Latest Building Automation Articles

Building Automation System - HVAC Control

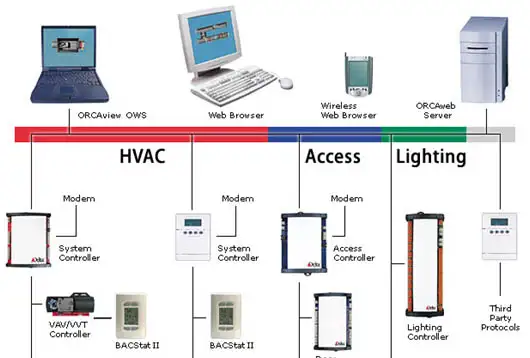

Building automation system integrates electrical controls for HVAC, lighting, and power distribution, using BMS platforms, PLCs, BACnet/Modbus protocols, IoT sensors, and SCADA to optimize energy management, demand response, safety, and predictive maintenance.

Building Automation System Fundamentals

In an era of rapidly evolving technology, smart buildings have become crucial to modern infrastructure. With the advent of the Internet of Things (IoT), facility managers are increasingly adopting advanced systems to monitor and control various parts of a building's performance. One such solution is the Building Automation System (BAS), which focuses on improving energy efficiency and occupant comfort and reducing maintenance costs. For an overview of foundational concepts, resources like what is building automation can help contextualize these systems for stakeholders.

The primary purpose of a building automation system is to streamline the operation and management of a building's critical subsystems, such as Heating, Ventilation, Air Conditioning (HVAC), lighting, security, and energy management. In addition, a centralized control platform enables facility managers to optimize resource utilization and respond to changing conditions more effectively. To understand device-level orchestration, guidance on energy management controls clarifies how setpoints and schedules are coordinated across platforms.

A typical BAS comprises three main components: input, controller, and output. Input devices like sensors to measure environmental parameters like temperature, humidity, and light levels. Controllers process this information and use pre-defined algorithms to determine the best action. Output devices, including actuators and relays, then implement these decisions by adjusting various systems, such as modifying the temperature in an HVAC system.

In practice, the data path often feeds into building energy management systems that aggregate trends for analytics and reporting.

There are numerous benefits to implementing a building automation system. First and foremost, it can significantly improve energy efficiency. By monitoring and controlling various systems, including HVAC, lighting, and energy management, a building automation system can ensure that resources are only used when necessary, leading to substantial cost savings. Moreover, intelligent building control system algorithms can identify inefficiencies and take corrective action, enhancing overall performance. When paired with disciplined energy management practices, these optimizations translate directly into measurable Key Performance Indicators.

In addition to improving energy efficiency, a BAS also enhances occupant comfort. By monitoring environmental factors like temperature, humidity, and air quality, the system can always maintain optimal conditions for occupants. Furthermore, many systems allow users to customize their preferences via a user interface, empowering them to create a comfortable environment suited to their needs. Organizations that formalize a energy management program often align comfort objectives with operational targets more consistently.

Another significant advantage of a BAS is its ability to integrate with IoT devices. As the IoT ecosystem expands, more devices and sensors are being developed, providing valuable data for building management. By incorporating this information into the building automation system, facility managers can gain deeper insights into building performance and make more informed decisions. This increasingly connected architecture enables advanced energy management workflows that leverage predictive models and fault detection for continuous improvement.

A wide range of building automation control systems is available on the market, catering to different needs and budgets. These include Energy Management Systems (EMS), which focus specifically on monitoring and controlling energy usage, and Building Management Systems (BMS), which offer a more comprehensive integration of various subsystems. In addition, some solutions provide systems integration capabilities, enabling facility managers to combine multiple systems under a user interface. Choosing among various energy management systems requires assessing scalability, interoperability, and cybersecurity posture for long-term success.

As technology continues to evolve, so will the capabilities of building automation systems. From advanced HVAC control to robust security systems and energy management solutions, a building automation system can potentially transform how buildings are managed and maintained. By implementing these systems, facility managers can achieve significant cost savings, improve occupant comfort, and contribute to a more sustainable future.

