Electrical Units Explained

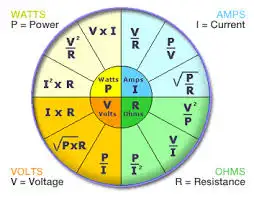

Electrical units measure various aspects of electricity, such as voltage (volts), current (amperes), resistance (ohms), and power (watts). These standard units are crucial in electrical engineering, circuit design, energy monitoring, and ensuring the safe operation of electrical systems.

What are Electrical Units?

Electrical units are standardized measures used to quantify electrical properties in circuits and systems.

✅ Measure voltage, current, resistance, power, and energy

✅ Used in electrical engineering, testing, and design

✅ Support safe and efficient electrical system operations

Electrical units are standardized measurements that describe various aspects of electricity, such as current, voltage, resistance, and power. These units, like amperes for current and volts for voltage, help quantify the behavior and interaction of systems. By understanding electrical units, professionals can assess performance, design circuits, and ensure safety across different applications. These electrical units play a crucial role in the functioning of everything from household appliances to industrial machinery, making them fundamental in engineering and everyday technology.

In common electricity systems, various electrical units of measure, such as magnetic field, are used to describe how electricity flows in the circuit. For example, the unit of resistance is the ohm, while the unit of time is the second. These measurements, often based on SI units, help define the phase angle, which describes the phase difference between current and voltage in AC circuits. Understanding these electrical units is critical for accurately analyzing performance in both residential and industrial applications, ensuring proper function and safety.

Ampere

The ampere is the unit of electric current in the SI, used by both scientists and technologists. Since 1948, the ampere has been defined as the constant current that, if maintained in two straight, parallel conductors of infinite length and negligible circular cross-section, and placed one meter apart in a vacuum, would produce between these conductors a force equal to 2 × 10^7 newtons per meter of length. Named for the 19th-century French physicist André-Marie Ampere, it represents a flow of one coulomb of electricity per second. A flow of one ampere is produced in a resistance of one ohm by a potential difference of one volt. The ampere is the standard unit of electric current, playing a central role in the flow of electricity through electrical circuits.

Coulomb

The coulomb is the unit of electric charge in the metre-kilogram—second-ampere system, the basis of the SI system of physical electrical units. The coulomb is defined as the quantity of electricity transported in one second by a current of one ampere. Named for the I8th—I9th-century French physicist.

Electron Volt

A unit of energy commonly used in atomic and nuclear physics, the electron volt is equal to the energy gained by an electron (a charged particle carrying one unit of electronic charge when the potential at the electron increases by one volt. The electron volt equals 1.602 x IO2 erg. The abbreviation MeV indicates 10 to the 6th (1,000,000) electron volts, and GeV, 10 to the 9th (1,000,000,000). For those managing voltage drop in long circuits, we provide a helpful voltage drop calculator and related formulas to ensure system efficiency.

Faraday

The Faraday (also known as the Faraday constant) is used in the study of electrochemical reactions and represents the amount of electric charge that liberates one gram equivalent of any ion from an electrolytic solution. It was named in honour of the 19th-century English scientist Michael Faraday and equals 6.02214179 × 10^23 coulombs, or 1.60217662 × 10^-19 electrons.

Henry

The henry is a unit of either self-inductance or mutual inductance, abbreviated h (or hy), and named for the American physicist Joseph Henry. One henry is the value of self-inductance in a closed circuit or coil in which one volt is produced by a variation of the inducing current of one ampere per second. One henry is also the value of the mutual inductance of two coils arranged such that an electromotive force of one volt is induced in one if the current in the other is changing at a rate of one ampere per second.

Ohm

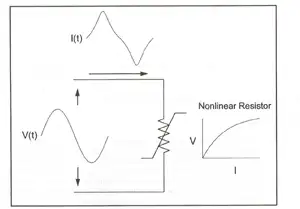

The unit of resistance in the metre-kilogram-second system is the ohm, named in honour of the 19th-century German physicist Georg Simon Ohm. It is equal to the resistance of a circuit in which a potential difference of one volt produces a current of one ampere (1 ohm = 1 V/A); or, the resistance in which one watt of power is dissipated when one ampere flows through it. Ohm's law states that resistance equals the ratio of the potential difference to current, and the ohm, volt, and ampere are the respective fundamental electrical units used universally for expressing quantities. Impedance, the apparent resistance to an alternating current, and reactance, the part of impedance resulting from capacitance or inductance, are circuit characteristics that are measured in ohms. The acoustic ohm and the mechanical ohm are analogous units sometimes used in the study of acoustic and mechanical systems, respectively. Resistance, measured in ohms, determines how much a circuit resists current, as explained in our page on Ohm’s Law.

Siemens

The siemens (S) is the unit of conductance. In the case of direct current (DC), the conductance in siemens is the reciprocal of the resistance in ohms (S = amperes per volt); in the case of alternating current (AC), it is the reciprocal of the impedance in ohms. A former term for the reciprocal of the ohm is the mho (ohm spelled backward). It is disputed whether Siemens was named after the German-born engineer-inventor Sir William Siemens(1823-83) or his brother, the engineer Werner von Siemens (1816-92).

Volt

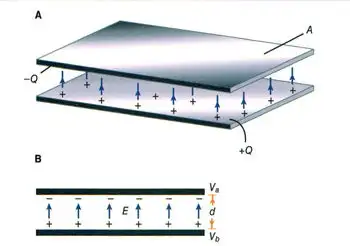

The unit of electrical potential, potential difference, and electromotive force in the metre—kilogram—second system (SI) is the volt; it is equal to the difference in potential between two points in a conductor carrying one ampere of current when the power dissipated between the points is one watt. An equivalent is the potential difference across a resistance of one ohm when one ampere of current flows through it. The volt is named in honour of the I8th—I9th-century Italian physicist Alessandro Volta. Ohm's law defines these electrical units, where resistance equals the ratio of potential to current, and the respective units of ohm, volt, and ampere are used universally for expressing electrical quantities. Energy consumption is measured in kWh, or kilowatt-hours. Explore how devices like ammeters and voltmeters are used to measure current and voltage across components. To better understand how voltage is measured and expressed in volts, see our guide on what is voltage.

Watt

The watt is the unit of power in the SI equal to one joule of work performed per second, or to 1/746 horsepower. An equivalent is the power dissipated in a conductor carrying one ampere of current between points at a one-volt potential difference. It is named in honour of James Watt, British engineer and inventor. One thousand watts equals one kilowatt. Most electrical devices are rated in watts. Learn how a watt defines power in electrical systems and its relationship to volts and amperes through Watts' Law.

Weber

The weber is the unit of magnetic flux in the SI, defined as the amount of flux that, linking a circuit of one turn (one loop of wire), produces in it an electromotive force of one volt as the flux is reduced to zero at a uniform rate in one second. It was named in honour of the 19th-century German physicist Wilhelm Eduard Weber and equals 10 to the 8th maxwells, the unit used in the centimetre—gram—second system.

Related Articles

_1497176752.webp)