Energy is the capacity to do work, powering motion, heat, and electricity. It exists in many forms—kinetic, potential, chemical, thermal, and renewable—transforming constantly to sustain life, industry, and the universe itself.

What is Energy?

Energy is a fundamental concept in physics that describes the capacity of a physical system to perform work. In a sense, energy is the ability to do work.

✅ Exists in forms like kinetic, potential, thermal, chemical, and electrical

✅ Transforms between forms but is conserved under physical laws

✅ Powers human activity, industry, and natural processes

To fully understand what energy is, it helps to start with Basic Electricity, which explains the foundation of how electrical systems operate in daily life.

It can be created or released through chemical reactions, nuclear reactions, and electromagnetic waves. Energy is classified into various types based on its origin, nature, and form, including mechanical, thermal, chemical, electrical, radiant, gravitational, nuclear, and sound. With the rise of technology and the global population, energy use has surged, intensifying the demand for alternative and renewable energy sources such as solar, wind, hydropower, and geothermal.

History and Conceptual Origins

The word "energy" comes from the Greek "energeia," meaning activity or operation. Ancient philosophers, such as Aristotle, used it to describe vitality and action. In the 17th to 19th centuries, scientists such as Newton, Joule, and Helmholtz formalized energy as a measurable quantity in mechanics and thermodynamics. By the 20th century, Einstein’s equation E = mc² had shown that mass itself is a form of energy, reshaping physics and cosmology.

The Law of Conservation of Energy

The law of conservation of energy states that the total amount of energy in a closed system remains constant. Energy cannot be created or destroyed; it can only change form. Whether in chemical reactions, mechanical systems, or nuclear processes, the initial and final total energy always balances.

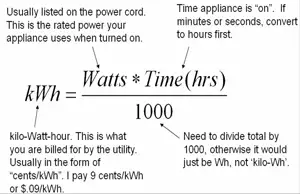

Energy is typically measured in joules (J). One joule equals the work done when a force of one newton moves an object one meter. Larger quantities are measured in kilojoules (kJ) or kilowatt-hours (kWh), which are commonly used in electricity billing.

The Mathematics of Energy

Energy is quantified with precise formulas:

These equations demonstrate how motion, position, and force are translated into measurable energy. The joule is equivalent to newton × meter, tying energy directly to mechanics.

What is Energy Transformation and Efficiency

Energy transformations follow the principles of thermodynamics, where no process is perfectly efficient. For example, in an engine, the conversion of chemical fuel into mechanical work produces useful power, but some energy is always lost as heat. These limitations underscore the importance of studying energy efficiency in both engineering and environmental science.

In real systems, energy constantly transforms:

-

Combustion in engines: chemical → thermal → mechanical → electrical

-

Solar panels: radiant → electrical

-

Hydropower: gravitational potential → kinetic → electrical

Yet no process is perfectly efficient. Friction, resistance, and heat losses dissipate useful energy, echoing the second law of thermodynamics and the concept of entropy. This inefficiency shapes the design of power plants, engines, and renewable systems.

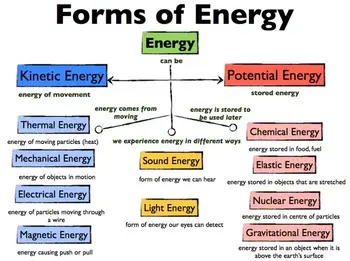

Different Types of Energy?

Energy can be classified into various types based on origin, nature, and form. Each type has unique characteristics, examples, and applications in everyday life and industry.

Mechanical Energy

Mechanical energy is the energy of motion or position. It includes:

-

Potential energy – stored energy due to position or configuration (e.g., water behind a dam).

-

Kinetic energy – energy of motion (e.g., a moving car).

Mechanical energy is widely used in engines, turbines, and machines.

Thermal Energy

Thermal energy is related to the temperature of an object or system, arising from the kinetic motion of its atoms and molecules. It transfers between objects as heat. Everyday examples include boiling water, heating systems, and combustion engines.

Chemical Energy

Chemical energy is stored in the bonds of molecules and released during chemical reactions. Examples include gasoline fueling a car, food fueling our bodies, and batteries powering electronics. It underpins most biological and industrial processes.

Electrical Energy

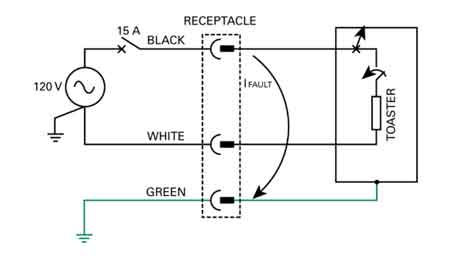

Electrical energy results from the movement of electrons through a conductor. It powers lighting, electronics, appliances, and the global power grid. It is easily transported and converted into other forms of energy. Since energy drives current flow, learning about Electrical Energy and how it relates to Voltage and Current makes the concept more practical.

Radiant Energy

Radiant energy is carried by electromagnetic waves, including visible light, radio waves, and microwaves. It enables vision, communication systems, and solar power technology. Sunlight is the most significant source of radiant energy on Earth.

