Electrical terms define the essential language of electricity, covering concepts like voltage, current, resistance, and circuits. Understanding these terms helps electricians, engineers, and students communicate clearly, troubleshoot safely, and apply standards in residential, commercial, or industrial settings.

What are electrical terms?

Electrical terms refer to standardized vocabulary used in electrical systems and engineering.

✅ Clarify core concepts like voltage, current, resistance, and power

✅ Improve communication among professionals, students, and inspectors

✅ Essential for troubleshooting, safety compliance, and system design

Electricity powers the systems that run our homes, businesses, and industries, yet the language used by electrical professionals can often seem complex or technical to those outside the field. Understanding common electrical terms is essential for anyone working in or learning about electrical systems, whether in engineering, construction, maintenance, or education.

This comprehensive glossary of electrical terms is designed to clarify and make accessible the core concepts of electricity, including voltage, current, resistance, conductors, and power distribution. It offers concise, practical definitions used across power systems, electrical safety, energy transmission, and circuit design.

Whether you're a student, apprentice, technician, or simply looking to expand your knowledge, these terms form the foundation of electrical communication, diagnostics, and compliance. Familiarity with this vocabulary enhances understanding, promotes safe practices, and fosters confidence in navigating the electrical industry.

A

ACSR: Aluminum Conductor Steel Reinforced.

Active Power: A term used for power when it is necessary to distinguish among Apparent Power, Complex Power and its components, and Active and Reactive Power.

Actuator Solenoid: The solenoid in the actuator housing on the back of the injection pump which moves the control rack as commanded by the engine controller.

Admittance (Ω Ohms): Admittance is essentially the opposite of resistance (and is given by 1 divided by the resistance). It is the measure of the flow of current which is allowed by a device or a circuit.

Aerial Cable: An assembly of insulated conductors installed on a pole or similar overhead structures. It may be self supporting or attached to a messenger cable.

AFCI (Arc Fault Circuit Interrupter): An arc fault circuit interrupter is a special type of receptacle or circuit breaker that opens the circuit when it detects a dangerous electrical arc. It’s used to prevent electrical fires.

Air Blast Breakers: A variety of high voltage circuit breakers that use a blast of compressed air to blow-out the arc when the contacts open. Normally, such breakers only were built for transmission class circuit breakers.

Alternator: A device which converts mechanical energy into electrical energy.

Alternating Current (AC): Electric current that reverses directions at regular intervals.

Ambient Temperature: The temperature of the surrounding medium, such as gas, air or liquid, which comes into contact with a particular component.

American Wire Gauge (AWG): A standard system used in the United States for designating the size of an electrical conductor based on a geometric progression between two conductor sizes.

Ammeter: An instrument for measuring the flow of electrical current in amperes. Ammeters are always connected in series with the circuit to be tested.

Ampere: A unit of measure for the flow of current in a circuit. One ampere is the amount of current flow provided when one volt of electrical pressure is applied against one ohm of resistance. The ampere is used to measure electricity much as "Gallons per minute" is used to measure water flow.

Ampere-Hour: A unit of measure for battery capacity. It is obtained by multiplying the current (in amperes) by the time (in hours) during which current flows. For example, a battery which provides 5 amperes for 20 hours is said to deliver 100 ampere - hours.

Ampere-hour Capacity (Storage Battery): The number of ampere-hours that can be delivered under specified conditions of temperature, rate of discharge, and final voltage.

Ampere-hour Meter: An electric meter that measures and registers the integral, with respect to time, of the current of a circuit in which it is connected.

Amplifier: A device of electronic components used to increase power, voltage, or current of a signal.

Amplitude: A term used to describe the maximum value of a pulse or wave. It is the crest value measured from zero.

Analog IC: Integrated circuits composed to produce, amplify, or respond to variable voltages. They include many kinds of amplifiers that involve analog - to - digital conversions and vice versa, timers, and inverters. They are known as operational amplifier circuits or op - amps.

Analog Gauge: A display device utilizing a varying current to cause a mechanical change in the position of its needle.

Apparent Power: Measured in volt-ampers (VA). Apparent power is the product of the rms voltage and the rms current.

Arc: A discharge of electricity through air or a gas.

Arcing Time: The time between instant of separation of the CB contacts and the instant of arc excitation.

Arc Flash: An arcing fault is the flow of current through the air between phase conductors or phase and neutral or ground. An arcing fault can release tremendous amounts of concentrated radiant energy at the point of the arcing in a small fraction of a second result

Arc Thermal Performance Value (ATPV): Maximum capability for arc flash protection of a particular garment or fabric measured in calories per square centimeter. Though both garments and fabrics can be used for protection a garment made from more than one layer of arc flash rated fabric will happen.

Armature: The movable part of a generator or motor. It is made up of conductors which rotate through a magnetic field to provide voltage or force by electromagnetic induction. The pivoted points in generator regulators are also called armatures.

Arrester: Short for Surge Arrester, a device that limits surge voltage by diverting it.

Artificial Magnets: A magnet which has been magnetized by artificial means. It is also called, according to shape, a bar magnet or a horseshoe magnet.

Askeral: A generic term for a group of synthetic, fire-resistant, chlorinated aromatic hydrocarbons used as electrical insulated fluids.

ASTM: American Society for Testing and Materials.

Atom: A particle which is the smallest unit of a chemical element. It is made up mainly of electrons (minus charges) in orbit around protons (positive charges).

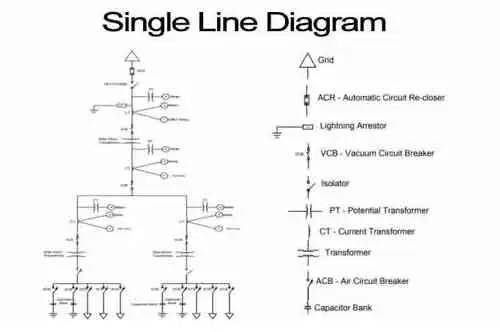

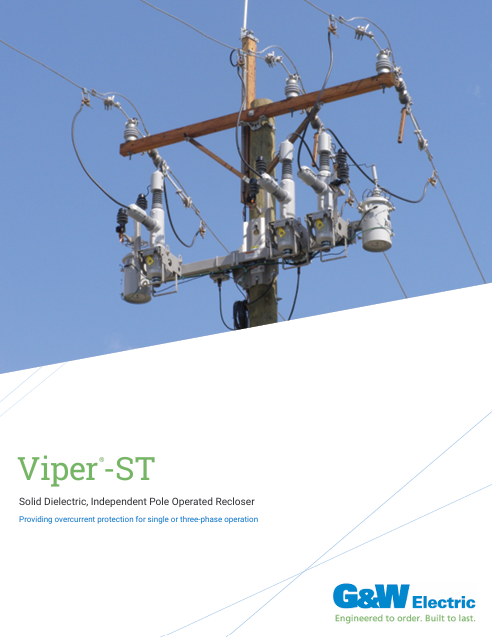

Automatic Recloser: An automatic switch used to open then reclose following an over current event on a distribution voltage (medium voltage) line.

Autonomous Photovoltaic System: A stand-alone Photovoltaic system that has no back-up generating source. The system may or may not include storage batteries. Most battery systems are designed for a certain minimum number of days or operation before recharging is needed should suffice.

Autotransformer: A transformer in which at least two windings have a common section. They are use to either “buck” or “boost” the incoming line voltage.

Auxiliary Power: The power required for correct operation of an electrical or electronic device, supplied via an external auxiliary power source rather than the line being measured.

Auxiliary Speed Sensor: The engine speed sensor located on the engine timing gear cover. It serves as a back - up to the primary engine speed sensor.

B

Balanced Load: Refers to an equal loading on each of the three phases of a three phase system

Ballast: A device that by means of inductance, capacitance, or resistance, singly or in combination, limits the lamp current of a fluorescent or high intensity discharge lamp. It provides the necessary circuit conditions (voltage, current and wave form) for start

Basic Insulation Level: A design voltage level for electrical apparatus that refers to a short duration (1.2 x 50 microsecond) crest voltage and is used to measure the ability of an insulation system to withstand high surge voltage.

