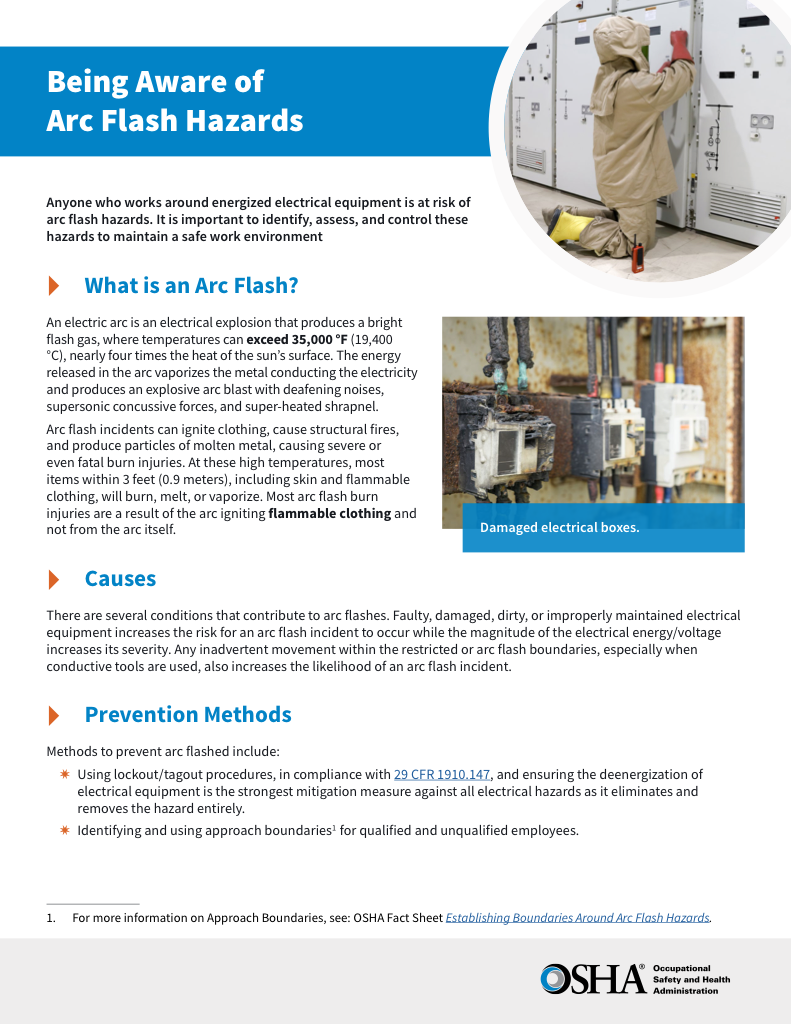

Download Our OSHA 4475 Fact Sheet – Being Aware of Arc Flash Hazards

- Identify root causes of arc flash incidents and contributing conditions

- Apply prevention strategies including LOTO, PPE, and testing protocols

- Understand OSHA requirements for training and equipment maintenance

DHS FBI Alert provides a joint advisory and threat bulletin on cybersecurity, terrorism risks, and critical infrastructure protection, offering mitigation guidance, IOCs, and timely warnings to enhance public safety and incident response.

What Is a DHS FBI Alert?

A coordinated advisory from DHS and the FBI sharing threats, IOCs, and mitigation steps to protect critical systems.

✅ Joint DHS-FBI threat intelligence and advisories

✅ Includes IOCs, TTPs, and mitigation guidance

✅ Focus on critical infrastructure and public safety

In an unprecedented alert, the US Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and FBI have warned of persistent attacks by Russian government hackers on critical US government sectors, including energy, nuclear, commercial facilities, water, aviation and manufacturing.

The alert details numerous attempts extending back to March 2016 when Russian cyber operatives targeted US government and infrastructure.

The DHS and FBI said: “DHS and FBI characterise this activity as a multi-stage intrusion campaign by Russian government cyber-actors who targeted small commercial facilities’ networks, where they staged malware, conducted spear phishing and gained remote access into energy sector networks.

What follows is an excerpt from the DHS/FBI Alert:

Systems Affected

- Domain Controllers

- File Servers

- Email Servers

- Overview

This joint Technical Alert (TA) is the result of analytic efforts between the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). This alert provides information on Russian government actions targeting U.S. Government entities as well as organizations in the energy, nuclear, commercial facilities, water, aviation, and critical manufacturing sectors. It also contains indicators of compromise (IOCs) and technical details on the tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) used by Russian government cyber actors on compromised victim networks. DHS and FBI produced this alert to educate network defenders to enhance their ability to identify and reduce exposure to malicious activity. For a broader view of grid risk management, the resource on grid cybersecurity strategy discusses layered defenses across utilities.

