Electricity Grid - T&D

By R.W. Hurst, Editor

Electricity grid infrastructure delivers power through transmission lines, substations, and smart grid controls, balancing voltage and frequency, integrating renewable energy, enabling demand response, improving reliability, and supporting utilities with real-time monitoring and load management.

What Is the Electricity Grid?

A network of transmission, distribution, and control systems that delivers reliable electrical power to consumers.

✅ Transmits high-voltage power from plants to local networks

✅ Steps down voltage at substations for safe distribution

✅ Integrates renewables with smart grid and demand response

The electricity grid is a complex and essential component of modern society. It provides the power necessary to operate homes, businesses, and industries, and it is constantly evolving to meet the demands of a changing world. From power generation to distribution, transmission lines to load balancing and renewable energy integration, every component is critical in ensuring we can access reliable and affordable energy whenever needed. For a broader primer, resources such as electric power systems outline how these elements interconnect in practice.

At its core, the grid is a system that connects power generation facilities to consumers through transmission lines and distribution systems. It is designed to move electricity from where it is generated to where it is needed, whether in a residential home or a large industrial facility. The term "grid" refers to the interconnectedness of these systems, which allows power to flow from one location to another as needed. The federal energy regulatory commission ferc regulates the grid.

In North America, the transmission and distribution (T&D) grid is managed by federal, state, provincial, and territorial agencies. The grid is divided into various regions, each with its grid operator responsible for ensuring reliable and efficient operation within their respective jurisdiction. For instance, Canada's power delivery network is divided into four main regions: Western Canada, Ontario, Quebec, and the Atlantic region. Similarly, the United States' electricity grid is divided into three major interconnected systems: the Eastern Interconnection, Western Interconnection, and the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT) system. Each region's grid operator works closely with neighbouring grid operators to ensure a seamless flow of electrical power across the interconnected grid, even during periods of high demand or unexpected outages.

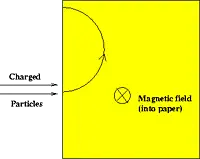

The power delivery network can be broken down into three main components: power generation, transmission, and distribution. Power generation facilities can take many forms, including coal-fired, natural gas, nuclear, and renewable energy sources such as wind and solar. These facilities generate electrical power transmitted over high-voltage transmission lines to substations, where the voltage is lowered for distribution to homes and businesses through a network of distribution lines. For those new to supply technologies, overviews of how electricity is generated cover conventional and renewable pathways.

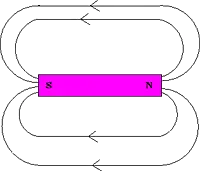

Transmission lines are a critical component of the T&D system, which deliver and produce electricity at higher voltages. T&D provides the means to move large amounts of electrical power over long distances. These lines are typically made of high-strength steel or aluminum and span hundreds of miles. They are also designed to be highly resilient to extreme weather events such as hurricanes, tornadoes, and ice storms. Understanding ratings, capacity, and losses draws on electricity power fundamentals that inform planning and operations.

The distribution system is the final component of the power grid, responsible for delivering electrical power directly to homes and businesses. This system includes transformers, power lines, and meters, which work together to regulate power flow to individual consumers. The distribution system also includes local power generation facilities, such as rooftop solar panels and small-scale wind turbines, which can supplement the power provided by the grid. To see how fuel mixes influence local grids, summaries of sources of electricity highlight regional differences.

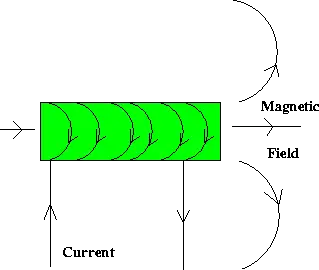

As the world increasingly relies on electrical power, there is a growing need to modernize and upgrade the power delivery network to meet the demands of the 21st century. One approach to this is the development of a smart grid, which uses advanced sensors, communication networks, and analytics to optimize the flow of power and improve reliability. Another approach is the integration of renewable energy sources such as wind and solar into the grid, which can reduce greenhouse gas emissions and improve grid resilience. Advanced planning and forecasting increasingly leverage power system analysis to evaluate contingencies and optimize investments.