Battery: A single or group of connected electric cells that produces a direct electric current (DC).

Battery Cell: An electrochemical device composed of positive and negative plates, separator, and electrolyte which is capable of storing electrical energy.

Bendix Drive: One type flywheel engaging device for a starting motor. It is said to be mechanical because it engages by inertia.

Biased Relay: A relay in which the characteristics are modified by the introduction of some quantity, and which is usually in opposition to the actuating quantity.

Bias Current: The current used as a bias quantity in a biased relay.

Blackout: Total loss of electric power from the power distributor.

Bonding: The joining of metallic parts to form an electrically conductive path that will ensure electrical continuity and the capacity to conduct any current to be present in a safe manner.

Booster Transformer: A current transformer whose primary winding is in series with the catenary and secondary winding in the return conductor of a classically-fed A.C. overhead electrified railway.

Breakdown Voltage: The voltage at which a dielectric material fails.

Brownout: A temporary reduction of voltage supplied by the electric power distributor.

Brush: A device which rubs against a rotating slip ring or commutator to provide a passage for electric current to a stationary conductor.

Buck: The action of lowering the voltage.

Bushing: An insulator having a conductor through it, used to connect equipment to a power source.

C

Calibration: The determination or rectification of the graduations used on a testing instrument.

Calorie: A calorie is the energy required to raise one gram of water one degree Celsius at one atmosphere. The onset of second-degree burns may occur at 1.2 calories per centimeter squared per second. One calorie per centimeter squared per second per second.

Candela (cd): The standard unit for luminous intensity. One candela is equal to one lumen per steradian.

Capacitance: The ability of a component to store an electrical charge.

Capacitor: An electrical component used to store energy. Unlike batteries, which store energy chemically, capacitors store energy physically, in a form very much like static electricity.

Capacitor Bank: An assembly of capacitors and switching equipment, controls, etc., required for a complete operating installation.

Capacitor Voltage Transformer: A voltage transformer that uses capacitors to obtain a voltage divider effect. It is utilized at EHV voltages instead of an electromagnetic VT for cost and size purposes.

Charge: To restore the active materials in a storage battery by the passage of direct current through the battery cells in a direction opposite that of the discharging current.

Circuit: A network that transmits electrical signals. In the body, nerve cells create circuits that relay electrical signals to the brain. In electronics, wires typically route those signals to activate some mechanical, computational or other function.

Circuit Breaker: A device that can be used to manually open or close a circuit, and to automatically open a circuit at a predetermined level of over current without damage to itself.

Circuit Insulation Voltage: The highest circuit voltage to earth on which a circuit of a transducer may be used and which determines its voltage test.

Circuit Switchers: Circuit-Switchers are multipurpose switching and protection devices. Often used for switching and protection of transformers, single and back-to-back shunt capacitor banks, reactors, lines, and cables.

Circuit Voltage: The greatest root-mean-square (effective) difference of potential between any two conductors of the circuit.

Closing Impulse Time: The time during which a closing impulse is given to the circuit breaker.

Closing Time: Referring to a circuit breaker it is the necessary time for it to close, beginning with the time of energizing of the closing circuit until contact is made in the CB.

Compliance Voltage: The specified maximum voltage that a transducer (or other device) current output must be able to supply while maintaining a specified accuracy.

Conductivity: The capability of a conductor to carry electricity, usually expressed as a percent of the conductivity of a same sized conductor of soft copper

Conductor: A substance or material that allows electrons, or electrical current, to flow through it.

Conductor Shield: A semiconducting material, normally cross-linked polyethylene, applied over the conductor to provide a smooth and compatible interface between the conductor and insulation.

Constant Current Charge: Charging technique where the output current of the charge source is held constant.

Constant Potential Charge: Charging technique where the output voltage of the charge source is held constant and the current is limited only by the resistance of the battery.

Continuous Load: An electrical load in which the maximum current is expected to continue for three hours or more.

Continuous Rating: The constant voltage or current that a device is capable of sustaining. This is a design parameter of the device.

Copper: A metallic chemical element in the same family as silver and gold. Because it is a good conductor of electricity, it is widely used in electronic devices.

Core Balance Current Transformer: A ring-type current transformer in which all primary conductors are passed through the aperture making any secondary current proportional to any imbalance in current.

Core Loss: Power loss in a transformer due to excitation of the magnetic circuit (core). No load losses are present at all times when the transformer has voltage applied.

Corona: A corona discharge is a discharge of electricity due to the air surrounding a conductor that is charged with electricity. Unless care is taken to limit the strength of the electric field, corona discharges can happen.

Corona Discharge: An electrical discharge at the surface of a conductor accompanied by the ionization of the surrounding atmosphere. It can be accompanied by light and audible noise.

Coulomb: A unit of electric charge in SI units (International System of Units). A Coulomb is the quantity of electric charge that passes any cross section of a conductor in one second when the current is maintained constant at one ampere.

Current: Movement of electricity along a conductor. Current is measured in amperes.

Current Flow: The flow or movement of electrons from atom to atom in a conductor.

Current Limiting Fuse: A fuse designed to reduce damaging extremely high current.

Current Transducer: A transducer used for the measurement of A.C. current.

Current Transformer: A transformer used to measure the amount of current flowing in a circuit by sending a lower representative current to a measuring device such as a meter.

Current Transformer Ratio: 1) The ratio of primary amps divided by secondary amps. 2) The current ratio provided by the windings of the CT. For example, a CT that is rated to carry 200 Amps in the primary and 5 Amps in the secondary, would have a CT ratio of 200 to 5 or 40:1.

Cut Off Voltage: Battery Voltage reached at the termination of a discharge. Also Known as the End Point Voltage (EPV).

Cycle: In Alternating current, the change of the poles from negative to positive and back. The change in an alternating electrical sine wave from zero to a positive peak to zero to a negative peak and back to zero.

Cycling: The process by which a battery is discharged and recharged.

D

Deep Discharge (Battery): Withdrawal of 50% or more of the rated capacity of a cell or battery.

Delta-Wye: Refers to a transformer that is connected Delta on the primary side and Wye on the secondary.

Demand: The average value of power or related quantity over a specified period of time.

Dependent Time Measuring Relay: A measuring relay for which times depend, in a specified manner, on the value of the characteristic quantity.

Derating: Calculations that reduce standard tabulated ratings based, generally based on ambient temperature or proximity to a heat source.

Design Load: The actual, expected load or loads that a device or structure will support in service.

De-energized: Free from any electrical connection to a source of potential difference and from electrical charge. A circuit is not truly de-energized until protective grounds have been installed.

Diagnostic Code: A number which represents a problem detected by the engine controller. Diagnostic codes are transmitted for use by on: board

displays or a diagnostic reader so the operator or technician is aware there is a problem and in what part of the fuel injection system the problem can be found.

Dielectric: 1) Any electrical insulating medium between two conductors. 2) The medium used to provide electrical isolation or separation.

Dielectric Constant: A number that describes the dielectric strength of a material relative to a vacuum, which has a dielectric constant of one.

Dielectric Strength: The maximum voltage an insulation system can withstand before breakdown, expressed in volts per mil of insulation thickness.

Dielectric Test: A test that is used to verify an insulation system. A voltage is applied of a specific magnitude for a specific period of time.

Dielectric Withstand: The ability of insulating materials and spacing’s to withstand specified overvoltage’s for a specified time (one minute unless otherwise stated) without flashover or puncture.

Dielectric Withstand Voltage Test: The test to determine Dielectric Withstand.

Differentiator Circuit: A circuit that consists of resistors and capacitors designed to change a DC input to an AC output. It is used to make narrow pulse generators and to trigger digital logic circuits. When used in integrated circuits it is known as an inverter.

Digital: (in computer science and engineering) An adjective indicating that something has been developed numerically on a computer or on some other electronic device, based on a binary system, where all numbers are displayed using a series of only zeros and ones.