Sign Up for Electricity Forum’s Smart Grid Newsletter

Stay informed with our FREE Smart Grid Newsletter — get the latest news, breakthrough technologies, and expert insights, delivered straight to your inbox.

DHS and FBI characterize this activity as a multi-stage intrusion campaign by Russian government cyber actors who targeted small commercial facilities’ networks where they staged malware, conducted spear phishing, and gained remote access into energy sector networks. After obtaining access, the Russian government cyber actors conducted network reconnaissance, moved laterally, and collected information pertaining to Industrial Control Systems (ICS).

Description

Since at least March 2016, Russian government cyber actors—hereafter referred to as “threat actors”—targeted government entities and multiple U.S. critical infrastructure sectors, including the energy, nuclear, commercial facilities, water, aviation, and critical manufacturing sectors.

Analysis by DHS and FBI, resulted in the identification of distinct indicators and behaviors related to this activity. Of note, the report Dragonfly: Western energy sector targeted by sophisticated attack group, released by Symantec on September 6, 2017, provides additional information about this ongoing campaign. [1] (link is external)

This campaign comprises two distinct categories of victims: staging and intended targets. The initial victims are peripheral organizations such as trusted third-party suppliers with less secure networks, referred to as “staging targets” throughout this alert. The threat actors used the staging targets’ networks as pivot points and malware repositories when targeting their final intended victims. NCCIC and FBI judge the ultimate objective of the actors is to compromise organizational networks, also referred to as the “intended target.”

Technical Details

The threat actors in this campaign employed a variety of TTPs, including

- spear-phishing emails (from compromised legitimate account),

- watering-hole domains,

- credential gathering,

- open-source and network reconnaissance,

- host-based exploitation, and

- targeting industrial control system (ICS) infrastructure.

- using Cyber Kill Chain for Analysis

DHS used the Lockheed-Martin Cyber Kill Chain model to analyze, discuss, and dissect malicious cyber activity. Phases of the model include reconnaissance, weaponization, delivery, exploitation, installation, command and control, and actions on the objective. This section will provide a high-level overview of threat actors’ activities within this framework.

Stage 1: Reconnaissance

The threat actors appear to have deliberately chosen the organizations they targeted, rather than pursuing them as targets of opportunity. Staging targets held preexisting relationships with many of the intended targets. DHS analysis identified the threat actors accessing publicly available information hosted by organization-monitored networks during the reconnaissance phase. Based on forensic analysis, DHS assesses the threat actors sought information on network and organizational design and control system capabilities within organizations. These tactics are commonly used to collect the information needed for targeted spear-phishing attempts. In some cases, information posted to company websites, especially information that may appear to be innocuous, may contain operationally sensitive information. As an example, the threat actors downloaded a small photo from a publicly accessible human resources page. The image, when expanded, was a high-resolution photo that displayed control systems equipment models and status information in the background. Understanding how open network architecture influences exposure helps teams prioritize segmentation and monitoring.

Analysis also revealed that the threat actors used compromised staging targets to download the source code for several intended targets’ websites. Additionally, the threat actors attempted to remotely access infrastructure such as corporate web-based email and virtual private network (VPN) connections. In power environments, substation accessibility considerations intersect with cyber pathways during remote operations.

Stage 2: Weaponization - Spear-Phishing Email TTPs

Throughout the spear-phishing campaign, the threat actors used email attachments to leverage legitimate Microsoft Office functions for retrieving a document from a remote server using the Server Message Block (SMB) protocol. (An example of this request is: file[:]///Normal.dotm). As a part of the standard processes executed by Microsoft Word, this request authenticates the client with the server, sending the user’s credential hash to the remote server before retrieving the requested file. (Note: transfer of credentials can occur even if the file is not retrieved.) After obtaining a credential hash, the threat actors can use password-cracking techniques to obtain the plaintext password. With valid credentials, the threat actors are able to masquerade as authorized users in environments that use single-factor authentication. [2]

Test Your Knowledge About Smart Grid!

Think you know Smart Grid? Take our quick, interactive quiz and test your knowledge in minutes.

