What is Ohm's Law?

Ohm’s Law defines the essential link between voltage, current, and resistance in electrical circuits. It provides the foundation for circuit design, accurate troubleshooting, and safe operation in both AC and DC systems, making it a core principle of electrical engineering.

What is Ohm’s Law?

Ohm’s Law is a fundamental principle of electrical engineering and physics, describing how voltage, current, and resistance interact in any circuit.

✅ Defines the relationship between voltage, current, and resistance

✅ Provides formulas for design, safety, and troubleshooting

✅ Essential for understanding both AC and DC circuits

When asking what is Ohm’s Law, it is useful to compare it with other fundamental rules like Kirchhoff’s Law and Ampere’s Law, which expand circuit analysis beyond a single equation.

What is Ohm's Law as a Fundamental Principle

Ohm's Law is a fundamental principle in electrical engineering and physics, describing the relationship between voltage, current, and resistance in electrical circuits. Engineers can design safe and efficient electrical circuits by understanding this principle, while technicians can troubleshoot and repair faulty circuits. The applications are numerous, from designing and selecting circuit components to troubleshooting and identifying defective components. Understanding Ohm's Law is essential for anyone working with electrical circuits and systems.

Who was Georg Ohm?

Georg Simon Ohm, born in 1789 in Erlangen, Germany, was a physicist and mathematician who sought to explain the nature of electricity. In 1827, he published The Galvanic Circuit Investigated Mathematically, a groundbreaking work that defined the proportional relationship between voltage, current, and resistance. Though his research was initially dismissed, it later became recognized as one of the cornerstones of modern electrical science.

His work introduced key concepts such as electrical resistance and conductors, and his law became fundamental to circuit design and analysis. The scientific community honored his contribution by naming the unit of resistance — the ohm (Ω) — after him. Today, every student and professional who studies electricity carries his legacy forward.

Georg Simon Ohm

What is Ohm’s Law Formula

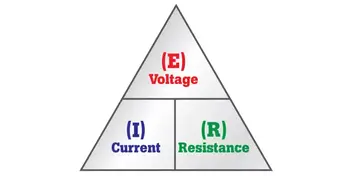

At the heart of the law is a simple but powerful equation:

V = I × R

-

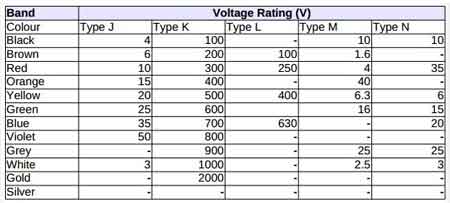

V is voltage, measured in volts (V)

-

I is current, measured in amperes (A)

-

R is resistance, measured in ohms (Ω)

Rearranging the formula gives I = V/R and R = V/I, making it possible to solve for any unknown value when the other two are known. This flexibility allows engineers to calculate required resistor values, predict circuit performance, and confirm safe operating conditions.

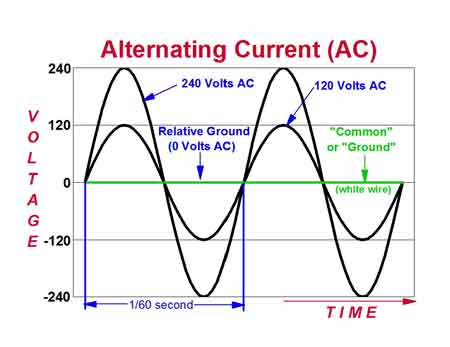

In both DC and AC systems, the law provides the same basic relationship. In AC, where current and voltage vary with time, resistance is replaced with impedance, but the proportional link remains the same.

The Ohm’s Law equation explains how the amount of electric current flowing through a circuit depends on the applied voltage and resistance. Current is directly proportional to voltage and inversely proportional to resistance, illustrating how electrical charge flows under various conditions. To maintain consistency in calculations, the law employs standard units: volts (V) for voltage, amperes (A) for current, and ohms (Ω) for resistance. Since Ohm’s Law formula defines the relationship between these values, it directly connects to related concepts such as electrical resistance and voltage.

Understanding the Formula

The strength of Ohm’s Law lies in its versatility. With just two known values, the third can be calculated, turning raw measurements into useful information. For an engineer, this might mean calculating the resistor needed to protect a sensitive device. For a technician, it may indicate whether a failing motor is caused by excess resistance or a low supply voltage.

How the Formula Works in Practice

Consider a simple example: a 12-volt battery connected to a 6-ohm resistor. Using the law, the current is I = V/R = 12 ÷ 6 = 2 amperes. If resistance doubles, the current halves. If the voltage increases, the current rises proportionally.

In practical terms, Ohm’s Law is used to:

-

calculate resistor values in electronic circuits,

-

verify safe current levels in wiring and equipment,

-

determine whether industrial loads are drawing excessive power,

-

troubleshoot faults by comparing measured and expected values.

Each of these tasks depends on the same simple equation first described nearly two centuries ago. Applying Ohm’s Law often involves calculating current in DC circuits and comparing it with alternating current systems, where impedance replaces simple resistance.

Modern Applications of Ohm’s Law

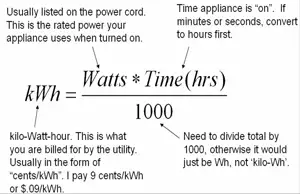

Far from being outdated, Ohm’s Law remains central to modern technology. In electronics, it ensures safe current levels in devices from smartphones to medical equipment. In renewable energy, it governs the design and balance of solar panels and wind turbines. In automotive and electric vehicle systems, battery management and charging depend on accurate application of the law. Even in telecommunications, it ensures signals travel efficiently across cables and transmission lines. In power engineering, Ohm’s Law works alongside Watts Law and power factor to determine efficiency, energy use, and safe operating conditions.

These examples demonstrate that the law is not a relic of early science but an active tool guiding the design and operation of contemporary systems.

Resistance, Conductivity, and Real-World Limits

Resistance is a material’s opposition to current flow, while conductivity — its inverse — describes how freely charge moves. Conductors, such as copper and aluminum, are prized for their high conductivity, while insulators, like rubber and glass, prevent unwanted current flow.

In reality, resistance can change with temperature, pressure, and frequency, making some devices nonlinear. Semiconductors, diodes, and transistors do not always follow Ohm’s Law precisely. In AC systems, resistance expands to impedance, which also considers inductance and capacitance. Despite these complexities, the proportional relationship between voltage and current remains an essential approximation for analysis and design. Exploring basic electricity and related principles of electricity and magnetism shows why Ohm’s Law remains a cornerstone of both theoretical study and practical engineering.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is an example of Ohm's Law?

A simple example in action is a circuit consisting of a battery, a resistor, and a light bulb. If the voltage supplied by the battery increases, the current flowing through the circuit will also increase, causing the light bulb to glow brighter. Conversely, if the resistance of the circuit is increased by adding another resistor, the current flowing through the circuit will decrease, causing the light bulb to dim.

What are the three formulas in Ohm's Law?

The three formulas are I = V/R, V = IR, and R = V/I. These formulas can solve a wide range of problems involving electrical circuits.

Does Ohm’s Law apply to all electrical devices?

Not always. Devices such as diodes and transistors are nonlinear, meaning their resistance changes with operating conditions. In these cases, Ohm’s Law provides only an approximation.

When asking What is Ohm’s Law, it becomes clear that it is far more than a formula. It is the framework that makes electricity predictable and manageable. By linking voltage, current, and resistance, it offers a universal foundation for design, troubleshooting, and innovation. From the earliest experiments to today’s electronics and power grids, Georg Ohm’s insight remains as relevant as ever.