Digital IC: lntegrated circuits that produce logic voltage signals or pulses that have only two levels of output that are either ON or OFF (yes or no). Some component output examples are: Diagnostic Codes Output, Pulse: Width: Modulated (PWM) Throttle Output, Auxiliary Speed Output, and Fuel Flow Throttle Output.

Digital Multimeter: A digital multimeter or DMM is an electronic measurement tool that can measure voltage, current, resistance, capacitance, temperature, frequency. Learn how to use a digital multimeter.

Diode: An electrical device that will allow current to pass through itself in one direction only. Also see "Zener diode."

Direct Current (DC): A steady flow of electrons moving steadily and continually in the same direction along a conductor from a point of high potential to one of lower potential. It is produced by a battery, generator, or rectifier.

Directional Relay: A protection relay in which the tripping decision is dependent in part upon the direction in which the measured quantity is flowing.

Discharge: To remove electrical energy from a charged body such as a capacitor or battery.

Discharge Current: The surge current that is dissipated through a surge arrester.

Discharge Rate (Battery): The rate of current flow from a cell or battery.

Disconnect Switch: A simple switch that is used to disconnect an electrical circuit. It may or may not have the ability open while the circuit is loaded.

Distribution Automation: A system consisting of line equipment, communications infrastructure, and information technology that is used to gather intelligence about a distribution system. It provides analysis and control in order to optimize operating efficiency and reliability.

Distribution Transformer: A transformer that reduces voltage from the supply lines to a lower voltage needed for direct connection to operate consumer devices.

Distribution Voltage: A nominal operating voltage of up tp 38kV.

Distributor (Ignition): A device which directs the high voltage of the ignition coil to the engine spark plugs.

Distributor Lead Connector: A connection plug in the wires that lead from the sensor in the distributor to the electronic control unit.

Draw-Lead: A cable or solid conductor that has one end connected to the transformer or a reactor winding and the other end drawn through the bushing hollow tube and connected to the top terminal of the bushing.

Drop-Out: A relay drops out when it moves from the energized position to the un-energized position.

Dry-Type Transformers: Transformers that use only dry-type materials for insulation. These have no oils or cooling fluids and rely on the circulation of air about the coils to provide necessary cooling. Such units are usually limited in size to a few hundred kVA.

Dual Voltage Transformer: A transformer that has switched windings allowing its use on two different primary voltages.

Dyer Drive: One type of flywheel engaging mechanism in a starting motor.

E

Earthing Transformer: A three-phase transformer intended essentially to provide a neutral point to a power system for the purpose of grounding.

Earth Fault Protection System: A protection system which is designed to excite during faults to earth.

Eddy Current: The current that is generated in a transformer core due to the induced voltage in each lamination. It is proportional to the square of the lamination thickness and to the square of the frequency.

Effectively Grounded: Intentionally connected conductors or electric equipment to earth, where the connection and conductors are of sufficiently low impedance to allow the conducting of an intended current.

Effective Internal Resistance (Battery): The apparent opposition to current within a battery that manifests itself as a drop in battery voltage proportional to discharge current. Its value is dependent on battery design, state-of-charge, temperature and age.

Electric current: A flow of electric charge — electricity — usually from the movement of negatively charged particles, called electrons.

Electrical Field: The region around a charged body in which the charge has an effect.

Electrical Hazard: A dangerous condition such that contact or equipment failure can result in electric shock, arc flash burn, thermal burn, or blast.

Electrical Relay: A device designed to produce sudden predetermined changes in one or more electrical circuits after the appearance of certain conditions in the controlling circuit.

Electrically Safe Work Condition: A state in which the conductor or circuit part to be worked on or near has been disconnected from energized parts, locked/tagged in accordance with established standards, tested to ensure the absence of voltage, and grounded if determined necessary.

Electricity: The flow of electrons from atom to atom in a conductor.

Electrochemical: The relationship of electricity to chemical changes and with the conversions of chemical and electrical energy. A battery is an electrochemical device.

Electrode: A device that conducts electricity and is used to make contact with non-metal part of an electrical circuit, or that contacts something through which an electrical signal moves. (in electronics) Part of a semiconductor device (such as a transistor) that either releases or collects electrons or holes, or that can control their movement.

Electrolyte (Battery): In a lead-acid battery, the electrolyte is sulfuric acid diluted with water. It is a conductor and also a supplier of hydrogen and sulfate ions for the reaction.

Electron: A negatively charged particle, usually found orbiting the outer regions of an atom; also, the carrier of electricity within solids.

Electro-Hydraulic Valve: A hydraulic valve actuated by a solenoid through variable voltage applied to the solenoid coil.

Electrolyte: Any substance which, in solution, is dissociated into ions and is thus made capable of conducting an electrical current. The sulfuric acid: water solution in a storage battery is an electrolyte.

Electromagnetic: Core of magnetic material, generally soft iron, surrounded by a coil of wire through which electrical current is passed to magnetize the core.

Electromagnetic Clutch: An electromagnetic device which stops the operation of one part of a machine while other parts of the unit keep on operating.

Electromagnetic Field: The magnetic field about a conductor created by the flow of electrical current through it.

Electromagnetic Induction: The process by which voltage is induced in a conductor by varying the magnetic field so that lines of force cut across the conductor.

Electromechanical Relay: An electrical relay in which the designed response is excited by a relative mechanical movement of elements under the action of a current in the input circuit.

Electromotive Force: Potential causing electricity to flow in a closed circuit.

Electron: A tiny particle which rotates around the nucleus of an atom. It has a negative charge of electricity.

Electron Theory: The theory which explains the nature of electricity and the exchange of "free" electrons between atoms of a conductor. It is also used as one theory to explain direction of current flow in a circuit.

Electronics: The control of electrons (electricity) and the study of their behavior and effects. This control is accomplished by devices that resist, carry, select, steer, switch, store, manipulate, and exploit the electron.

Electronic Control Unit (ECU): General term for any electronic controller. See "controller:'

Electronic Governor: The computer program within the engine controller which deterines the commanded fuel delivery based on throttle command, engine speed, and fuel temperature. It replaces the function of a mechanical govnor.

Electronic Ignition System: A system in which the timing of the ignition spark is controlled electronically. Electronic ignition systems have no points or condenser, but instead have a reluctor, sensor, and electronic control unit.

Element: A building block of some larger structure. (in chemistry) Each of more than one hundred substances for which the smallest unit of each is a single atom. Examples include hydrogen, oxygen, carbon, lithium and uranium.

End Point Voltage: Battery Voltage reached at the termination of a discharge. Also Known as the Cut Off Voltage.

Energy: The ability to do work. Energy = Power x Time

Energy Management System: A system designed to ensure safety, security, and reliability to an electrical network. A system in which a dispatcher can monitor and control the flow of electric power by opening and closing switches to route electricity or to isolate a part of the system for maintenance.

Engine Controller: The electronic module which controls fuel delivery, diagnostic outputs, back: up operation, and communications with other electronic modules.

Exciting Current: The magnetizing current of a device such as a transformer. Also known a field current.

Extra High Voltage: An electrical system or cable designed to operate at 345kv (nominal) or higher.

F

Farad: The capacitance value of a capacitor of which there appears a potential difference of one volt when it is charged by a quantity of electricity equal to one coulomb.

Fault Close Rating: The ability, in amps, of a switching device to “close” into a fault of specific magnitude, without excessive arcing.

Fault Current: The current that flows as a result of a short-circuit condition.

Fault Indicator: A device installed on a conductor to determine if current exceeded the indicator’s current rating. Fault indicators sense using use the magnetic field induced by load current.

Feeder: A three phase distribution line circuit used as a source to other three phase and single phase circuits.

Feeder Pillar: A power box, also known as a distribution pillar, is a cabinet used to store electrical equipment. The feeder pillar is a central circuit that distributes electricity from the upstream circuits to the downstream circuits.

Ferro Resonance: A kind of resonance in electric circuits can occur when a circuit is fed from a source with a series of capacitance. The circuit is disrupted by opening a switch. It can cause problems in the electrical power system and pose a risk to the equipment and personnel that use it. In transformers, an over-voltage condition that can occur when the core is excited through capacitance in series with the inductor. This is especially prevalent in transformers that have very low core losses.