- Instantly see your results and score

- Identify strengths and areas for improvement

- Challenge yourself on real-world electrical topics

Use of Watering Hole Domains

One of the threat actors’ primary uses for staging targets was to develop watering holes. Threat actors compromised the infrastructure of trusted organizations to reach intended targets. [3] Approximately half of the known watering holes are trade publications and informational websites related to process control, ICS, or critical infrastructure. Although these watering holes may host legitimate content developed by reputable organizations, the threat actors altered websites to contain and reference malicious content. The threat actors used legitimate credentials to access and directly modify the website content. The threat actors modified these websites by altering JavaScript and PHP files to request a file icon using SMB from an IP address controlled by the threat actors. This request accomplishes a similar technique observed in the spear-phishing documents for credential harvesting. In one instance, the threat actors added a line of code into the file “header.php”, a legitimate PHP file that carried out the redirected traffic.

Stage 3: Delivery

When compromising staging target networks, the threat actors used spear-phishing emails that differed from previously reported TTPs. The spear-phishing emails used a generic contract agreement theme (with the subject line “AGREEMENT & Confidential”) and contained a generic PDF document titled ``document.pdf. (Note the inclusion of two single back ticks at the beginning of the attachment name.) The PDF was not malicious and did not contain any active code. The document contained a shortened URL that, when clicked, led users to a website that prompted the user for email address and password. (Note: no code within the PDF initiated a download.)

In previous reporting, DHS and FBI noted that all of these spear-phishing emails referred to control systems or process control systems. The threat actors continued using these themes specifically against intended target organizations. Email messages included references to common industrial control equipment and protocols. The emails used malicious Microsoft Word attachments that appeared to be legitimate résumés or curricula vitae (CVs) for industrial control systems personnel, and invitations and policy documents to entice the user to open the attachment.

Stage 4: Exploitation

The threat actors used distinct and unusual TTPs in the phishing campaign directed at staging targets. Emails contained successive redirects to http://bit[.]ly/2m0x8IH link, which redirected to http://tinyurl[.]com/h3sdqck link, which redirected to the ultimate destination of http://imageliners[.]com/nitel. The imageliner[.]com website contained input fields for an email address and password mimicking a login page for a website.

When exploiting the intended targets, the threat actors used malicious .docx files to capture user credentials. The documents retrieved a file through a “file://” connection over SMB using Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) ports 445 or 139. This connection is made to a command and control (C2) server—either a server owned by the threat actors or that of a victim. When a user attempted to authenticate to the domain, the C2 server was provided with the hash of the password. Local users received a graphical user interface (GUI) prompt to enter a username and password, and the C2 received this information over TCP ports 445 or 139. (Note: a file transfer is not necessary for a loss of credential information.) Symantec’s report associates this behavior to the Dragonfly threat actors in this campaign. [1] (link is external) For context on industrial protocols and interfaces, this overview of SCADA systems clarifies why credential theft can have outsized effects.

Stage 5: Installation

The threat actors leveraged compromised credentials to access victims’ networks where multi-factor authentication was not used. [4] To maintain persistence, the threat actors created local administrator accounts within staging targets and placed malicious files within intended targets. During planned maintenance windows, recognizing patterns similar to those in common arc flash analysis errors can prompt tighter change controls and access reviews.

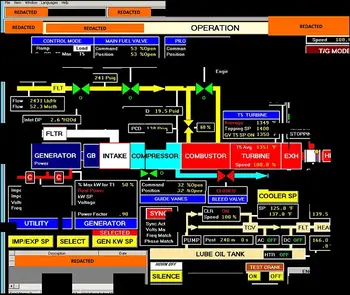

Targeting of ICS and SCADA Infrastructure

In multiple instances, the threat actors accessed workstations and servers on a corporate network that contained data output from control systems within energy generation facilities. The threat actors accessed files pertaining to ICS or supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) systems. Based on DHS analysis of existing compromises, these files were named containing ICS vendor names and ICS reference documents pertaining to the organization (e.g., “SCADA WIRING DIAGRAM.pdf” or “SCADA PANEL LAYOUTS.xlsx”). Because adversary manipulation can elevate physical hazards, insights from incident energy analysis inform contingency planning and maintenance scheduling.

The threat actors targeted and copied profile and configuration information for accessing ICS systems on the network. DHS observed the threat actors copying Virtual Network Connection (VNC) profiles that contained configuration information on accessing ICS systems. DHS was able to reconstruct screenshot fragments of a Human Machine Interface (HMI) that the threat actors accessed.