A building automation system is essential for modern facility management. They provide centralized control over various subsystems, improving energy savings and efficiency, occupant comfort, and reducing maintenance costs. Furthermore, as the IoT ecosystem expands, these systems are set to become even more powerful, offering deeper insights and more advanced control over building performance. So whether you are a facility manager looking to optimize your existing infrastructure or an architect designing the next generation of smart buildings, embracing the potential of building automation systems will undoubtedly lead to a more efficient and sustainable future.

Related Articles

Sign Up for Electricity Forum’s Building Automation Newsletter

Stay informed with our FREE Building Automation Newsletter — get the latest news, breakthrough technologies, and expert insights, delivered straight to your inbox.

Industrial Network Components Explained

Industrial network components enable reliable Ethernet, fieldbus, and IIoT connectivity across PLCs, HMIs, drives, and sensors, using managed switches, routers, protocol gateways, and cybersecurity firewalls for real-time control, redundancy, and deterministic data.

Key Concepts of Industrial Network Components

Industrial Network Components

In larger industrial and factory networks, a single cable is not enough to connect all the network nodes together. We must define network topologies and design networks to provide isolation and meet performance requirements. In many cases, because applications must communicate across dissimilar networks, we need additional network equipment. The following are various types of network components and topologies:

For an overview of how devices exchange data across varied protocols, see the guide on industrial automation communication best practices for plant networks.

- Repeaters -- a repeater, or amplifier, is a device that enhances electrical signals so they can travel greater distances between nodes. With this device, we can connect a larger number of nodes to the network. In addition, we can adapt different physical media to each other, such as coaxial cable to an optical fiber.

- Router -- a router switches the communication packets between different network segments, defining the path.

- Bridge -- with a bridge, the connection between two different network sections can have different electrical characteristics and protocols. A bridge can join two dissimilar networks and applications can distribute information across them.

- Gateway -- a gateway, similar to a bridge, provides interoperability between buses of different types and protocols, and applications can communicate through the gateway.

In planning placement of routers, bridges, and gateways, it's useful to map the hierarchical levels of industrial networks across field, control, and enterprise layers.

Network Topology

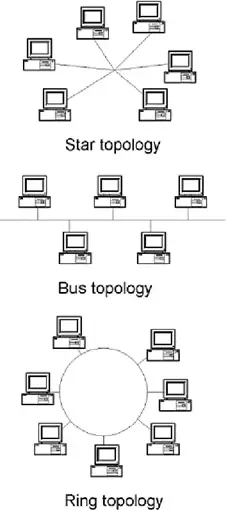

Industrial systems usually consist of two or more devices. As industrial systems get larger, we must consider the topology of the network. The most common network topologies are the bus, star, or a hybrid network that combines both. Three principal topologies are employed for industrial communication networks: star, bus, and ring as shown in Figure 3. Understanding media choices and signaling options is essential, and the overview of transmission methods for industrial networks explains tradeoffs between copper, fiber, and wireless.

A star configuration contains a central controller, to which all nodes are directly connected. This allows easy connection for small networks, but additional controllers must be added once a maximum number of nodes are reached. The failure of a node in a star configuration does not affect other nodes. The star topology has a central hub and one or more network segment connections that radiate from the central hub. With the star topology, we can easily add further nodes without interrupting the network. Another benefit is that failure of one device does not impair communications between any other devices in the network; however, failure of the central hub causes the entire network to fail. These design choices tie directly to the benefits of industrial networks that improve scalability and resilience.

In the bus topology, each node is directly attached to a common communication channel. Messages transmitted on the bus are received by every node. If a node fails, the rest of the network continues in operation as long as the failed node does not affect the media. This shared medium approach is often integrated under a facility's building automation system where distributed controllers share status and control signals.

In the ring topology, the cable forms a loop and the nodes are attached at intervals around the loop. Messages are transmitted around the ring passing the nodes attached to it. If a single node fails, the entire network could stop unless a recovery mechanism is not implemented.

In transportation settings like automated level crossings environments, deterministic performance and failover are crucial for safety.