Field Current: The magnetizing current of a device such as a transformer. Also known as exciting current.

Field Effect Transistor (FET): A transistor which uses voltage to control the flow of current. Connections are the source (input), drain (output) and gate (control).

Fission: The splitting apart of an atom’s nucleus, releasing heat energy.

Fixed Resistor: A resistor which has only one resistance value.

Flame Resistance: The ability of insulation or jacketing material to resist the support and conveyance of fire.

Flashover: An unintended electrical discharge to ground or another phase. Flashovers can occur between two conductors, across insulators to ground or equipment bushings to ground.

Flash Hazard: A dangerous condition associated with the release of energy caused by an electric arc.

Flash Hazard Analysis: A study investigating a worker’s potential exposure to arc-flash energy, conducted for the purpose of injury prevention, the determination of safe work practices, and the appropriate levels of PPE.

Flash Protection Boundary: An approach limit at a distance from exposed live parts within which a person could receive a second degree burn if an electrical arc flash were to occur.

Flash Suit: A complete FR clothing and equipment system that covers the entire body, except for the hands and feet. This includes pants, jacket, and bee-keeper-type hood fitted with a face shield.

Frequency: In ac systems, the rate at which the current changes direction, expressed in hertz (cycles per second); A measure of the number of complete cycles of a wave-form per unit of time. The number of pulse or wave cycles that are completed in one second. Frequency is measured in Hertz, as in 60Hz (hertz) per second.

Frequency Transducer: A transducer used for the measurement of the frequency of an A.C. electrical quantity.

Fundamental Law of Magnetism: The fundamental law of magnetism is that unlike poles attract each other, and like poles repel each other.

Fuse: A device installed in the conductive path with a predetermined melting point coordinated to load current. Fuses are used to protect equipment from over current conditions and damage. A replaceable safety device for an electrical circuit. A fuse consists of a fine wire or a thin metal strip encased in glass or some fire resistant material. When an overload occurs in the circuit, the wire or metal strip melts, breaking the circuit.

Fused Cutout: A device, normally installed overhead, that is used to fuse a line or electrical apparatus.

Fuse Arcing Time: The amount of time required to extinguish the arc and clear the circuit.

Fuse Link: A replaceable fuse element used in a Fused Cutout.

Fuse Melt Time: The time needed for a fuse element to melt, thereby initiating operation of the fuse. Also known as Melt Time.

G

Gassing (Battery): The evolution of gas from one or more of the electrodes in a cell. Gassing commonly results from local action (self discharge) or from the electrolysis of water in the electrolyte during charging.

Gate: A logic circuit device which makes a YES or NO (one or zero) decision (output) based on two or more inputs.

Gauge: A device to measure the size or volume of something. (v. to gauge) The act of measuring or estimating the size of something.

Generator: A machine which converts mechanical energy into electrical energy.

Generator Step-Up (GSU): Generator step up is done by transformers directly connected to the generator output terminals. This is usually done via busbars in large generating stations. They normally have a high voltage in secondary and high current in primary.

Geothermal Energy: Heat energy that is stored below the earth’s surface.

Grid: A power system's layout of its substations and power lines.

Ground: 1. An electrical term meaning to connect to the earth. 2. A conducting connection, whether intentional or accidental by which an electric circuit, or equipment, is connected to the earth or some conducting body that serves in place of the earth. A ground occurs when any part of a wiring circuit unintentionally touches a metallic part of the machine frame.

Ground Fault: An undesired current path between ground and an electrical potential.

Ground Fault Circuit Interrupter: A GFCI outlet is a device intended for the protection of personnel that functions to de-energize a circuit or portion thereof within an established period of time when a current to ground exceeds some predetermined value that is less than that required to operate the overcurrent protective device of the supply circuit.

Grounded Circuit: A connection of any electrical unit to the frame, engine, or any part of the tractor or machine, completing the electrical circuit to its source.

Grounded Conductor: This an intentional grounded system or circuit conductor.

Grounded (Grounding): There is a connection to the ground or to a body that extends it.

Growler: A device for testing the armature of a generator or motor.

GTO: Gate Turn-off Thyristor

Guy Strain Insulator: An insulator, normally porcelain, used to electrically isolate one part of a down guy from another. Guy Strain Insulators are made by Porcelain Products.

H

Harmonic: A sinusoidal component of the voltage that is a multiple of the fundamental wave frequency.

Harmonic Distortion: The presence of harmonics that change an AC waveform from sinusoidal to complex. They can cause unacceptable disturbance to electronic equipment.

Hazard Risk Category: Categories defined by NFPA 70E-2004 to explain protection levels needed when performing tasks. The values range from 1 to 4. ATPV rated PPE is required for categories 1 through 4 as follows: 1- 4 cal/cm²; 2- 8 cal/cm²; 3- 25 cal/cm²; 4- 40 cal/cm².

Heat Run Test: A test that is used to determine the increase in operating temperature at a given load.

Henry: A unit of measure for inductance. If the rate of change of current in a circuit is one ampere per second and the resulting electromotive force is one volt, then the inductance of the circuit is one henry.

Hertz: 1) A unit of frequency equal to one cycle per second. 2) In alternating current, the changing of the negative and positive poles.

High Intensity Discharge (HID) Lamp: An electric discharge lamp in which the light producing arc is stabilized. Examples of HID lamps include High Pressure Sodium, Metal Halide and Mercury Vapor.

High Pressure Sodium (HPS) Lamp: A High Intensity Discharge light source in which the arc tube’s primary internal element is Sodium Vapor.

High Voltage: An electrical system or cable designed to operate between 46kv and 230kv.

High Voltage System: An electric power system having a maximum roo-mean-square ac voltage above 72.5 kilovolts (kv).

High-speed reclosing: A re-closing scheme where re-closure is carried out without any time delay other than required for deionization.

Hydroelectricity: Electricity generated by flowing water making a turbine spin.

Hydrometer: A float type instrument used to determine the state-of-charge of a battery by measuring the specific gravity of the battery electrolyte (i.e., the amount of sulfuric acid in the electrolyte).

I

Ignition Control Unit: The module that contains the transistors and resistors that controls the electronic ignition.

Impedance: 1) The total opposing force to the flow of current in an ac circuit. 2) The combination of resistance and reactance affecting the flow of an alternating current generally expressed in ohms.

Impulse Test: Tests to confirm that the insulation level is sufficient to withstand over voltages, such as those caused by lightning strikes and switching.

Incident Energy: The amount of energy impressed on a surface, a certain distance from the source, generated during an electrical arc event. Often measured in calories per centimeter squared. (cal/cm²)

Independent Time Measuring Relay: A measuring relay, the specified time for which can be considered as being independent, within specific limits, of the value of the characteristic quantity.

Induced Current: Current in a conductor resulting from a nearby electromagnetic field.

Induced Voltage: A voltage produced in a circuit from a nearby electric field.

Inductance: 1) The property of a circuit in which a change in current induces an electro motive force. 2) Magnetic component of impedance. The property of an electric circuit by which an electromotive force (voltage) is induced in it by a variation of current either in the circuit itself or in a neighboring circuit.

Inductor: A coil of wire wrapped around an iron core.

Inrush Current: The initial surge of current experienced before the load resistance of impedance increases to its normal operating value.

Instantaneous Relay: A relay that operates and resets with no intentional time delay.

Instrument Transformer: A transformer that is only designed to reduce current or voltage from a primary value to a lower value secondary that can be applied to a meter or instrument, at a proportional safer level.

Insulated Gate Field Effect Transistor (IGFET): A special design of transistor that is suitable for handling high voltages and currents. Often used in static power control equipment such as inverters, or controlled rectifiers, due to the flexibility of control of the output.

Insulation: 1) A non-conductive material used on a conductor to separate conducting materials in a circuit. 2) The non-conductive material used in the manufacture of insulated cables.

Insulator: A substance or body that resists the flow of electrical current through it. Also see "Conductor:'

Integrated Circuit (IC): An electronic circuit which utilizes resistors, capacitors, diodes, and transistors to perform various types of operations. The two major types are Analog and Digital Integrated Circuits. Also see "Analog IC" and "Digital IC."

