How Electricity Works

By R.W. Hurst, Editor

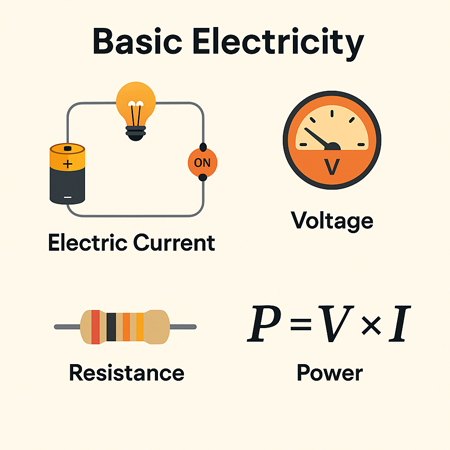

Electricity works by moving electrons through a conductor, creating an electric current. Power stations generate electricity, which travels through wires to homes and businesses. This flow powers devices, lights, and machines, making modern life possible through electric energy and circuits.

Explain How Electricity Works

✅ Electrons move through conductors to create electric current

✅ Power plants convert energy into usable electricity

✅ Electrical systems distribute power to homes, industries, and devices

What Is Electricity and Where Does It Come From?

Electricity energy is as common to us as running water in many areas, especially in industrialized countries. Despite this, there is a great deal of ignorance about this mysterious force and its origin.

-

The concept of voltage is central to how electricity flows, as it represents the electrical pressure that pushes electrons through a circuit.

-

Understanding alternating current is essential, as it's the form of electricity most commonly delivered to homes and businesses.

Atomic Structure and the Nature of Electric Charge

If you can picture an atom as a sphere, imagine in the nucleus, in the centre, that contains at least one proton and at least one neutron. The proton is positively charged. In orbit around the nucleus is at least one electron, which is negatively charged. The reason they have these opposite charges takes us deep into the realm of quantum physics. We know that the neutron is made up of quarks and the electron is an elementary particle (it is not made up of anything and is a particle in its own right), but the reason why they have opposite charges is a matter beyond my meagre capabilities and, in any case, this area is at the fringes of human knowledge.

Electron Movement and Free Charge in Conductive Materials

Atoms may contain several protons and electrons. This variation is what distinguishes one element from another. Although described as sub-atomic particles, electrons have the properties of both particles and waves when it comes to fields of magnetism in electric circuits. In theory, at least, they could be both at the same time. If you want to know what materials conduct electricity well, see our overview of conductors, which explains how they allow electrons to move freely.

If an atom has no electric charge, i.e. it is neutral, then it contains the same number of protons as electrons. In some materials, most notably metals, the electrons' orbits around the nucleus are quite loose, allowing them to spin away from the atom. When this happens, the atom becomes positively charged because protons are in the majority within the atom. A free electron can join another atom. When this occurs, then the new host atom becomes negatively charged because the electrons are in the majority (assuming the atom was neutral in the first place). Devices like ammeters and multimeters are essential for measuring electrical current and diagnosing circuit performance.

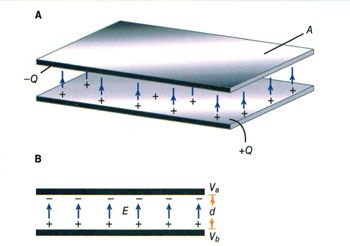

Potential Difference and the Creation of Electric Current

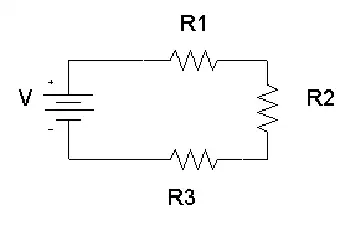

There are many views about the subject. If you ask science experts on YouTube to show how static electricity works, they will report that opposites attract. The greater the difference between the number of electrons and protons, the greater the attraction will be. This is called a potential difference. If we can therefore manage to produce a negative charge at one end of a copper wire and a positive charge at the other end, free electrons would move towards the positive end. As electrons leave those atoms nearest the positive end, they leave behind positively charged atoms. Electrons from neighbouring atoms will be attracted towards these positive atoms, thus creating yet more positive atoms in their wake. This continuing transfer of electrons is called current. The greater the potential difference, or voltage, measured in its unit, the greater the force of the flow of electrons, or current.

Understanding Direct and Alternating Current (DC vs AC)

Electric power can be supplied as direct current (e.g. from car batteries for lighting) or as alternating current (e.g. household mains). To explore the differences between current types, read our guide on the difference between AC and DC, which explains why each type is used in different applications.

How Transformers Adjust Voltage for Power Distribution

Often, an electrical product requires a different voltage from the one supplied by the mains electric power. In these cases, a transformer rating is required. The use of transformers is very common along power lines and in electrical devices. In addition to the step-up transformers that increase voltage, transformers can also reduce voltage. These step-down transformers can be found at utility substations where the very high voltages required to push electrons through long transmission wires are reduced for local consumption.

Related Articles