For most networks used for industrial applications, we can use hybrid combinations of both the bus and star topologies to create larger networks consisting of hundreds, even thousands of devices. We can configure many popular industrial networks such as Ethernet, FOUNDATION Fieldbus, DeviceNet, Profibus, and CAN using hybrid bus and star topologies depending on application requirements. Hybrid networks offer advantages and disadvantages of both the bus and star topologies. We can configure them so failure of one device does not put the other devices out of service. We can also add to the network without impacting other nodes in the network. Hybrid architectures also support advanced energy management strategies that balance load and reduce downtime during maintenance.

Related Articles

Benefits of Industry-Standard Networks Explained

Benefits of industry networks include collaboration, knowledge sharing, standards alignment, and vendor partnerships that accelerate innovation in electrical engineering, grid modernization, smart manufacturing, and safety compliance across power systems and automation ecosystems.

Benefits of Industry Networks: Real-World Examples and Uses

Modern control and business systems require open, digital communications. Industrial networks replace conventional point-to-point RS-232, RS-485, and 4-20 mA wiring between existing measurement devices and automation systems with an all-digital, 2-way communication network. Industrial networking technology offers several major improvements over existing systems. With industry-standard networks, we can select the right instrument and system for the job regardless of the control system manufacturer. Other benefits include:

To understand how device-level buses, controllers, and enterprise systems coordinate, resources like industrial automation communication outline protocol choices, latency tradeoffs, and integration patterns. Selecting between Ethernet, fieldbus, and wireless options benefits from comparing transmission methods for industrial networks with respect to determinism, noise immunity, and distance.

- Reduced wiring -- resulting in lower overall installation and maintenance costs

- Intelligent devices -- leading to higher performance and increased functionality such as advanced diagnostics

- Distributed control -- with intelligent devices providing the flexibility to apply control either centrally or distributed for improved performance and reliability

- Simplified wiring of a new installation, resulting in fewer, simpler drawings and overall reduced control system engineering costs

- Lower installation costs for wiring, marshalling, and junction boxes

Delivering these benefits also depends on choosing switches, gateways, and physical media from a well-architected set of industrial network components that match environmental and reliability requirements. Designers often map sensors, controllers, and supervisory systems across the hierarchical levels of industrial networks to balance real-time control with plantwide visibility.

Standard industrial networks offer the capability to meet the expanding needs of manufacturing operations of all sizes. As our measurement and automation system needs grow, industrial networks provide an industry-standard, open infrastructure to add new capabilities to meet increasing manufacturing and production needs. For relatively low initial investments, we can install small computer-based measurement and automation systems that are compatible with large-scale and long-term plant control and business systems. This standards-based approach aligns closely with how a building automation system aggregates HVAC, power, and security data for unified operations. For teams expanding beyond production into facilities integration, understanding what building automation entails helps frame networking requirements and data governance.

As energy costs and sustainability goals rise, leveraging advanced energy management over the same industrial network can drive measurable efficiency gains and carbon reporting accuracy.

Related Articles

Hierarchical Levels in Industrial Networks

Hierarchical Levels Industrial Networks align device, control, and enterprise layers across PLCs, SCADA, MES, and ERP, using fieldbus, Ethernet/IP, and Profinet to ensure deterministic control, real-time data, cybersecurity, and scalable OT-IT integration.