Intermediate Class Arrester: Surge arresters with a high energy handling capability. These are generally voltage classed at 3-120kV.

Internal Impedance (Battery): The opposition to the flow of alternating current at a particular frequency in a cell or battery at a specific state-of-charge and temperature.

Internal Resistance (Battery): The opposition or resistance to the flow of Direct Electric Current within a cell or battery; The sum of the ionic and electronic resistance of the cell components. Its value may vary with the current, state-of-charge, temperature, and age.

Interrupter Switch: A switch equipped with an interrupter for making or breaking connections under load

Inverter: A device with only one input and one output; it inverts or reverses any input.

Ion: An atom having either a shortage or excess of electrons.

Isolation Diode: A diode placed between the battery and the alternator. It blocks any current flow from the battery back through the alternator regulator when the alternator is not operating.

K

Kilowatt (kW): A unit for measuring electrical energy. (demand)

Kilowatt Hour (kWh): One kilowatt of electrical energy produced or used in one hour. (energy)

Kilowatt-hour Meter: A device used to measure electrical energy use.

Knockout Set: A knockout set or also a punch set. An electrician likes to use a knockout punch to make new holes in electrical boxes or panels. You can choose from various sizes of knockouts in a knockout punch set. You can operate manual knockout punches with a wrench.

kVA: 1) Apparent Power expressed in Thousand Volt-Amps. 2) Kilovolt Ampere rating designates the output which a transformer can deliver at rated voltage and frequency without exceeding a specified temperature rise.

KVAR: KVAR is the measure of additional reactive current flow which occurs when the voltage and current flow are not perfectly in phase.

L

Ladder Diagram (LD): One of the IEC 61131-3 programming languages.

Lag: The condition where the current is delayed in time with respect to the voltage in an ac circuit (for example, an inductive load).

Lead: The condition where the current precedes in time with respect to the voltage in an ac circuit (for example, a capacitive load).

Lead Acid Battery: The assembly of one or more cells with an electrolyte based on dilute sulfuric acid and water, a positive electrode of lead dioxide and negative electrodes of lead. Lead Acid batteries all use the same basic chemistry.

Lenz Law: Lenz law is a little bit more on the technical side, but one of the electrical engineers you work with might bring it up (they like to flash their fancy words). Lenz’s law states that the direction of the current induced in a conductor by a changing magnetic field (as per Faraday’s law of electromagnetic induction) is such that the magnetic field created by the induced current opposes the initial changing magnetic field which produced it.

Light Emitting Diode (LED): A solid: state display device that emits infrared light when a forward: biased current flows through it.

Lightning: A flash of light caused by an atmospheric electrical discharge between two clouds, or between a cloud and the earth.

Lightning Arrestor: A device used to protect an electrical component from over-voltage.

Limited Approach Boundary: An approach limit at a distance from an exposed live part within which a shock hazard exists.

Limiting Value of the output current: The upper limit of the output current which cannot, by design be exceeded under any conditions.

Limit Switch: A protective device used to open or close electrical circuits when certain limits, such as temperature or pressure, are reached.

Lines Of Force: Invisible lines which conveniently illustrate the characteristics of a magnetic field and magnetic flux about a magnet.

Line Traps: High voltage lines can be used to transmit R. F. carrier signals for the purposes of voice communication, remote signaling and control. The frequency range from 30 to 500 kHz has proven to be advantageous for high frequency carrier transmission.

Liquid Crystal Display (LCD): A display device utilizing a special crystal fluid to allow segmented displays.

Load: 1) The amount of electrical power required by connected electrical equipment. 2) The total impedance of all the items in the output circuit. An electrical device or devices that use(s) electric power.

Load Break: Refers to a group of rubber insulating products used to electrically connect apparatus with which load can be separated manually.

Load Rejection: When there is a sudden loss of load in the system, the generating equipment is over- Frequency. A load rejection test shows that the system can respond to a sudden loss of load by using its governor. Load banks are used for these tests to make sure electrical power systems are up and running.

Lumen: Standard unit of measure for light flux or light energy. Lamp light output is measured in Lumens.

Lumens Per Watt (LPW): The ratio of light energy output (Lumens) to electrical energy input (Watts).

Luminance: In a direction and at a point of a real or imaginary surface The quotient of the luminous flux at an element of the surface surrounding the point, and propagated in directions defined by an elementary cone containing the given direction.

Lux: The SI unit of luminance. One lux is one lumen per square meter.

M

Magnet: An object surrounded by a magnetic field that has the ability to attract iron or other magnets. Its molecules are aligned.

Magnetic Field: That area near a magnet in which its property of magnetism can be detected. It is shown by magnetic lines of force.

Magnetic Flux: The flow of magnetism about a magnet exhibited by magnetic lines of force in a magnetic field.

Magnetic Induction: The process of introducing magnetism into a bar of iron or other magnetic material.

Magnetic Lines Of Force: Invisible lines which conveniently illustrate the characteristics of a magnetic field and magnetic flux about a magnet.

Magnetic Material: Any material to whose molecules the property of magnetism can be imparted.

Magnetic North: The direction sought by the north pole end of a magnet, such as a magnetic needle, in a horizontal position. It is near the geographic north pole of the Earth.

Magnetic Pickup Assembly: The assembly in a self: integrated electronic ignition system that contains a permanent magnet, a pole piece with internal teeth, and a pickup coil. These parts, when properly aligned, cause the primary circuit to switch off and induce high voltage in the secondary windings.

Magnetic South: The opposite direction from magnetic north towards which the south pole end of a magnet, such as a magnetic needle, is attracted when in a horizontal position. It is near the geographic south pole of the Earth.

Magnetic Switch: A solenoid which performs a simple function, such as closing or opening switch contacts.

Magnetism: The property inherent in the molecules of certain substances, such as iron, to become magnetized, thus making the substance into a magnet

Maximum Permissible Values of the input current and voltage: Values of current and voltage assigned by the manufacturer which the transducer will withstand indefinitely without damage.

MCC: Motor Control Center

Measuring Relay: An electrical relay intended to switch when its characteristics quantity, under specified conditions and with a specified accuracy attains its operating value.

Medium Voltage: An electrical system or cable designed to operate between 1kv and 38kv.

Megawatt: One million watts.

Megohmmeter: A testing device that applies a DC voltage and measures the resistance (in millions of ohms) offered by conductor’s or equipment insulation.

Mercury Vapor Lamp (MV): An HID light source in which the arc tube’s primary internal element is Mercury Vapor.

Metal: Something that conducts electricity well, tends to be shiny (reflective) and is malleable (meaning it can be reshaped with heat and not too much force or pressure).

Metal Clad (Switchgear): An expression used by some manufactures to describe a category of medium voltage switchgear equipment where the circuit breakers are all enclosed in grounded, sheet-steel enclosures.

Metal Enclosed (Switchgear): An expression used by some manufacturers to describe a category of low voltage, 600 volt class switchgear equipment, where the circuit breakers are all enclosed in grounded, sheet-steel enclosures.

Metal Halide Lamp (MH): An HID light source in which the arc tube’s primary internal element is Mercury Vapor in combination with Halides (salts or iodides) of other metals such as Sodium or Scandium.

Meter: An instrument that records the amount of something passing through it, such as electricity.

Microprocessor: An integrated circuit combing logic, amplification and memory functions.

Milliampere: 1/1,OOO,OOO ampere.

Mobile Transformer: A transformer that often is mounted on a leak proof base and can be installed and operated in a semi-trailer, box truck or sea freight container.

Molecule: A unit of matter which is the smallest portion of an element or compound that retains chemical identity with the substance in mass. It is made up of one or more atoms.

Motor: A device that converts electrical energy into mechanical energy.

Multimeter: A testing device that can be set to read ohms (resistance), voltage (force), or amperes (current) of a circuit.

Mutual Induction: Occurs when changing current in one coil induces voltage in a second coil.

