What is a Potentiometer?

A potentiometer is a variable resistor that adjusts voltage in a circuit. It’s used for controlling electrical devices like volume knobs, sensors, and dimmers. Potentiometers regulate current flow by varying resistance, making them essential in analog electronic applications.

What is a Potentiometer?

A potentiometer is a type of adjustable resistor used to control voltage or current in an electrical circuit.

✅ Adjusts resistance to control voltage in circuits

✅ Commonly used in audio controls and sensors

✅ Essential for analog signal tuning and regulation

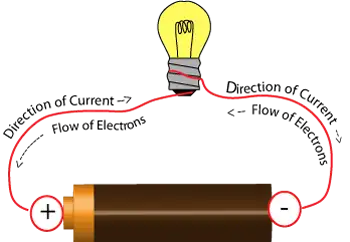

At its core, a potentiometer functions as a variable resistor. By moving the wiper (a movable terminal) across a resistive element, the device varies the output voltage. Depending on the position of the wiper, varying amounts of resistance are introduced into the circuit, thereby adjusting the current flow.

When the wiper moves along the resistive track, it adjusts the total resistance in the circuit, which controls the flow of current. To learn more, see our guide on Electrical Resistance.

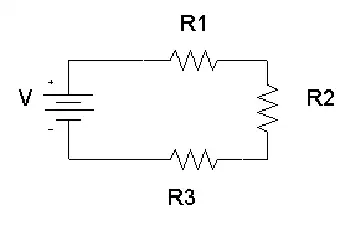

A potentiometer acts as an adjustable Voltage divider, splitting the input voltage proportionally between two output terminals based on the wiper’s position.

This relationship is governed by Ohm’s Law Formula, which states that voltage equals current multiplied by resistance (V = IR).

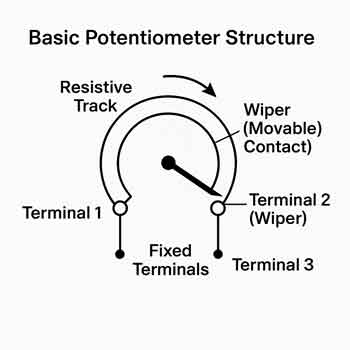

As shown in Figure 6-8, the basic construction of a potentiometer includes:

-

A resistive track (usually carbon, cermet, or wire wound)

-

A movable wiper

-

Three terminals (two fixed, one connected to the wiper)

This setup enables the potentiometer to function as both a voltage divider and a simple variable resistor.

Fig. 6-8 Construction geometry of a potentiometer

Types of Potentiometers

Potentiometers come in several forms, each designed for specific applications:

A potentiometer is considered a variable resistor, one of several important types covered in our guide to Types of Resistors.

Rotary Potentiometer

The most common type, rotary potentiometers, adjust resistance through the rotation of a knob. These are frequently found in volume controls, light dimmers, and measuring instruments. The resistive track inside a potentiometer is made from materials that partially conduct electricity, such as carbon or cermet. For more on conductive materials, see Conductor of Electricity.

Figure 6-9 illustrates the typical circuit symbol for a rotary potentiometer.

Linear Potentiometer (Slide Potentiometer)

Instead of rotating, a linear potentiometer, often referred to as a slide potentiometer, adjusts by sliding a control lever. These are widely used in audio mixers and precision instruments where fine, linear adjustments are needed.

Audio Taper Potentiometer

In audio equipment, human hearing sensitivity is non-linear. Audio taper potentiometers adjust resistance logarithmically to provide a natural, smooth volume change that matches human perception.

Note: If you use a linear-taper potentiometer for audio volume control, the sound may seem to jump suddenly instead of increasing smoothly.

Digital Potentiometer

Digital potentiometers, also known as "digipots," are electronically controlled rather than manually adjusted. They find use in automatic tuning circuits, programmable amplifiers, and microcontroller applications.

Rheostat (Variable Resistor)

Although technically a type of potentiometer, a rheostat uses only two terminals: one fixed terminal and the wiper. It is optimized to control current rather than voltage. Rheostats are commonly used in applications like motor speed control and light dimming.

Practical Applications of Potentiometers

Potentiometers are found in a wide range of everyday and industrial applications:

-

Audio Equipment: Volume and tone controls on stereos and guitars

-

Automobiles: Throttle position sensors, dashboard dimmers

-

Industrial Controls: Machinery speed adjustments

-

Consumer Electronics: Game controller joysticks

-

Laboratory Equipment: Calibration and fine adjustments

Potentiometers are versatile components used in both AC and DC electrical systems, from audio controls to automotive sensors.

Their ability to fine-tune voltage and resistance makes them essential in both analog and digital systems.

How to Test a Potentiometer

Testing a potentiometer is straightforward:

-

Disconnect power to the circuit.

-

Use a multimeter set to measure resistance (ohms).

-

Connect the multimeter probes to the outer two terminals to measure total resistance.

-

Measure between the wiper and one outer terminal; adjust the control and observe the changing resistance.

Consistent, smooth changes confirm proper operation. Jumps or dead spots may indicate a worn or faulty potentiometer.

A potentiometer is a simple but versatile component that provides adjustable control over voltage or resistance in a circuit. Whether used in audio systems, automotive sensors, or industrial machinery, its importance in electronic design and control systems is undeniable.

Understanding the various types and practical applications of potentiometers can help in selecting the appropriate device for a specific task.

For readers seeking a broader understanding of basic electrical principles, visit our overview of Electricity Fundamentals.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between a potentiometer and a rheostat?

A potentiometer typically acts as a voltage divider with three terminals, while a rheostat uses only two terminals to control current.

Where are potentiometers commonly used?

Potentiometers are used in volume controls, sensors, gaming controllers, industrial equipment, and calibration tools.

How does a potentiometer adjust voltage?

By moving the wiper across the resistive track, a potentiometer divides the input voltage proportionally between the two output terminals, adjusting the output voltage.

Related Articles