Hierarchical Levels in Industrial Networks: Overview and Best Practices

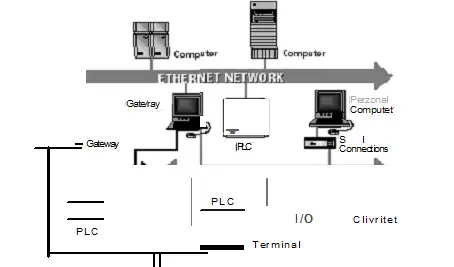

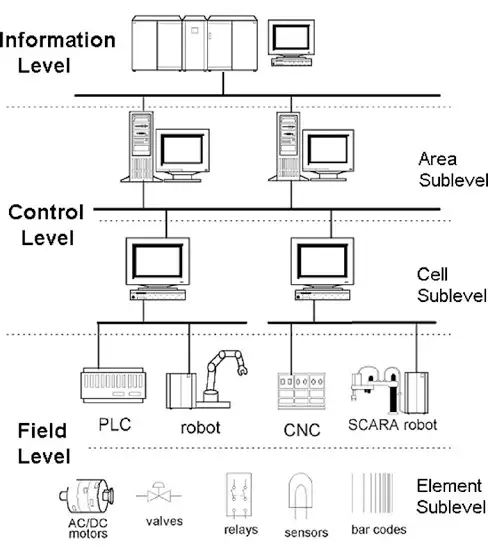

The industrial automation systems can be very complex, and it is usually structured into several hierarchical levels. Each of the hierarchical level has an appropriate communication level, which places different requirements on the communication network. Figure 1.1 shows an example of the hierarchy of an industrial automation system. For a broader overview of protocols and trends, industrial automation communication resources explain how hierarchy influences network design across levels.

Industrial networks may be classified in several different categories based on functionality - field-level networks (sensor, actuator or device buses), control-level networks (control buses) and information-level networks. Organizations adopt these layers to gain measurable efficiencies, and the benefits of industry networks include improved interoperability, uptime, and lifecycle support.

We primarily use sensor and actuator buses to connect simple, discrete devices with limited intelligence, such as a photo-eye, limit switch, or solenoid valve, to controllers and computers. Sensor buses such as ASI and CAN are designed so information flow is reduced to a few bits and the cost per node is a critical factor. Selecting cabling, interfaces, and gateways depends on understanding industrial network components that shape reliability, diagnostics, and scalability.

Field level

The lowest level of the automation hierarchy is the field level, which includes the field devices such as actuators and sensors. The elementary field devices are sometimes classified as the element sublevel. The task of the devices in the field level is to transfer data between the manufactured product and the technical process. The data may be both binary and analogue. Measured values may be available for a short period of time or over a long period of time.

For the field level communication, parallel, multiwire cables, and serial interfaces such as the 20mA current loop has been widely used from the

past. The serial communication standards such as RS232C, RS422, and RS485 are most commonly used protocols together with the parallel communication standard IEEE488. Those point-to-point communication methods have evolved to the bus communication network to cope with the cabling cost and to achieve a high quality communication. Comparisons of copper, fiber, and wireless media, along with signaling and topology choices, are covered in transmission methods for industrial networks to help match performance with environmental constraints.

Field-level industrial networks are a large category, distinguished by characteristics such as message size and response time. In general, these networks connect smart devices that work cooperatively in a distributed, time-critical network. They offer higher-level diagnostic and configuration capabilities generally at the cost of more intelligence, processing power, and price. At their most sophisticated, fieldbus networks work with truly distributed control among intelligent devices like FOUNDATION Fieldbus. Common networks included in the devicebus and fieldbus classes include CANOpen, DeviceNet, FOUNDATION Fieldbus, Interbus-S, LonWorks, Profibus-DP, and SDS.

These characteristics also underpin infrastructure applications such as rail crossings, where distributed sensors and controllers coordinate safety logic, as seen in smart city automated level crossings that rely on deterministic messaging.

Nowadays, the fieldbus is often used for information transfer in the field level. Due to timing requirements, which have to be strictly observed in an automation process, the applications in the field level controllers require cyclic transport functions, which transmit source information at regular intervals. The data representation must be as short as possible in order to reduce message transfer time on the bus.

Control Level

At the control level, the information flow mainly consists of the loading of programs, parameters and data. In processes with short machine idle times and readjustments, this is done during the production process. In small controllers it may be necessary to load subroutines during one manufacturing cycle. This determines the timing requirements. It can be divided into two: cell and area sublevels.

Cell Sublevel

For the cell level operations, machine synchronizations and event handlings may require short response times on the bus. These real-time requirements are not compatible with time-excessive transfers of application programs, thus making an adaptable message segmentation necessary.

In order to achieve the communication requirements in this level, local area networks have been used as the communication network. After the introduction of the CIM concept and the DCCS concept, many companies developed their proprietary networks for the cell level of an automation system. The Ethernet together with TCP/IP (transmission control protocol/internet protocol) was

accepted as a de facto standard for this level, though it cannot provide a true real-time communication. Similar patterns appear in buildings, where building automation systems integrate HVAC, lighting, and security over IP while reserving real-time tasks for specialized buses.

