Windmills For Electricity Explained

Windmills for electricity use wind energy to generate clean, renewable power. These wind turbines convert kinetic energy into electrical energy, reducing carbon emissions and dependence on fossil fuels.

What are Windmills for Electricity?

Windmills for electricity are modern devices that transform kinetic wind energy into electrical power.

✅ Harness renewable energy for clean power

✅ Reduce carbon footprint and dependence on fossil fuels

✅ Support sustainable power generation worldwide

Windmills for electricity are part of a broader shift toward renewable energy, providing clean alternatives to fossil fuels for homes, businesses, and utilities.

History of Windmills

Windmills for electricity - Mankind has been harnessing the wind's energy for many years. From Holland to traditional farms around the world, windmills were used in the past for pumping water through primitive irrigation systems or to grind grain. Then, the wind turned large "sails" that were connected by a long vertical shaft, which was attached to a grinding machine or a wheel that turned and drew water from a well. Today's turbines harness the energy of the wind to turn large metal blades, which in turn spin a generator that produces electric power. Alongside wind, other renewable energy sources like solar, biomass, and tidal energy are shaping a diversified and sustainable energy future.

From the mid-1970s to the mid-1980s, the United States government collaborated with industry to advance windmill technology for power generation and enable the development of large commercial wind turbines. NASA led this effort at the Lewis Research Center in Cleveland, Ohio, and it was an extraordinarily successful government research and development activity.

National Science Foundation

With funding from the National Science Foundation and later the Department of Energy (DOE), a total of 13 experimental wind turbines were put into operation, including four major wind turbine designs. This research and development program pioneered many of the multi-megawatt turbine technologies in use today, including steel tube towers, variable-speed generators, composite blade materials, partial-span pitch control, as well as aerodynamic, structural, and acoustic engineering design capabilities. The large Windmills For Electricity developed under this effort set several world records for diameter and power output. The Mod-2 wind turbine cluster produced a total of 7.5 megawatts of power in 1981. Government incentives, such as alternative energy tax credits, have played a major role in expanding wind power adoption across North America.

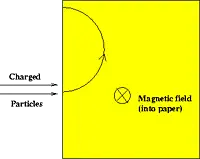

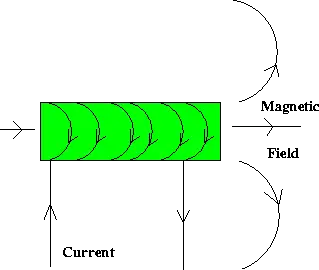

Wind Turbine Technology

In 1987, the Mod-5B was the largest single wind turbine operating in the world with a rotor diameter of nearly 100 meters and a rated power of 3.2 megawatts. It demonstrated an availability of 95 percent, an unparalleled level for a new first-unit wind turbine. The Mod-5B featured the first large-scale variable-speed drive train and a sectioned, two-blade rotor, which enabled easy transport of the blades.

Later, in the 1980s, California provided tax rebates for ecologically harmless wind turbines. These rebates helped fund the first major deployment of wind power for the utility grid. These turbines gathered in large wind parks such as at Altamont Pass, would be considered small and uneconomical by modern wind power development standards.

In the 1990s, as aesthetics and durability became more important, turbines were placed atop steel or reinforced concrete towers. Small generators are connected to the ground tower, and then the tower is raised into position. Larger generators are hoisted into position atop the tower, and a ladder or staircase is located inside the tower to allow technicians to reach and maintain the generator.

Originally, wind turbines were built right next to where their power was needed. With the availability of long-distance electric power transmission, wind generators are now often on wind farms in windy locations, and huge ones are being built offshore, sometimes transmitting power back to land using high-voltage submarine cable. Since wind turbines are a renewable means of generating power, they are being widely deployed, but their cost is often subsidized by taxpayers, either directly or through renewable energy credits. Much depends on the cost of alternative energy sources. The cost of wind generators per unit of power has been decreasing by about 4% per year.

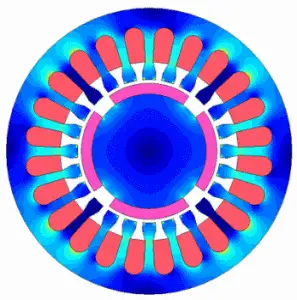

Modern Wind Turbines

The most modern generations of Windmills for electricity are more properly called wind turbines, or wind generators, and are primarily used to generate electric power. Modern windmills are designed to harness the energy of the wind and convert it into electric energy. The largest wind turbines can generate up to 6 MW of power (for comparison, a modern fossil fuel power plant generates between 500 and 1,300 MW). Many large-scale renewable energy projects now combine wind farms with solar and storage systems, ensuring reliable, clean power for communities worldwide.

Small wind turbines can generate as little as a few kilowatts, while larger models produce up to 100 kilowatts or more, depending on design and location. These devices capture moving air, and as wind turbines operate, the kinetic energy generated can be used directly or sent into the electrical grid. On a utility scale, wind farms combine many large turbines to deliver massive amounts of energy, powering thousands of homes and businesses. This range of applications, from residential to industrial, demonstrates the versatility of wind technology in meeting diverse energy needs.

_1497200293.webp)