MVA: Apparent Power expressed in Million Volt-Amps.

MW: Mega Watt, one million watts.

MWH: Mega Watt Hour, the use of one million watts for one hour.

N

Nameplate Rating: The normal maximum operating rating applied to a piece of electrical equipment. This can include Volts, Amps, horsepower, kW, or any other specific item specification for the equipment.

Natural Magnet: A magnet which occurs in nature, such as a lodestone. Its property of magnetism has been imparted by the magnetic effects of the Earth.

Negative: Designating or pertaining to a kind of electricity. Specifically, an atom that gains negative electrons is negatively charged.

Neutral Conductor: In multiphase circuits, the conductor used to carry unbalanced current. In single-phase systems, the conductor used for a return current path.

Neutral Grounding Resistor: A device that connects the neutral point of a three phase system to ground. Neutral Grounding Resistors are used to limit ground fault current on Neutral Grounded (WYE) systems.

Neutral Ground Reactor: A reactor used to connect the neutral point of a three phase system to ground. Neutral Ground Reactors are used to limit ground fault current on Neutral Grounded (WYE) systems.

Neutron: An uncharged elementary particle. A basic particle in an atom’s nucleus that has a neutral electrical charge. Present in all atomic nuclei except the hydrogen nucleus.

NFPA 70E Standard: Arc Flash standard that provides guidance on implementing appropriate work practices that are required to safeguard workers from injury while working on or near exposed electrical conductors or circuit parts that could become energized.

Nickel Cadmium Battery: The assembly of one or more cells with an alkaline electrolyte, a positive electrode of nickel oxide and negative electrodes of cadmium.

Nominal Voltage: A nominal value assigned to a circuit or system for the purpose of conveniently designating its voltage class.

Nominal Voltage (Battery): Voltage of a fully charged cell or battery when delivering rated capacity at a specific discharge rate. The nominal voltage per cell is 2V for Lead Acid, 1.2V for Nickel-Cadmium, 1.2V for Nickel Metal Hydride and 3.9V for Lithium Ion (small cells only).

Non-Magnetic Material: A material whose molecules cannot be magnetized.

Normally Open and Normally Closed: These terms refer to the position taken by the contacts in a magnetically operated switching device, such as a relay, when the operating magnet is de. energized.

Notching Relay: A relay which switches in response to a specific number of applied impulses.

Nuclear Power: Energy produced by splitting atoms in a nuclear reactor.

Nucleus: The center of an atom that contains both protons and neutrons.

O

Off Peak Power: Power supplied during designated periods of low power system demand.

Off-Load Tap Changer: A tap changer that is not designed for operation while the transformer is supplying load.

Ohm: The standard unit for measuring resistance to flow of an electrical current. Every electrical conductor offers resistance to the flow of current, just as a tube through which water flows offers resistance to the current of water. One ohm is the amount of resistance that limits current flow to one ampere in a circuit with one volt of electrical pressure.

Ohmmeter: An instrument for measuring the resistance in ohms of an electrical circuit.

Ohm's Law: Ohm's Law states that when an electric current is flowing through a conductor, such as a wire, the intensity of the current (in amperes) equals the electromotive force (volts) driving it, divided by the resistance of the conductor. The flow is in proportion to the electromotive force, or voltage, as long as the resistance remains the same.

Oil Breakers: A type of high voltage circuit breaker using mineral oil as both an insulator and an interrupting medium. Typically, these units were produced for use at voltages from 35 kV to as much as 345 kV.

On Load Tap Changer: A tap changer that can be operated while the transformer is supplying load.

Open-Circuit Voltage (Battery): The voltage of a cell or battery when it is not delivering or receiving power.

Open Or Open Circuit: An open or open circuit occurs when a circuit is broken, such as by a broken wire or open switch, interrupting the flow of current through the circuit. It is analogous to a closed valve in a water system.

Operating Current: The current used by a lamp and ballast combination during normal operation.

Operating Current (of a relay): The current at which a relay will pick up.

Operational Amplifier: A high: voltage gain, low: power, linear amplifying circuit device used to add, subtract, average, etc.

OSHA 29 CFR 1910, Subpart S-Electrical: Occupational Safety and Health Standards. Section 1910 Subpart S-Electrical Standard number 1910.333 specifically addresses Standards for Work Practices.

Output Current of a transducer: The current produced by the transducer which is an analog function of the measurand.

Output Load: The total effective resistance of the circuits and apparatus connected externally across the output terminals.

Over Current Relay: A protection relay whose tripping decision is related to the degree by which the measured current exceeds a set value.

Overrunning Clutch: One type of flywheel engaging member in a starting motor.

P

Pad Mounted Transformer: A transformer that is mounted on a pad (usually concrete or polycrete) that is used for underground service. Pad mounted transformers are available in single phase and three phase configurations.

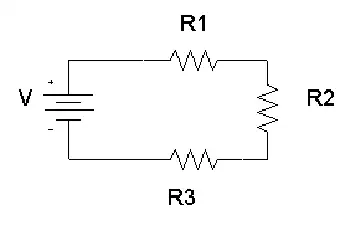

Parallel Circuit: A circuit in which the circuit components are arranged in branches so that there is a separate path to each unit along which electrical current can flow.

Parallel Connection: In the case of DC circuits, a way of joining two or more electrical devices or wires by connecting positive leads and negative leads together.

Particle: A minute amount of something.

Permanent Magnet: A magnet which retains its property of magnetism for an indefinite period.

Phase Angle: The angular displacement between a current and voltage waveform, measured in degrees or radians.

Phase Angle Transducer: A transducer used for the measurement of the phase angle between two a.c. electrical quantities having the same frequency.

Phase Rotation: Phase rotation defines the rotation in a Poly-Phase System and is generally stated as “1-2-3”, counterclockwise rotation. Utilities in the United States use “A-B-C” to define their respective phase names in place “1-2-3”.

Photovoltaic: Refers to the conversion of light into electricity. Photovoltaic

Photovoltaic Cell: The smallest semiconductor element within a photovoltaic module to perform the immediate conversion of light into electrical energy (DC Voltage and DC Current). Photovoltaic Cell

Photovoltaic Efficiency: The ratio of electric power produced by a cell at any instant to the power of the sunlight striking the photovoltaic cell. This is typically 9% to 14% for commercially available cells. Photovoltaic Efficiency

Photovoltaic Module: The smallest environmentally protected, essentially planar assembly of solar cells and ancillary parts, such as interconnections, terminals and protective devices such as diodes intended to generate dc power under unconcentrated sunlight.

Photovoltaic Panel: Often used interchangeably with Photovoltaic Module. Especially in one-module systems , but more accurately used to refer to a physically connected collection of modules (i.e., a laminate string of modules used to achieve a required voltage and current).

Photovoltaic System: A complete set of components for converting sunlight into electricity by the Photovoltaic process, including the array and balance of system devices.

Piezo Electric Device: A device made of crystalline materials, such as quartz, which bend or distort when force or pressure is exerted on them. This pressure forces the electrons to move.

Plastic: Any of a series of materials that are easily deformable; or synthetic materials that have been made from polymers (long strings of some building-block molecule) that tend to be lightweight, inexpensive and resistant to degradation.

Plate: A solid substance from which electrons flow. Batteries have positive plates and negative plates.

PLC: Programmable Logic Controller. A specialized computer for implementing control sequences using software.

Polarity: A collective term applied to the positive (+) and negative (: ) ends of a magnet or electrical mechanism such as a coil or battery.

Pole: One or two points of a magnet at which its magnetic attraction is concentrated.

Pole Shoes: Iron blocks fastened to the inside of a generator or motor housing around which the field or stator coils are wound. The pole shoes may be permanent or electro: magnets.

Positive: Designating or pertaining to a kind of electricity. Specifically, an atom which loses negative electrons and is positively charged.

Potential: The voltage in a circuit. Reference is usually to the AC Voltage.

Potential Transformer: A transformer used to lower the voltage at a set ratio so that the voltage can be measured by instruments and meters at a safe representative level.

Potentiometer: A variable resistor used as a voltage divider.