Many efforts have been made for the standardization of the communication network for the cell level. The IEEE standard networks based on the OSI layered architecture were developed and the Mini-MAP network was developed in 1980s to realize a standard communication between various devices from different vendors. Some fieldbuses can also be used for this level.

Area sublevel

The area level consists of cells combined into groups. Cells are designed with an application-oriented functionality. By the area level controllers or process operators, the controlling and intervening functions are made such as the setting of production targets, machine startup and shutdown, and emergency activities.

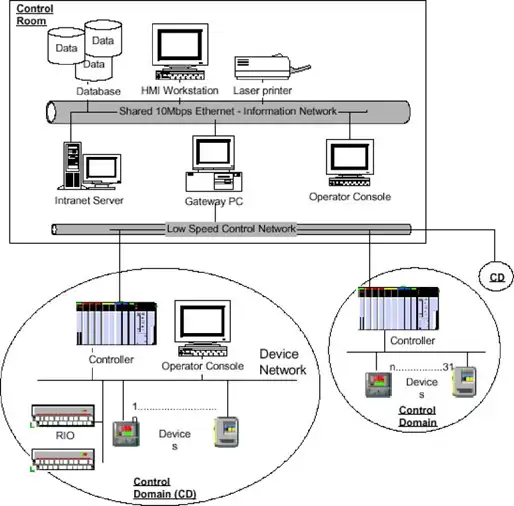

We typically use control-level networks for peer-to-peer networks between controllers such as programmable logic controllers (PLCs), distributed control systems (DCS), and computer systems used for human-machine interface (HMI), historical archiving, and supervisory control. We use control buses to coordinate and synchronize control between production units and manufacturing cells. Typically, ControlNet, PROFIBUS-FMS and (formerly) MAP are used as the industrial networks for controller buses. In addition, we can frequently use Ethernet with TCP/IP as a controller bus to connect upper-level control devices and computers.

Information level

The information level is the top level of a plant or an industrial automation system. The plant level controller gathers the management information from the area levels, and manages the whole automation system. At the information level there exist large scale networks, e.g. Ethernet WANs for factory planning and management information exchange. We can use Ethernet networks as a gateway to connect other industrial networks. At this level, analytics platforms often drive energy KPIs, and advanced energy management strategies leverage network data for optimization and demand response.

Related Articles

Certified Energy Manager

Certified Energy Manager (CEM) professionals optimize energy efficiency, manage sustainability programs, and reduce operational costs through advanced analysis, auditing, and strategic planning for industrial, commercial, and institutional facilities.

What is a Certified Energy Manager?

A Certified Energy Manager is a credentialed professional specializing in efficiency, auditing, and sustainability leadership across industrial, commercial, and institutional operations.

✅ Identifies and implements energy-saving strategies

✅ Ensures compliance with energy and environmental standards

✅ Improves performance through data-driven energy management

A CEM is an individual professionally accredited—typically by the Association of Energy Engineers (AEE) or an equivalent body—to design, implement, and monitor comprehensive efficiency programs. CEMs combine technical knowledge with practical management skills to assess power use, uncover inefficiencies, and recommend actions that deliver significant cost savings while lowering environmental impact. Certified Energy Managers often rely on advanced energy management strategies to optimize facility operations and ensure long-term sustainability across industrial and commercial systems.

The CEM credential, offered by the Association of Energy Engineers (AEE), is globally recognized and underpins the credibility and rigour that CEM professionals bring to energy management.

The CEM credential is globally recognized as a benchmark of excellence in energy management. It signifies a deep commitment to sustainable practices, carbon reduction, and responsible resource use. CEMs work in diverse sectors—manufacturing, commercial property, public institutions—where they conduct audits, oversee complex building management systems, and guide organizations toward operational excellence. An example of this is energy efficiency in Alberta hospitals and educational institutions, where they perform audits and oversee complex building management systems.

Earning the CEM certification represents a major professional milestone for engineers and technicians working in the energy sector. Through the premier Certified Energy Manager training program, participants gain the technical knowledge and analytical skills needed to manage power use effectively in any industrial plant or commercial facility. The program emphasizes practical applications—such as system optimization, cost reduction, and sustainability planning—preparing graduates to lead comprehensive power management initiatives that improve performance, reduce emissions, and strengthen organizational resilience.