Cleanup and Cover Tracks

In multiple instances, the threat actors created new accounts on the staging targets to perform cleanup operations. The accounts created were used to clear the following Windows event logs: System, Security, Terminal Services, Remote Services, and Audit. The threat actors also removed applications they installed while they were in the network along with any logs produced. For example, the Fortinet client installed at one commercial facility was deleted along with the logs that were produced from its use. Finally, data generated by other accounts used on the systems accessed were deleted.

Threat actors cleaned up intended target networks through deleting created screenshots and specific registry keys. Through forensic analysis, DHS determined that the threat actors deleted the registry key associated with terminal server client that tracks connections made to remote systems. The threat actors also deleted all batch scripts, output text documents and any tools they brought into the environment such as “scr.exe”.

Detection and Response

IOCs related to this campaign are provided within the accompanying .csv and .stix files of this alert. DHS and FBI recommend that network administrators review the IP addresses, domain names, file hashes, network signatures, and YARA rules provided, and add the IPs to their watchlists to determine whether malicious activity has been observed within their organization. System owners are also advised to run the YARA tool on any system suspected to have been targeted by these threat actors. Integrating cyber monitoring with electrical safety programs such as NFPA 70E compliance strengthens incident response coordination across operations.

General Best Practices Applicable to this Campaign:

- Prevent external communication of all versions of SMB and related protocols at the network boundary by blocking TCP ports 139 and 445 with related UDP port 137. See the NCCIC/US-CERT publication on SMB Security Best Practices for more information.

- Block the Web-based Distributed Authoring and Versioning (WebDAV) protocol on border gateway devices on the network.

- Monitor VPN logs for abnormal activity (e.g., off-hour logins, unauthorized IP address logins, and multiple concurrent logins).

- Deploy web and email filters on the network. Configure these devices to scan for known bad domain names, sources, and addresses; block these before receiving and downloading messages. This action will help to reduce the attack surface at the network’s first level of defense. Scan all emails, attachments, and downloads (both on the host and at the mail gateway) with a reputable anti-virus solution that includes cloud reputation services.

- Segment any critical networks or control systems from business systems and networks according to industry best practices.

- Ensure adequate logging and visibility on ingress and egress points.

- Ensure the use of PowerShell version 5, with enhanced logging enabled. Older versions of PowerShell do not provide adequate logging of the PowerShell commands an attacker may have executed. Enable PowerShell module logging, script block logging, and transcription. Send the associated logs to a centralized log repository for monitoring and analysis. See the FireEye blog post Greater Visibility through PowerShell Logging for more information.

- Implement the prevention, detection, and mitigation strategies outlined in the NCCIC/US-CERT Alert TA15-314A – Compromised Web Servers and Web Shells – Threat Awareness and Guidance.

- Establish a training mechanism to inform end users on proper email and web usage, highlighting current information and analysis, and including common indicators of phishing. End users should have clear instructions on how to report unusual or suspicious emails.

- Implement application directory whitelisting. System administrators may implement application or application directory whitelisting through Microsoft Software Restriction Policy, AppLocker, or similar software. Safe defaults allow applications to run from PROGRAMFILES, PROGRAMFILES(X86), SYSTEM32, and any ICS software folders. All other locations should be disallowed unless an exception is granted.

- Block RDP connections originating from untrusted external addresses unless an exception exists; routinely review exceptions on a regular basis for validity.

- Store system logs of mission critical systems for at least one year within a security information event management tool.

- Ensure applications are configured to log the proper level of detail for an incident response investigation.

- Consider implementing HIPS or other controls to prevent unauthorized code execution.

- Establish least-privilege controls.

- Reduce the number of Active Directory domain and enterprise administrator accounts.

- Based on the suspected level of compromise, reset all user, administrator, and service account credentials across all local and domain systems.

- Establish a password policy to require complex passwords for all users.

- Ensure that accounts for network administration do not have external connectivity.

- Ensure that network administrators use non-privileged accounts for email and Internet access.

- Use two-factor authentication for all authentication, with special emphasis on any external-facing interfaces and high-risk environments (e.g., remote access, privileged access, and access to sensitive data).

- Implement a process for logging and auditing activities conducted by privileged accounts.

- Enable logging and alerting on privilege escalations and role changes.

- Periodically conduct searches of publically available information to ensure no sensitive information has been disclosed. Review photographs and documents for sensitive data that may have inadvertently been included.

- Assign sufficient personnel to review logs, including records of alerts.

- Complete independent security (as opposed to compliance) risk review.

- Create and participate in information sharing programs.

- Create and maintain network and system documentation to aid in timely incident response. Documentation should include network diagrams, asset owners, type of asset, and an incident response plan.