Developing states reject Copenhagen plan

By Reuters

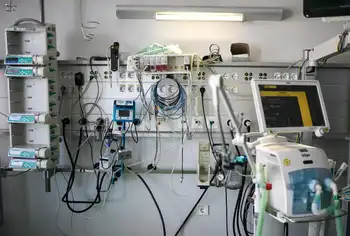

NFPA 70e Training - Arc Flash

Our customized live online or in‑person group training can be delivered to your staff at your location.

- Live Online

- 6 hours Instructor-led

- Group Training Available

China, the world's top emitter, together with India, Brazil and South Africa demand that richer nations do more and have drawn "red lines" limiting what they themselves would accept, the diplomats told Reuters.

The four rejected key targets proposed by the Danish climate talks hosts in a draft text — halving global greenhouse gases by 2050, setting a 2020 deadline for a peak in world emissions, and limiting global warming to a maximum 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial times, European diplomats said.

Developing nations want richer countries to do much more to cut their emissions now before they agree to global emissions targets which they fear may shift the burden of action to them, and crimp their economic growth.

"We cannot agree to the 50/50 (halving emissions by 2050) because it implies that... the remaining (cuts) must be done by developing countries," South Africa's chief climate negotiator Alf Wills said, partly confirming the EU diplomats' comments.

Rich nations' carbon offers so far were far below those recommended by a UN panel of scientists, Wills told Reuters, making clear that developing nations could change their stance if industrialized states tightened their carbon targets.

The dispute underscored a rich-poor rift which has haunted the two-year talks to agree a new global climate deal to succeed the Kyoto Protocol in 2013 and dampens hopes of rescuing the December 7-18 Copenhagen summit.

A legally binding deal is already out of reach for the U.N. talks, with only a political deal possible.

"The paper is defensive. It lays out the red lines for those emerging economies," one European diplomat with knowledge of the paper's contents told Reuters. Hosts Denmark had suggested a cut in world emissions of 50 percent by 2050.

"They say they can't accept two degrees, global peaking in 2020 and 50 percent compared to 1990 levels."

"They don't want any figures under the heading of a shared vision in the Copenhagen draft," a second diplomat said.

Developing nations point out that the developed world is most to blame for greenhouse gases in the atmosphere now, after two centuries of industrialization and burning fossil fuels.

China and the United States, the second-biggest emitter, buoyed hopes that Copenhagen could agree ambitious emissions reduction targets for individual nations, offering proposals for 2020.

India is poised to follow China's example and propose a target to slow growth in its greenhouse gas emissions, but not cap these altogether, government sources told Reuters.

China said it would cut carbon emissions per unit of economic output by up to 45 percent by 2020 versus 2005 levels — by improving energy efficiency and getting more energy from low-carbon, renewable sources.

India says it could cut such carbon intensity by 24 percent by 2020 compared with 2005 levels, according to provisional government estimates obtained by Reuters.

India, the world's fourth highest emitter, is under pressure to announce details of how it will control its growing carbon emissions, and issuing targets will probably strengthen New Delhi's hand at the Copenhagen negotiations.

Government sources said India's Environment Minister Jairam Ramesh will make a statement in parliament in which he could announce the targets.

India's carbon intensity target will let overall emissions rise to 2020, at a slower rate than economic growth, experts say.

"Targets in terms of intensities ought to be very strict, which India's are not," said Asbjorn Aaheim, a researcher at the Center for International Climate and Environmental Research in Oslo.

He said the target would be hard to achieve only if India's economic growth was weak and the population grew above most expectations.

Australia's parliament rejected laws to set up a carbon trading scheme, scuttling a key climate change policy of Prime Minister Kevin Rudd and providing a potential trigger for an early 2010 election.