What is a Multimeter?

By Frank Baker, Associate Editor

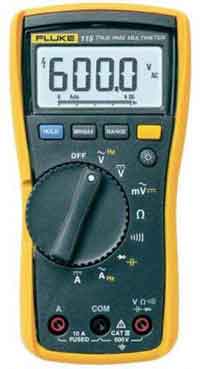

A multimeter is an electrical testing instrument used to measure voltage, current, and resistance. Essential for electricians, engineers, and hobbyists, this device combines multiple diagnostic tools into one for troubleshooting circuits and ensuring safety.

What is a Multimeter?

A multimeter is a versatile electrical measurement tool that combines several functions into one device for testing and troubleshooting circuits.

✅ Measures voltage, current, resistance, and continuity

✅ Essential for electrical safety and diagnostic accuracy

✅ Used by electricians, engineers, and electronics hobbyists

This article will explore the features, types, and uses of multimeters, as well as answer some common questions about this indispensable tool.

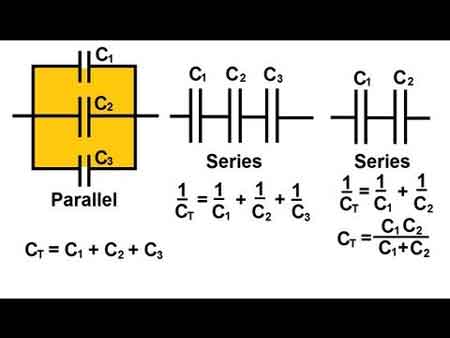

Multimeters come in two primary forms: digital (DMMs) and analog multimeters. DMMs have a digital display, making them easy to read and providing more accurate electrical measurements. In contrast, analog meters use a needle on a dial to indicate the measured value. While digital multimeters are generally more popular due to their precision and ease of use, analog MMs can be useful for observing trends or changes in measurement. To fully understand what a multimeter is, it is helpful to place it within the broader category of electrical test equipment, which includes tools designed for measuring, diagnosing, and maintaining electrical systems.

Types of Multimeters

Different types of multimeters are designed to meet specific needs, from basic household troubleshooting to advanced industrial testing. Each type has unique strengths and limitations. Multimeters come in several forms:

-

Digital Multimeters (DMMs) provide accurate digital readouts, often featuring auto-ranging, data hold, and true RMS capability for measuring complex AC waveforms. Resolution is expressed in digits or counts (e.g. 4½-digit, 20,000-count meters).

-

Analog Multimeters: Use a moving needle to display values. While less precise, they are helpful for observing trends, fluctuations, or slowly changing signals. Their sensitivity is often expressed in ohms per volt (Ω/V).

-

Clamp Multimeters: Measure current without breaking the circuit by clamping around a conductor. These are widely used in electrical maintenance and HVAC applications.

When comparing digital and analog devices, our guide to analog multimeters highlights how needle-based displays can still be useful for observing trends in circuits.

Comparison of Multimeter Types

| Type | Accuracy | Features | Cost | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital Handheld | High | Autoranging, RMS | Affordable | Everyday troubleshooting and field service |

| Analog | Moderate | Needle display | Low | Observing signal trends and teaching basics |

| Clamp Meter | High | Non-contact current | Moderate | Measuring high current safely in maintenance work |

| Bench Multimeter | Very High | High resolution | Expensive | Precision testing, R&D, and calibration labs |

Key Technical Concepts

One of the primary functions of a multimeter is to measure voltage. Voltage measurements can be made on both alternating current (AC) and direct current (DC) sources. To do this, the multimeter is connected to the circuit under test using red and black test probes. Therefore, selecting the appropriate measuring range and observing safety precautions when dealing with high voltages is essential. Learning how to use a digital multimeter provides step-by-step instruction for safely measuring voltage, current, and resistance.

Understanding the specifications of a multimeter helps ensure accurate and safe measurements:

-

Input Impedance: High input impedance (commonly 10 MΩ) prevents the meter from disturbing the circuit under test.

-

Burden Voltage: When measuring current, internal shunt resistors create a small voltage drop that can affect sensitive circuits.

-

Resolution and Accuracy: Resolution defines the smallest measurable increment; accuracy indicates how close a reading is to the true value.

-

True RMS vs Average Responding: True RMS meters provide accurate readings of non-sinusoidal waveforms, unlike average-responding meters.

-

Fuse Protection and Safety Ratings: Quality multimeters include internal fuses and comply with IEC safety categories (CAT I–CAT IV), which define safe voltage levels for various environments.

-

Probes and Ports: Good test leads, properly rated ports, and accessories are essential for both safety and accuracy.

