What is a Busbar?

By Howard Williams, Assocaite Editor

A busbar is a metallic strip or bar used in electrical systems to conduct electricity within switchgear, distribution panels, and substations. It distributes power efficiently and reduces resistance, enhancing safety and electrical performance.

What is a Busbar?

A busbar is a crucial electrical component used to conduct, distribute, and manage power in electrical systems. Found in commercial, industrial, and utility applications, it helps centralize connections and minimize wiring complexity.

✅ Provides efficient power distribution in electrical panels and substations

✅ Reduces resistance and improves system reliability

✅ Supports compact, organized electrical design for switchgear and distribution boards

A Busbar is an important component of electrical distribution systems, providing a central location for power to be distributed to multiple devices. It is an electrical conductor responsible for collecting electrical power from incoming feeders and distributing it to outgoing feeders. They are made of metal bars or metallic strips and have a large surface area to handle high currents.

How Does it Work?

It is a strip or bar made of copper, aluminum, or another conductive metal used to distribute electrical power in electrical systems. They have a large surface area to handle high currents, which reduces the current density and minimizes losses. They can be insulated or non-insulated, and they can be supported on insulators or wrapped in insulation. They are protected from accidental contact by either a metal earthed enclosure or elevation out of normal reach.

They collect electrical power from incoming feeders and distribute it to outgoing feeders. The bus bar system provides a common electrical junction for various types of electrical equipment, designed to handle high currents with minimal losses. They are often used in industrial applications, where they are installed in electrical panels or switchgear panels.

Different Types of Busbars

Different types of busbars are available on the market, including those made of copper or aluminum, as well as insulated or non-insulated, and segmented or solid busbars. Copper or brass busbars are used in low-voltage applications, while aluminum busbars are used in high-voltage applications. Insulated busbars are used in situations where accidental contact can occur, and segmented busbars are used to connect different types of equipment.

Busbars can also be classified based on their cross-section. A rectangular is the most common type and is often used in low-voltage applications. On the other hand, a tubular busbar is a hollow cylinder used in high-voltage applications. Finally, a circular one has a circular cross-section and is used in high-current applications.

Busbar Types and Characteristics

| Attribute | Copper Busbar | Aluminum Busbar | Laminated Busbar |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conductivity | Excellent (≈100% IACS) | Good (≈61% IACS) | Varies (depends on internal conductor materials) |

| Weight | Heavy | Lightweight | Moderate |

| Cost | Higher | Lower | Higher (due to fabrication complexity) |

| Heat Dissipation | Excellent | Good | Excellent (designed to reduce hot spots) |

| Applications | Switchgear, substations, panels | Bus ducts, high-rise buildings | Compact power modules, UPS, power electronics |

| Mechanical Strength | High | Moderate | Moderate to High |

| Corrosion Resistance | High (especially tinned copper) | Requires anodizing/coating | Depends on encapsulation |

| Ease of Fabrication | Good | Excellent | Complex |

The Purpose of a Busbar in an Electrical System

The primary purpose of an electrical system is to distribute electrical power to different parts of the system. The busbar system collects electrical power from incoming feeders and distributes it to outgoing feeders. Busbars also provide a common electrical junction for different types of electrical equipment.

Busbar and Circuit Breakers

They are often used in conjunction with circuit breakers. Circuit breakers protect electrical circuits from damage caused by overload or short circuits. Additionally, they can be used to isolate the electrical supply in the event of a fault or overload. Circuit breakers are often installed in electrical or switchgear panels, which can be easily accessed and maintained.

Busbars and Electrical Distribution Equipment

They are an essential component of electrical distribution equipment, including electrical panels, switchgear panels, and distribution boards. Electrical panels distribute power to various parts of a building, while switchgear panels control the flow of electrical power in industrial applications. Distribution boards divide the electrical supply into separate circuits at a single location.

Busbar Installation

Installing a busbar involves several basic steps. First, the busbar system's design must be created, considering both the electrical load and the required current-carrying capacity. Then, it is installed in the electrical panel or switchgear panel. Finally, it is connected to the electrical equipment using either bolts, clamps, or welding.

Maintenance

Maintaining a busbar system involves regular inspections and cleaning. The system should be inspected for any damage or corrosion, and the connections should be tightened if they become loose. Regular cleaning of the system is also essential to prevent the buildup of dust or dirt, which can lead to a short circuit.

Safety Precautions

Working with busbars involves high voltage and current, so taking proper safety precautions is essential. The system must be isolated from the electrical system before any maintenance is performed. Personal protective equipment, such as gloves and safety glasses, should be worn while working with busbars. Working on a live system should only be done by trained personnel after ensuring that all necessary safety precautions are in place.

Accidents involving Busbars

Accidents can occur when working with busbars, and they can be dangerous if proper safety precautions are not taken. One common accident that can occur involves accidental contact with a live one. This can cause electrical shock, burns, and even death. Another accident involves short circuits, which can lead to equipment damage, fire, or explosions. These accidents can be prevented by following proper safety procedures and wearing personal protective equipment.

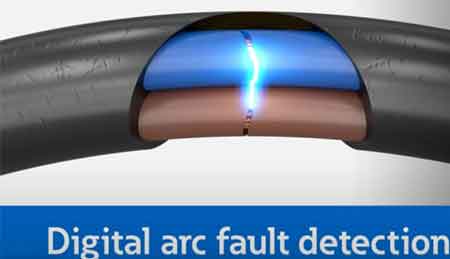

Arc flash accidents, including busbars, are a potential hazard when working with electrical equipment. An arc flash is an electrical explosion that can occur when a fault occurs in an electrical circuit, resulting in a short circuit or electrical discharge. Arc flash accidents can cause severe burns, hearing loss, and even death.

They can be a source of arc flash accidents if proper safety precautions are not taken. For example, if a live busbar comes into contact with an object, it can cause an arc flash. Proper insulation and guarding are necessary to prevent arc flash accidents involving busbars. They should also be installed in a way that minimizes the possibility of accidental contact.

Additionally, they should be designed to handle the expected current load, as overloading can lead to a fault and an arc flash. It is also essential to follow proper maintenance procedures, including regular system inspections and cleaning, to prevent damage or corrosion that can cause faults and arc flashes.

Overall, busbars are related to arc flash accidents as they can be a source of electrical faults that can lead to an arc flash. Therefore, following proper safety procedures, including proper insulation, guarding, and system maintenance, is crucial to prevent arc flash accidents.

Related Articles

When Edison's generator was coupled with Watt's steam engine, large scale electricity generation became a practical proposition. James Watt, the Scottish inventor of the steam condensing engine, was born in 1736. His improvements to steam engines were patented over a period of 15 years, starting in 1769 and his name was given to the electric unit of power, the Watt.

When Edison's generator was coupled with Watt's steam engine, large scale electricity generation became a practical proposition. James Watt, the Scottish inventor of the steam condensing engine, was born in 1736. His improvements to steam engines were patented over a period of 15 years, starting in 1769 and his name was given to the electric unit of power, the Watt.