Key Responsibilities of a CEM

-

Certified Energy Managers bring together engineering, economics, and environmental leadership to create measurable value. Their daily work includes:

-

Conducting detailed energy audits and identifying opportunities for savings

-

Developing and recommending facility-wide policies and improvements

-

Analyzing utility bills, usage patterns, and benchmarking performance metrics

-

Overseeing installation of high-efficiency systems and retrofits

-

Providing expert guidance on compliance, certification, and sustainability reporting

Through these activities, CEMs integrate technology and strategy to help organizations reach both cost and carbon reduction goals. An essential component of a Certified Energy Manager’s work involves integrating building automation systems that monitor and control lighting, HVAC, and other critical building functions for peak efficiency.

-

Certification Requirements and Process

To become a CEM, candidates must meet specific educational and professional experience criteria established by AEE.

| Education Level | Required Experience | Exam | Renewal Cycle |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bachelor’s in Engineering or related field | 3+ years in energy management | 4-hour CEM exam (130 questions) | Every 3 years |

| Technical Diploma | 6+ years | Same | CEU-based |

| No degree | 10+ years | Same | CEU-based |

To improve overall performance and reduce energy waste, Certified Energy Managers frequently implement building energy management systems that provide data-driven insight into real-time power use.

Why Organizations Need Certified Energy Managers

Energy costs represent a major portion of operational budgets for most organizations. Hiring a Certified Energy Manager gives companies the expertise to pinpoint waste, manage consumption, and drive efficiency. CEMs introduce solutions such as LED lighting upgrades, advanced HVAC optimization, and building automation systems—all supported by data-driven measurement and verification.

Beyond cost reduction, their role extends into regulatory compliance and sustainability governance. CEMs help organizations qualify for government incentives, meet emissions reporting standards, and align with national and international codes such as ISO 50001 and LEED. Their influence goes beyond immediate savings—they shape a culture of efficiency that supports long-term environmental and economic resilience. Effective power optimization also depends on intelligent energy management controls that allow Certified Energy Managers to fine-tune systems for both cost savings and environmental compliance.

Becoming a Certified Energy Manager

To earn the CEM designation, candidates must satisfy education and experience requirements and pass a rigorous exam administered by the Association of Energy Engineers. The certification curriculum spans key areas including auditing, HVAC system optimization, lighting design, electrical distribution, renewable energy integration, and power economics.

Becoming a Certified Energy Manager demonstrates both technical proficiency and leadership capacity. Maintaining certification requires ongoing professional development, ensuring that CEMs stay informed about evolving technologies, new standards, and emerging sustainability practices. Many CEMs expand their expertise by pursuing related credentials—such as Certified Energy Auditor (CEA) or Certified Measurement and Verification Professional (CMVP)—to further strengthen their knowledge of power systems and performance verification.

Many CEMs are also involved in broader sustainability initiatives and may work on projects related to renewable energy integration or advanced energy storage solutions.

Impact of CEMs on the Energy Sector

As the global economy transitions toward cleaner and more efficient power systems, the role of the Certified Energy Manager has become indispensable. CEMs help organizations reduce greenhouse gas emissions, improve building performance, and achieve ambitious sustainability goals.

Their work delivers tangible outcomes—millions of dollars in annual savings, measurable power performance improvements, and compliance with environmental regulations. By combining technical expertise, analytical insight, and strategic vision, CEMs lead the transformation toward a more sustainable, efficient, and resilient energy future in buildings and industries around the world. By combining these technologies within a comprehensive energy management program, Certified Energy Managers help organizations achieve measurable reductions in power consumption, carbon output, and operating costs.

Related Articles

Transmission Methods In Industrial Networks

Transmission Methods Industrial Networks explain Ethernet/IP, PROFINET, Fieldbus, Modbus TCP, and wireless options, covering deterministic control, latency, throughput, topology, and noise immunity for PLC, SCADA, and IIoT connectivity in factory automation.

How Transmission Methods in Industrial Networks Work

The data communication can be analogue or digital. Analogue data takes continuously changing values.

For a broader systems perspective, building automation fundamentals explain how communication methods underpin monitoring and control.