Load balancing is another critical function, ensuring that real-time power generation and consumption are matched. This is accomplished through a combination of forecasting, automated control systems, and energy storage facilities such as batteries and pumped hydroelectric storage. In flexible markets, insights into electricity generation help operators schedule resources effectively.

Reliability and resilience are also crucial factors in its overall performance. The grid must be designed to withstand extreme weather events and other disruptions, such as cyberattacks or equipment failures. This requires a combination of robust engineering and effective emergency response planning.

What is an electricity grid, and how does it work?

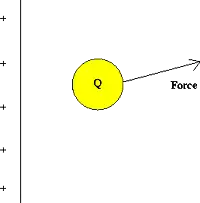

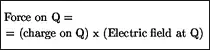

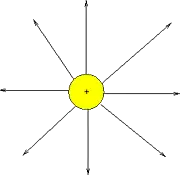

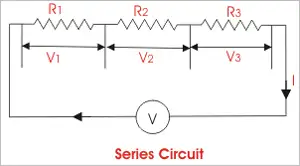

A T&D system is a complex network of power generation facilities, transmission lines, and distribution systems that work together to ensure reliable and affordable energy is available to consumers. At its core, the grid is a system that connects power generation facilities to consumers through transmission lines and distribution systems. It is designed to move electrical power from where it is generated to where it is needed, whether in a residential home or a large industrial facility. The grid uses high-voltage transmission lines to move electrical power over long distances, then lowers the voltage through transformers for distribution to homes and businesses. For foundational clarity, a concise explainer on what electricity is helps connect basic concepts to grid operations.

What is the difference between the transmission and distribution systems?

The transmission system is responsible for moving large amounts of electrical power over long distances at high voltages. This is accomplished through a network of high-voltage transmission lines and substations spanning hundreds of miles. The distribution system delivers electrical power directly to homes and businesses at lower voltages. This system includes transformers, power lines, and meters, which work together to regulate the flow of electricity to individual consumers.

How is renewable energy integrated?

Renewable energy sources such as wind and solar are integrated into the T&D system through a process called interconnection. This involves connecting the renewable energy source to the grid through a substation and transformer, ensuring that the energy generated can be transmitted to consumers. Renewable energy sources can also be connected to the grid through distributed generation, where energy is generated on-site at the point of consumption, such as through rooftop solar panels.

What are the challenges associated with maintaining the reliability and resilience of the T&D system?

Maintaining reliability and resilience is a complex task requiring robust engineering and effective emergency response planning. Some of the challenges associated with this include extreme weather events, cyberattacks, equipment failures, and natural disasters. In addition, as the grid becomes more reliant on renewable energy sources, new challenges may arise related to load balancing and energy storage.

What is a smart grid, and how does it differ from a traditional T&D system?

A smart grid is a modernized version of the traditional T&D system that uses advanced sensors, communication networks, and analytics to optimize the flow of electrical power and improve reliability. Unlike a traditional T&D system, designed to move electrical power from power plants to consumers, a smart grid enables two-way communication between consumers and the grid. This allows for greater control and flexibility in managing energy usage and improved efficiency and reliability.

How can energy storage be used to support the T&D system?

Energy storage can be used to support the T&D system in several ways. One essential function is to provide backup power in the event of a blackout or other disruption to the grid. Energy storage can also help balance the load on the grid, ensuring that power generation and consumption are matched in real-time. In addition, energy storage can help integrate renewable energy sources into the grid by storing excess energy for use during times of low generation.

What is grid modernization, and why is it important for the future of the T&D system?

Grid modernization refers to upgrading and improving the T&D system to meet the demands of a changing world. This may involve the development of a smart grid, the integration of renewable energy sources, and the deployment of advanced sensors and control systems. Grid modernization is important for the future of the T&D system because it will enable greater efficiency, reliability, and sustainability while ensuring that the grid is resilient to emerging threats and challenges.

_1497200293.webp)