Gravitational Potential Energy

Gravitational energy is stored by objects in a gravitational field due to their height or mass. Lifting an object, climbing a hill, or operating a hydroelectric dam all rely on gravitational potential energy.

Nuclear Energy

Nuclear energy is released during atomic reactions, such as fission (splitting nuclei) or fusion (combining nuclei). It is harnessed in nuclear power plants to generate electricity and powers stars through fusion.

Sound Energy

Sound energy comes from the vibrations of particles in a medium such as air, water, or solids. It is essential in communication, music, sonar, and countless daily experiences.

Comparison Table of Energy Forms

| Form |

Definition |

Example |

Common Use / Efficiency |

| Mechanical |

Motion or position (kinetic + potential) |

Car in motion, dam reservoir |

Engines, machines, turbines |

| Thermal |

Motion of atoms/molecules, heat transfer |

Boiling water |

Heating, engines |

| Chemical |

Energy in molecular bonds |

Gasoline, food, batteries |

Fuels, metabolism, storage |

| Electrical |

Electron flow through conductors |

Light bulb, power lines |

Appliances, power systems |

| Radiant |

Electromagnetic waves |

Sunlight, radio waves |

Solar panels, communications |

| Gravitational |

Position in a gravitational field |

Falling rock, hydro dam |

Hydropower, lifting systems |

| Nuclear |

Atomic fission/fusion |

Nuclear reactor, stars |

Electricity generation |

| Sound |

Vibrations in the medium |

Music, sonar, speech |

Communication, entertainment |

What is Energy in Everyday Life?

Energy is used in numerous everyday activities, including heating and cooling homes, cooking, transportation, communication, and entertainment. Energy use has increased dramatically with the growth of technology and the global population. However, the availability of energy sources is limited, and the demand is increasing. This has led to a search for alternative and renewable energy sources, such as solar, wind, hydropower, and geothermal energy. The physics of 3 phase electricity and 3 phase power demonstrates how energy is efficiently distributed through modern power grids.

Renewable energy sources, such as solar energy, are gaining popularity due to their clean, sustainable, and renewable nature. Solar energy is derived from the sun's radiation and can be converted into electricity through photovoltaic (PV) cells or concentrated solar power (CSP) systems. Solar energy is utilized for various purposes, including generating electricity, heating water, and drying crops. The relationship between energy, Active Power, and Reactive Power is key to understanding how electricity performs useful work.

What is Energy in Physics?

In physics, the concept of energy is closely tied to thermodynamics, which explains how heat and work are transferred within systems. The law of conservation of energy ensures that energy is never lost, only changed in form through conversion processes. Whether it is the power delivered by an engine, the work performed by a force, or the density of energy stored in fuels and batteries, different forms of energy shape how the physical world operates and how technology supports human progress.

-

Biology: Cells use chemical energy stored in ATP for growth and repair.

-

Physics: Einstein’s equation E = mc² links matter and energy, essential in cosmology and nuclear physics.

-

Engineering: Modern grids rely on energy storage (batteries, pumped hydro), demand response, and smart systems to balance supply and demand.

Energy principles are also explained through fundamental laws, such as Ohm’s Law and Ampere’s Law, which connect voltage, current, and resistance.

Future of Energy

As global demand increases, the future of energy will focus on improving storage systems and raising energy density in fuels and batteries. Advances in renewable systems must also balance the conservation of resources with reliable power delivery. New technologies are being developed to optimize energy conversion and minimize losses, ensuring sustainable solutions for future generations. The future hinges on decarbonization, the integration of renewable energy, and global policy shifts. Fossil fuel limitations and climate change demand innovation in:

-

Large-scale storage (lithium batteries, hydrogen fuel cells).

-

Grid modernization and smart energy management.

-

Sustainable policy frameworks balancing demand with environmental limits.

Energy is not only a scientific concept but also a central issue shaping economies, technology, and our planet’s survival.

How is energy measured and quantified?

Energy is typically measured in joules (J) or kilojoules (kJ). The joule is the unit of measurement for energy in the International System of Units (SI). For example, one joule is the amount of energy needed to move an object with a force of one newton (N) over a distance of one meter (m). Kilojoules (kJ) measure larger amounts of energy, such as the energy content of food or the energy output of power plants.

Energy measurements vary depending on the forms being studied. For instance, thermal systems adhere to the laws of thermodynamics, whereas electrical systems prioritize power output and efficiency. Units like joules, calories, and kilowatt-hours quantify the work done, while energy density helps compare fuels and storage methods in practical applications.

Beyond joules, energy is measured in:

Conversions between units help bridge the gap between physics, engineering, and daily life. For example, a 100-watt light bulb consumes 100 joules every second.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between energy and power?

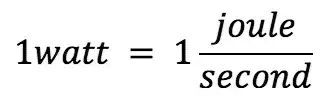

Energy is the capacity to do work; power is the rate of energy transfer, measured in watts (joules per second).

Can energy be created?

No. According to the law of conservation, energy cannot be created or destroyed, only transformed.

What is energy density?

Energy density refers to the amount of energy stored per unit mass or volume, which is particularly important in fuels and batteries.

How is energy related to thermodynamics?

The first law describes conservation; the second law explains inefficiencies and entropy.

Related Articles