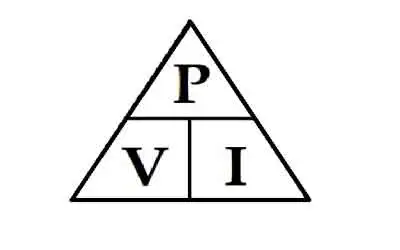

Power: Energy used to do work measured in watts.

Power Factor: The inefficient use of electrical power; the ratio of watts to volt-amperes. The ratio of energy consumed (watts) versus the product of input voltage (volts) times input current (amps). In other words, power factor is the percentage of energy used compared to the energy flowing through the wires.

Power Line Carrier Communication: A means of transmitting information over a power transmission line by using a carrier frequency superimposed on the normal power frequency.

Power Switch Transistor: The part responsible for switching off the primary circuit that causes high voltage induction in the secondary winding in an electronic ignition system.

Power Transformer: A large transformer, generally larger than 1,000 kVA in capacity.

Primary Speed Sensor: An engine speed sensor located inside the actuator housing on the back of the injection pump.

Principle of Turning Force: Explains how magnetic force acts on a current: carrying conductor to create movement of an armature, such as in an electric motor.

Printed Circuit Board: A device used to hold integrated circuit components in place and provide current paths from component to component. Copper pathways are etched into the board with acid.

Prohibited Approach Boundary: An approach limit at a distance from an exposed live part within which work is considered the same as making contact with the live part.

Protection Relay: A relay designed to initiate disconnection of a part of an electrical installation or to a warning signal, in the case of a fault or other abnormal condition in the installation. A protection relay may include more than one electrical element and accessor.

Protection Scheme: The coordinated arrangements for the protection of one or more elements of a power system. A protection scheme may compromise several protection systems.

Protective Device Numbers, ANSI: 2 Time-delay, 21 Distance, 25 Synchronism-check, 27 Undervoltage, 30 Annunciator, 32 Directional power, 37 Undercurrent or underpower, 38 Bearing, 40 Field, 46 Reverse-phase, 47 Phase-sequence voltage, 49 Thermal, 50 Instantaneous.

Proton: A basic particle in an atom’s nucleus that has a positive charge. A particle which, together with the neutron constitutes the nucleus of an atom. It exhibits a positive charge of electricity.

Pulse: A signal that is produced by a sudden ON and OFF of direct current (DC) within a circuit.

Pulse Width Modulated (PWM): A digital electronic signal which consists of a pulse generated at a fixed frequency. The information transmitted by the signal is contained in the width of the pulse. The width of the pulse is changed (modulated) to indicate a corresponding change in the information being transmitted, such as throttle command.

R

Radio: An electrical device that is capable of sending or receiving messages by means of electromagnetic waves through the air.

Rated Capacity (Battery): The number of Amp-Hours a battery can deliver under specific conditions (rate of discharge, end voltage, temperature).

Rated Output: The output at standard calibration.

Reactance: The opposition of inductance and capacitance to alternating current equal to the product of the sine of the angular phase difference between the current and voltage.

Reactive Power: A component of apparent power (volt-amps) which does not produce any real power (watts). It is measured in VARs volt-amps reactive.

Real Power: The average value of the instantaneous product of volts and amps over a fixed period of time in an AC circuit.

Recloser: A switching device that rapidly recloses a power switch after it has been opened by an overload. In reclosing the power feed to the line, the device tests the circuit to determine if the problem is still there. If not, power is not unnecessarily interrupt.

Recombination (Battery): State in which the hydrogen and oxygen gasses normally formed within the battery cell during charging are recombined to form water.

Rectifier: A device (such as a vacuum tube, commutator, or diode) that converts alternating current into direct current.

Regulating Transformer: A transformer used to vary the voltage, or phase angle, of an output circuit. It controls the output within specified limits and compensates for fluctuations of load and input voltage.

Regulator: A device which controls the flow of current or voltage in a circuit to a certain desired level.

Relay: An electrical coil switch that uses a small current to control a much larger current.

Reluctance: The resistance that a magnetic circuit offers to lines of force in a magnetic field.

Reluctor: A metal cylinder, with teeth or legs, mounted on the distributor shaft in an electronic ignition system. The reluctor rotates with the distributor shaft and passes through the electromagnetic field of the sensor.

Residual Current: The algebraic sum, in a multi-phase system, of all the line currents.

Resistance: Something that keeps a physical material (such as a block of wood, electricity, flow of water or air) from moving freely, usually because it provides friction to impede its motion. The opposing or retarding force offered by a circuit or component of a circuit to the passage of electrical current through it. Resistance is measured in ohms.

Resistor: A device usually made of wire or carbon which presents a resistance to current flow.

Restricted Approach Boundary: An approach limit at a distance form an exposed live part within which there is an increased risk of shock, due to electrical arc over combined with inadvertent movement, for personnel working in close proximity to the live part.

Reversible Output Current: An output current which reverses polarity in response to a change of sign or direction of the measurand.

Rheostat: A resistor used for regulating a current by means of variable resistance; rheostats allow only one current path.

Right-Hand Rule: A method used to determine the direction a magnetic field rotates about a conductor, or to find the north pole of a magnetic field in a coil.

Rotor: The rotating part of an electrical machine such as a generator, motor, or alternator.

RTU: Remote Terminal Unit. An IED used specifically for interfacing between a computer and other devices. Sometimes may include control, monitoring, or storage functions.

S

SCADA Systems: Supervisory Control And Data Acquisition. A Computer system used to remotely monitor and control substation equipment.

Scaling Resistor: A resistor added to an output circuit of measurement equipment to provide a scaled voltage output. The output is not a “true” voltage output and may be susceptible to loading errors.

Sealed Cell (Battery): Cells that are free from routine maintenance and can be operated without regard to position.

Self Discharge (Battery): The decrease in the state of charge of a battery or cell, over a period of time, due to internal electro-chemical losses.

Self-Induction: Voltage which occurs in a coil when there is a change of current.

Semiconductor: An element which has four electrons in the outer ring of its atoms. Silicon and germanium are examples. These elements are neither good conductors nor good insulators. Semiconductors are used to make diodes, transistors, and integrated circuits. Semiconductors are important parts of computer chips and certain new electronic technologies, such as light-emitting diodes.

Sendiung Unit: A device, usually located in some part of an engine, to transmit information to a gauge on an instrument panel.

Sensor: A small coil of fine wire in the distributor on electronic ignition systems. The sensor develops an electromagnetic field that is sensitive to the presence of metal. In monitors and controllers, they sense operations of machines and relay the information to a console.

Separator: Any of several substances used to keep one substance from another. In batteries a separator separates the positive plates from the negative plates.

Series Circuit: A circuit in which there is only one path for electricity to flow. All of the current in the circuit must flow through all of the loads.

Series Connection: For DC circuits, a way of joining batteries, electrical devices and wires in such a way that positive leads are connected to negative leads. This is generally done to increase voltage.

Series-Parallel Circuit: A circuit in which some of the circuit components are connected in series and others are connected in parallel.

Service: The conductors and equipment used to deliver energy from the electrical supply system to the system being served.

Service Entrance Cable: The conductors (electrical cable with multiple wires) that connect and carry the electrical current the service conductors (drop or lateral) above ground to the service equipment of the building. It can also be used as a panel feeder and in branch circuits. Service entrance cable are usually of two types: SER or SEU. SER cable is SE (Service Entrance) Style R, which has a reinforcement tape and may be made of copper or aluminum. SEU cable is SE (Service Entrance) Style U, which means it is unarmored. It is typically used as a panel feeder in multi-unit residential settings. Both types should be rated at 600 volts and 90ºC, and is for use in both wet and dry conditions.

Service Life (Battery): The total period of useful life of a battery, normally expressed in the total number of Charge/Discharge cycles.

Shock Hazard: A dangerous electrical condition associated with the possible release of energy caused by contact or approach to energized parts.

Short Circuit: 1. A load that occurs when at ungrounded conductor comes into contact with another conductor or grounded object. 2. An abnorman connection of relatively low impedance, whether made intentionally or by accident, between two points of different potential.