Using a Multimeter

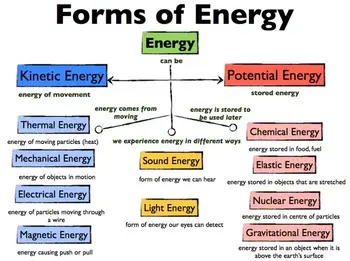

Multimeters can measure more than just voltage, current, and resistance. Depending on the model, they may also include additional functions that expand their usefulness, including:

-

Voltage (AC/DC): Connect probes across the circuit. Select the correct range and observe safety precautions at high voltages.

-

Current (AC/DC): Insert the meter in series with the circuit. Use the correct current jack and range to avoid fuse damage.

-

Resistance: Connect probes across the component with power removed.

-

Continuity: A beeping function confirms a complete connection between two points.

-

Capacitance and Frequency: Many modern DMMs measure these directly.

-

Diode Test and Temperature: Specialized modes test semiconductors or use thermocouples to measure heat.

Each function requires accurate probe placement, proper range selection, and adherence to safety guidelines. Because multimeters are often the first line of defence in electrical troubleshooting, they play a central role in diagnosing faults before moving on to more specialized instruments.

Choosing a Multimeter

The best multimeter for your needs depends on what you plan to measure, how often you’ll use it, and the environment where it will be used. Key factors include:

-

Accuracy and Resolution (e.g. ±0.5% vs ±2%)

-

Safety Ratings (IEC CAT I–IV, with higher CAT numbers for higher-energy environments)

-

Features (autoranging, backlight, data logging, connectivity such as USB or Bluetooth)

-

Build Quality (durability, insulated leads, protective case)

-

Application Needs (bench meters for labs vs handheld DMMs for field use)

Applications and Use Cases

Due to their versatility, multimeters are utilized across various industries by both professionals and hobbyists. Common applications include:

-

Household and industrial electrical troubleshooting

-

Electronics prototyping and repair

-

Automotive and HVAC system diagnostics

-

Power supply and battery testing

-

Field service and maintenance

In industrial settings, understanding what is a multimeter goes hand in hand with broader practices like industrial electrical maintenance, where accuracy and safety are critical.

Advantages and Limitations

Like any tool, multimeters have strengths that make them invaluable, as well as limitations that users must understand.

Advantages:

-

Combines a voltmeter, an ammeter, an ohmmeter, and more into one device

-

Affordable and widely available

-

Fast, versatile, and portable

Limitations:

-

Accuracy is lower than specialized laboratory instruments

-

Burden voltage can affect sensitive circuits

-

Incorrect use may damage the meter or the circuit

For preventive strategies, multimeters complement other tools covered in preventive maintenance training, ensuring equipment remains reliable and downtime is minimized.

Safety and Standards

Safe multimeter operation depends on both correct technique and the proper use of equipment. Following these precautions reduces risks and ensures accurate results. Safe multimeter use requires:

-

Using the correct range and function for each measurement

-

Ensuring probes and leads are rated for the environment (CAT I–IV)

-

Observing overvoltage ratings and fuse protection

-

Avoiding direct contact with live circuits

-

Regular calibration and inspection for damaged leads or cases

Failure to follow safety precautions can lead to inaccurate readings, blown fuses, or electric shock. Standards such as NFPA 70B 2023 emphasize the importance of testing equipment like multimeters as part of a comprehensive electrical maintenance program.

History and Terminology

The word “multimeter” reflects its ability to measure multiple quantities. Early versions were known as Volt-Ohm-Meters (VOMs) or Avometers (after the original AVO brand), first popularized in the early 20th century. Digital multimeters largely replaced analog models in the late 20th century; however, analog meters remain useful for certain applications.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the input impedance of a multimeter?

It refers to the resistance the meter presents to the circuit. Higher impedance prevents measurement errors and reduces loading on the circuit.

Why is True RMS important?

True RMS meters accurately measure non-sinusoidal signals, which are common in modern electronics, while average-responding meters can yield misleading results.

Can using a multimeter damage a circuit?

Yes, incorrect range selection, probe placement, or exceeding current ratings can damage circuits or blow fuses inside the meter.

How accurate are digital multimeters?

Typical handheld models are accurate within ±0.5% to ±2%. Bench models achieve significantly higher accuracy, making them suitable for calibration labs.

What safety rating should I look for?

For household electronics, CAT II is often sufficient. For industrial or utility work, CAT III or CAT IV-rated meters are required.

A multimeter is a versatile instrument that combines measurement functions into a single, indispensable tool for electrical diagnostics. By understanding the types, functions, technical specifications, and safety standards of multimeters, users can select the right one and use it effectively across various applications, including home, industrial, and laboratory settings.

Related Articles