What is a Watt-hour?

A watt-hour (Wh) is a unit of energy equal to using one watt of power for one hour. It measures how much electricity is consumed over time and is commonly used to track energy use on utility bills.

Understanding watt-hours is important because it links electrical power (watts) and time (hours) to show the total amount of energy used. To better understand the foundation of electrical energy, see our guide on What is Electricity?

Watt-Hour vs Watt: What's the Difference?

Although they sound similar, watts and watt-hours measure different concepts.

-

Watt (W) measures the rate of energy use — how fast energy is being consumed at a given moment.

-

Watt-hour (Wh) measures the amount of energy used over a period of time.

An easy way to understand this is by comparing it to driving a car:

-

Speed (miles per hour) shows how fast you are travelling.

-

Distance (miles) shows how far you have travelled in total.

Watt-hours represent the total energy consumption over a period, not just the instantaneous rate. You can also explore the relationship between electrical flow and circuits in What is an Electrical Circuit?

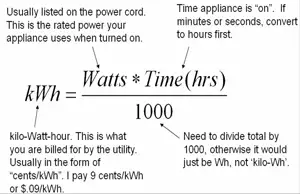

How Watt-Hours Are Calculated

Calculating watt-hours is straightforward. It involves multiplying the power rating of a device by the length of time it operates.

The basic formula is:

Energy (Wh) = Power (W) × Time (h)

This illustrates this relationship, showing how steady power over time yields a predictable amount of energy consumed, measured in watt-hours. For a deeper look at electrical power itself, see What is a Watt? Electricity Explained

Real-World Examples of Watt-Hour Consumption

To better understand how watt-hours work, it is helpful to examine simple examples. Different devices consume varying amounts of energy based on their wattage and the duration of their operation. Even small variations in usage time or power level can significantly affect total energy consumption.

Here are a few everyday examples to illustrate how watt-hours accumulate:

-

A 60-watt lightbulb uses 60 watt-hours (Wh) when it runs for one hour.

-

A 100-watt bulb uses 1 Wh in about 36 seconds.

-

A 6-watt Christmas tree bulb would take 10 minutes to consume 1 Wh.

These examples demonstrate how devices with different power ratings achieve the same energy consumption when allowed to operate for sufficient periods. Measuring energy usage often involves calculating current and resistance, which you can learn more about in What is Electrical Resistance?

Understanding Energy Consumption Over Time

In many cases, devices don’t consume energy at a steady rate. Power use can change over time, rising and falling depending on the device’s function. Figure 2-6 provides two examples of devices that each consume exactly 1 watt-hour of energy but in different ways — one at a steady rate and one with variable consumption.

Here's how the two devices compare:

-

Device A draws a constant 60 watts and uses 1 Wh of energy in exactly 1 minute.

-

Device B starts at 0 watts and increases its power draw linearly up to 100 watts, still consuming exactly 1 Wh of energy in total.

For Device B, the energy consumed is determined by finding the area under the curve in the power vs time graph.

Since the shape is a triangle, the area is calculated as:

Area = ½ × base × height

In this case:

-

Base = 0.02 hours (72 seconds)

-

Height = 100 watts

-

Energy = ½ × 100 × 0.02 = 1 Wh

This highlights an important principle: even when a device's power draw varies, you can still calculate total energy usage accurately by analyzing the total area under its power curve.

It’s also critical to remember that for watt-hours, you must multiply watts by hours. Using minutes or seconds without converting will result in incorrect units.

Fig. 2-6. Two hypothetical devices that consume 1 Wh of energy.

Measuring Household Energy Usage

While it’s easy to calculate energy consumption for a single device, it becomes more complex when considering an entire household's energy profile over a day.

Homes have highly variable power consumption patterns, influenced by activities like cooking, heating, and running appliances at different times.

Figure 2-7 shows an example of a typical home’s power usage throughout a 24-hour period. The curve rises and falls based on when devices are active, and the shape can be quite complex. Saving energy at home starts with understanding how devices consume power; see How to Save Electricity

Instead of manually calculating the area under such an irregular curve to find the total watt-hours used, electric utilities rely on electric meters. These devices continuously record cumulative energy consumption in kilowatt-hours (kWh).

Each month, the utility company reads the meter, subtracts the previous reading, and bills the customer for the total energy consumed.

This system enables accurate tracking of energy use without the need for complex mathematical calculations.

Fig. 2-7. Graph showing the amount of power consumed by a hypothetical household, as a function of the time of day.

Watt-Hours vs Kilowatt-Hours

Both watt-hours and kilowatt-hours measure the same thing — total energy used — but kilowatt-hours are simply a larger unit for convenience. In daily life, we usually deal with thousands of watt-hours, making kilowatt-hours more practical.

Here’s the relationship:

-

1 kilowatt-hour (kWh) = 1,000 watt-hours (Wh)

To see how this applies, consider a common household appliance:

-

A refrigerator operating at 150 watts for 24 hours consumes:

-

150 W × 24 h = 3,600 Wh = 3.6 kWh

-

Understanding the connection between watt-hours and kilowatt-hours is helpful when reviewing your utility bill or managing your overall energy usage.

Watt-hours are essential for understanding total energy consumption. Whether power usage is steady or variable, calculating watt-hours provides a consistent and accurate measure of energy used over time.

Real-world examples — from simple light bulbs to complex household systems — demonstrate that, regardless of the situation, watt-hours provide a clear way to track and manage electricity usage.

By knowing how to measure and interpret watt-hours and kilowatt-hours, you can make more informed decisions about energy consumption, efficiency, and cost savings. For a broader understanding of how energy ties into everyday systems, visit What is Energy? Electricity Explained

Related Articles