Short (Or Short Circuit): When one part of an electric circuit comes in contact with another part of the same circuit, diverting the flow of current from its desired path. This occurs when one part of a circuit comes in contact with another part of the same circuit, diverting the flow of current from its desired path.

Short Distribution (Lighting): A luminary is classified as having a short light distribution when its max candlepower point falls between 1.0MH 2.25MH TRL. The maximum luminaire spacing-to-mounting height ratio is generally 4.5 or less.

Shunt: A conductor joining two points in a circuit so as to form a parallel circuit through which a portion of the current may pass.

Silicon: A nonmetal, semiconducting element used in making electronic circuits. Pure silicon exists in a shiny, dark-gray crystalline form and as a shapeless powder.

Single-Phase: This implies a power supply or a load that uses only two wires for power. Some “grounded” single phase devices also have a third wire used only for a safety ground, but not connected to the electrical supply or load in any other way except for safety grounding.

Slip Ring: In a generator, motor, or alternator, one of two or more continuous conducting rings from which brushes take, or deliver to, current.

Solar Energy: Energy produced by the sun’s light or heat.

Solenoid: A tubular coil used for producing a magnetic field. A solenoid usually performs some type of mechanical work.

Solid State Circuits: Electronic (integrated) circuits which utilize semiconductor devices such as transistors, diodes and silicon controlled rectifiers.

Solid State Relay: An electronic switching device that switches on or off when a small external voltage is applied across its control terminals. The switching action happens extremely fast.

Spark Plugs: Devices which ignite the fuel by a spark in a spark: ignition engine.

Specific Gravity: The ratio of a weight of any volume of a substance to the weight of an equal volume of some substance taken as a standard, usually water for solids and liquids. When a battery electrolyte is tested the result is the specific gravity of the electrolyte.

Specific-Gravity (Battery): The weight of the electrolyte compared to the weight of an equal volume of pure water. It is used to measure the strength or percentage of sulfuric acid in the electrolyte.

Spike: A short duration of increased voltage lasting only one-half of a cycle.

Split Phase: A split phase electric distribution system is a 3-wire single-phase distribution system, commonly used in North America for single-family residential and light commercial (up to about 100 kVA) applications.

Sprag Clutch Drive: A type of flywheel engaging device for a starting motor.

Stability of a Protection System: The quantity whereby a protection system remains inoperative under all conditions other than those for which it is specifically designed to operate.

Starter Motor: A device that converts electrical energy from the battery into mechanical energy that turns an engine over for starting.

Starting Current: Current required by the ballast during initial arc tube ignition. Current changes as lamp reaches normal operating light level.

Starting Relay: A unit relay which responds to abnormal conditions and initiates the operation of other elements of the protection system.

Static Electricity: An electrical charge built up due to friction between two dissimilar materials.

Static Var Compensator: A device that supplies or consumes reactive power comprised solely of static equipment. It is shunt-connected on transmission lines to provide reactive power compensation.

Stator: The stationary part of an alternator in which another part (the rotor) revolves.

Storage Battery: A group of electrochemical cells connected together to generate electrical energy.

Stranded Conductor: A conductor made by twisting together a group of wire strands.

Stringing Block: A sheave used to support and allow movement of a cable that is being installed. These are normally used overhead but there are also specialized designs used at the entrance to a conduit system.

Substation Configuration Language: Normalized configuration language for substation modeling as expected by IEC 61850-6.

Sub-Transmission System: A high voltage system that takes power from the highest voltage transmission system, reduces it to a lower voltage for more convenient transmission to nearby load centers, delivering power to distribution substations or the largest industrial plants.

Switch: A switch is a device for making, breaking, or changing the connections in an electric current.

Switchgear: A general term covering switching and interrupting devices and their combination with associated control, metering, protective and regulating devices. Also, the assemblies of these devices with associated interconnection, accessories, enclosures and suppplies.

Switching Surges: A high voltage spike that occurs when current flowing in a highly inductive circuit, or a long transmission line, is suddenly interrupted.

Switch, Network: A Switch connects Client systems and servers together to create a network. It selects the path that the data packet will take to its destination by opening and closing an electrical circuit.

System Disturbance Time: The time between fault inception and CB contacts making on successful re-closure.

System Impedance Ratio: The ratio of the power system source impedance to the impedance of the protected zone.

T

Tap Changer: A mechanism usually fitted to the primary winding of a transformer, to alter the turns ratio of the transformer by small discrete amounts over a defined range.

Three-Phase: Multiple phase power supply or load that uses at least three wires where a different voltage phase from a common generator is carried between each pair of wires. The voltage level may be identical but the voltages will vary in phase relationship to each other.

Through Fault Current: The current flowing through a protected zone to a fault beyond that zone.

Time Delay Relay: A relay having an intentional delaying device.

Transducer: A device for converting an electrical signal into a usable direct current or voltage for measurement purposes.

Transducer Error: The actual value of the output minus the intended value of the output expressed algebraically.

Transducer Factor: The product of the current transformer ratio (CTR) and the voltage transformer ratio (VTR). Also called the power ratio.

Transducer with Live Zero: A transducer which gives a predetermined output other than zero when the measurand is zero.

Transducer with Suppressed Zero: A transducer whose output is zero when the measurand is less than a certain value.

Transformer: An electro-magnetic device used to change the voltage in an alternating current electrical circuit.

Transformer Insulation: This is the material that is used to provide electrical insulation between transformer windings at different voltage levels and also between the energized parts and the metal tank of the transformer. Generally, for large transformers used in power applications.

Transformer Ratio: When used in reference to Instrument Transformers, this is simply the ratio of transformation of one or more transformers used in the circuit. If both Cts and VTs are included, the transformer ratio is the product of the CT and the VT.

Transformer Voltage Regulators: Mechanisms that use multiple voltage taps on a transformer-like device to adjust voltage on a power line. As the voltage increases or decreases on the circuit, sensors in the voltage regulator call for the input or output of the regulator.

Transistor: A semiconductor device with three connections, capable of amplification in addition to rectification.

Trickle Charge (Battery): A continuous low rate charge that compensates for the self discharge rate of a battery. Also known as Float Charge.

True Power: Measured in Watts. The power manifested in tangible form such as electromagnetic radiation, acoustic waves, or mechanical phenomena. In a direct current (DC) circuit, or in an alternating current (AC) circuit whose impedance is a pure resistance, the voltage and current are in phase.

True RMS Amps: 1) The effective value of an AC signal. For an amp signal, true RMS is a precise method of stating the amp value regardless of waveform distortion. 2) An AC measurement which is equal in power transfer capability to a corresponding DC current.

True RMS Volts: 1) The effective value of an AC voltage value regardless of the waveform distortion. 2) An AC measurement which is equal power transfer capability to a corresponding DC voltage.

U

Ultra High Voltage (UFV): Transmission systems in the ac voltage exceeds 800,000 volts.

Unbalanced Loads: Refers to an unequal loading of the phases in a three-phase system.

Underground Residential Distribution: (URD) Refers to the system of electric utility equipment that is installed below grade.

Underground Utility Structure: An enclosure for use underground that may be either a handhole or manhole.

Unidirectional Unit: Allows inputs to be measured in one direction only. The stated output range indicates the minimum and maximum input levels.

Unit Electrical Relay: A single relay that can be used alone or in combinations with others.

Unit Protection: A protection system that is designed to operate only for abnormal conditions within a clearly defined zone of the power system.

Universal Bushing Well: This 200 amp rated component is used as part of a system to terminate medium voltage cables to transformers, switchgear and other electrical equipment.

Unrestricted Protection: A protection system which has no clearly defined zone of operation and which achieves selective operation only by time grading.

UPS: Uninterruptable Power Supply

URD: Underground Residential Distribution.

USE: Underground Service Entrance conductor or cable.

V

V: Voltage; Volt.

VAC: Volts AC.

Vacuum Circuit Breakers: Circuit breakers, normally applied at medium voltages, that use vacuum interrupters to extinguish the electrical arc and shut-off flowing current.