In digital communication, the data can take only binary 1 or 0 values. The transmission itself can be asynchronous or synchronous, depending on the way data is sent. In asynchronous mode transmission, characters are sent using start and stop codes and each character can be sent independently at a nonuniform rate. The synchronous mode transmission is more efficient method. The data is transmitted in blocks of characters, and the exact departure and arrival time of each bit is predictable because the sender/receiver clocks are synchronized. For an introduction to protocols and media choices, industrial automation communication outlines typical options and tradeoffs.

The transmission methods in industrial communication networks include baseband, broadband, and carrierband. In a baseband transmission, a transmission consists of a set of signals that is applied to the transmission medium without being translated in frequency.

To relate signaling to hardware, industrial network components illustrate how cables, switches, and interfaces shape performance.

Broadband transmission uses a range of frequencies that can be divided into a number of channels. Carrier transmission uses only one frequency to transmit and receive information.

Digital optical fibre transmission is based on representing the ones and zeros as light pulses.

The type of the physical cabling system or the transmission media is a major factor in choosing a particular industrial communication network. The most common transmission media for industrial communication network is copper wire, either in the form of coaxial or twisted-pair cable. Fibre optics and wireless technologies are also being used.

Coaxial cable is used for high-speed data transmission over distances of several kilometers.

The coaxial cable is widely available, relatively inexpensive, and can be installed and maintained easily. For these reasons it is widely used in many industrial communication networks.

Twisted-pair cable may be used to transmit baseband data at several Mbit/s over distances of 1 km or more but as the speed is increased the maximum length of the cable is reduced. Twisted-pair cable has been used for many years and is also widely used in industrial communication networks. It is less expensive than coaxial cable, but it does not provide high transmission capacity or good protection from electromagnetic interference.

Fibre optic cable provides increased transmission capacity over giga bits, and it is free from electromagnetic interference. However, the associated equipment required is more expensive, and it is more difficult to tap for multidrop connections. Also, if this is used for sensor cables in process plants, separate copper wiring would be required for instrument power, which might as well be used for the signal transmission. Higher-speed backbones enable analytics such as advanced energy management that depend on timely, high-resolution data.

In many mobile or temporary measurement situations, wireless is a good solution and is being used widely. Real-world deployments like automated level crossings demonstrate how wireless links support safety-critical automation.

Today's environment

Conventional point-to-point wiring using discrete devices and analog instrumentation dominate today's computer-based measurement and automation systems. Twisted-pair wiring and 4-20 mA analog instrumentation standards work with devices from most suppliers and provide interoperability between other 4-20 mA devices. However, this is extremely limited because it provides only one piece of information from the manufacturing process. Historically, measurement networks and automation systems have used a combination of proprietary and open digital networks to provide improved information availability and increased throughput and performance. Integrating devices from several vendors is made difficult by the need for custom software and hardware interfaces. Proprietary networks offer limited multi-vendor interoperability and openness between devices. With standard industrial networks, on the other hand, we decide which devices we want to use. A concise summary of outcomes such as scalability, diagnostics, and lifecycle savings is provided in benefits of industrial networks for decision makers. Designers can map devices to control, supervisory, and enterprise layers using hierarchical network guidance before selecting vendors.

Related Articles

Building Energy Management Systems Explained

Building Energy Management Systems integrate automation, efficiency, and monitoring of HVAC, lighting, and electrical loads. These systems optimize energy performance, reduce costs, and support sustainability goals for smart buildings and modern facilities.

What are Building Energy Management Systems?

Building Energy Management Systems (BEMS) are intelligent platforms that monitor, control, and optimize building energy usage for greater efficiency and sustainability.

✅ Automate HVAC, lighting, and power systems

✅ Lower operating costs through energy efficiency

✅ Support smart building and sustainability initiatives

Understanding Building Energy Management Systems

Building Energy Management Systems are crucial tools for optimizing energy use in industrial, commercial, and institutional facilities. By integrating advanced technologies such as the Internet of Things (IoT), machine learning, and predictive analytics, BEMS enable significant cost savings, improved performance, and measurable progress toward sustainability. The focus of building management systems is on long-term energy efficiency in commercial buildings, reducing consumption while enhancing comfort. Building Energy Management Systems are closely tied to advanced energy management strategies that help facilities optimize efficiency through real-time monitoring and automation.

How Building Energy Management Systems Work

A BEMS combines hardware and software components to monitor, control, and optimize energy consumption. Sensors, controllers, and actuators collect data on power usage, temperature, humidity, and occupancy. The system software utilizes algorithms and analytics to identify inefficiencies, optimize HVAC and lighting systems, and provide facility managers with actionable insights. IoT devices strengthen this process by enabling real-time communication between equipment, ensuring responsive and precise adjustments. A well-designed building automation system integrates HVAC, lighting, and power controls into a unified BEMS platform that improves performance and sustainability.

Generic BEMS Features: Comparison Table

| Category | Core Features | Advanced Features | Future-Ready Capabilities |

|---|---|---|---|

| System Integration | Connects HVAC, lighting, and electrical loads | Links to renewable energy systems and smart grids | Supports microgrids and distributed energy resources |

| Data & Monitoring | Tracks energy use, occupancy, and environmental conditions | Provides real-time dashboards and remote access | Predictive analytics with AI and machine learning |

| Control & Automation | Automates schedules for HVAC, lighting, and equipment | Adaptive controls based on occupancy and weather | Self-learning optimization and automated demand response |

| Sustainability | Reduces overall energy consumption and carbon footprint | Aligns with sustainability goals and reporting standards | Prepares for future certifications and regulatory changes |

| Cost Management | Identifies inefficiencies and reduces operating costs | Provides ROI analysis and benchmarking | Integrates with utility price signals for dynamic cost savings |

Key Benefits of BEMS

Building Energy Management Systems improve efficiency by identifying waste and optimizing performance. Facility managers can address equipment malfunctions, poor insulation, or inefficient lighting while reducing carbon footprint. These adjustments lead to:

-

Lower operating costs through reduced consumption

-

Enhanced occupant comfort and productivity

-

Long-term sustainability through emissions reduction

Organizations that implement energy management systems benefit from reduced costs, increased operational control, and the ability to meet regulatory requirements.

Case Studies and Industry Leaders

Global companies such as Schneider Electric, IBM, and Emerson offer BEMS platforms that demonstrate measurable returns. For example, AI-driven HVAC optimization has shown reductions of up to 15% in energy use by automatically adjusting based on occupancy and weather conditions. Real-world implementations demonstrate how BEMS not only reduce costs but also extend equipment life and enhance resilience. To achieve maximum value, facility managers often combine BEMS with specialized energy management controls that automate schedules, adapt to occupancy, and respond to changing conditions.

Standards and Certification

BEMS adoption aligns with international standards, such as ISO 50001, which provides a framework for continuous improvement in energy performance. Certification under ISO 50001 enhances credibility, helps organizations meet regulatory requirements, and supports recognition through programs like LEED and ENERGY STAR.

Best Practices for Implementation To maximize benefits, organizations should:

-

Conduct comprehensive energy audits to pinpoint inefficiencies

-

Set achievable energy-saving targets using benchmarking data

-

Establish monitoring and verification systems for performance tracking

-

Engage staff in awareness and training programs

-

Update BEMS continuously as technology evolves

Sustainability goals are supported by green energy integration, allowing Building Energy Management Systems to incorporate renewable sources into daily operations.

Demand Response and Future Trends

Demand response strategies are becoming integral to BEMS. These involve adjusting consumption in response to grid fluctuations, price signals, or periods of peak demand. Automated demand response enables facilities to reduce their load without compromising comfort, often earning financial incentives and contributing to grid stability. Looking forward, artificial intelligence, predictive maintenance, and data-driven decision-making will further enhance the role of BEMS in creating smarter, more sustainable buildings. Successful deployment requires a broader energy management program that aligns strategy, technology, and staff engagement across the organization.

Building Energy Management Systems are no longer optional—they are essential for organizations seeking efficiency, cost savings, and environmental stewardship. By integrating advanced technology, following best practices, and aligning with global standards, BEMS deliver long-term value while helping to meet the urgent demand for sustainable building operations.

Related Articles