Latest Overhead T&D Articles

Reliability & Protection in Utility Distribution

Reliability and protection in utility distribution are safeguarded through breakers, relays, automation, and fault isolation, ensuring grid stability, preventing outages, and providing safe, resilient power for residential, commercial, and industrial users.

What is Reliability & Protection in Utility Distribution?

Reliability and protection in utility distribution ensure safe, continuous electricity delivery by detecting faults, isolating affected areas, and restoring service efficiently.

✅ Uses relays, reclosers, and breakers to clear faults quickly

✅ Improves outage performance with automation and fault isolation

✅ Adapts to DER integration for stronger grid reliability

Part of enhancing reliability and protection in Utility Distribution involves harmonizing protection strategies with the overall network design, as discussed in our overview of electrical distribution systems.

Utility distribution is where electricity meets the customer, and its reliability depends on strong protection strategies. Faults, equipment failures, and severe weather are inevitable — but with coordinated protection, utilities can minimize outages and restore service quickly. Reliability and protection are not just technical concerns; they define the customer experience and the resilience of the modern grid. One of the key challenges to reliability in utility distribution is dealing with costly interconnection delays, which can slow down system upgrades and impact protection planning.

The Role of Protection in Reliability

In utility networks, reliability is measured through indices such as SAIDI, SAIFI, and CAIDI, which track outage frequency and duration. Behind those numbers lies a simple principle: protection devices must respond fast enough to clear faults but selective enough to avoid cutting off more customers than necessary.

Consider a radial feeder serving a rural community. A single fault along the line can interrupt service for everyone downstream. With the right combination of breakers, reclosers, and fuses, that same fault could be confined to a small segment, keeping most customers supplied while crews make repairs.

Layers of Protection in Utility Distribution

Protection in utility distribution relies on multiple devices working together:

-

Breakers at substations interrupt large fault currents.

-

Reclosers attempt to clear temporary faults and restore service automatically.

-

Sectionalizers detect passing fault current and open to isolate problem areas.

-

Fuses protect lateral branches and small loads.

The effectiveness of these devices comes from careful coordination. Each must operate in the right sequence so that the smallest possible section is taken out of service. Poor coordination risks unnecessary outages, while proper design ensures reliability. Understanding electric power distribution provides the foundation for evaluating how protection devices interact within the broader utility grid.

Comparative Roles of Protection Devices in Utility Distribution

| Device | Typical Fault Response Time | Coverage Area | Reliability Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breaker | Instant to a few cycles | Entire feeder circuit | Prevents catastrophic faults from spreading upstream. |

| Recloser | Less than 1 second, with reclosing attempts | Feeder segments | Clears temporary faults, reducing unnecessary outages. |

| Sectionalizer | Opens after fault current passes | Branch or loop section | Isolates smaller faulted areas, keeping most customers online. |

| Fuse | Seconds (melts under sustained fault) | Small branches, taps | Protects localized loads, acts as final safeguard. |

Effective protection depends on critical components like the electrical insulator, which maintains safety and stability by preventing leakage currents and supporting conductors. To minimize downtime and improve service reliability, utilities often rely on monitoring devices, such as fault indicators, to pinpoint disturbances quickly.

Protection Coordination in Action

Protection is effective only when devices operate in harmony. Two common strategies are:

-

Fuse-saving: a recloser operates first, giving temporary faults a chance to clear before a fuse blows.

-

Fuse-blowing: the fuse operates on sustained faults, preventing upstream devices from unnecessarily tripping.

Modern adaptive relays now adjust thresholds dynamically. For example, when distributed energy is producing heavily, relay settings shift to account for reverse power flow.

Did you know? FLISR (Fault Location, Isolation, and Service Restoration) can reconfigure feeders in under 60 seconds. One Midwestern utility reported a 25% reduction in SAIDI after installing automated reclosers and FLISR software across its suburban service territory.

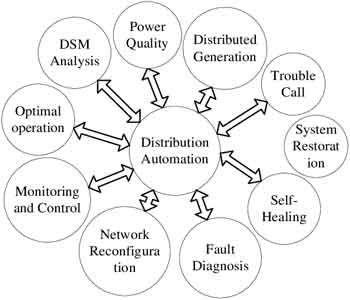

Smart Protection and Automation

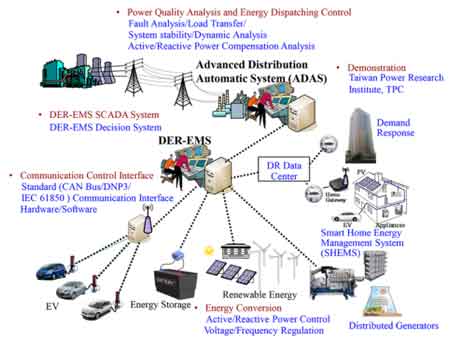

Utilities are increasingly adopting automated protection schemes. Fault Location, Isolation, and Service Restoration (FLISR) technology uses sensors, communications, and smart switches to reroute power in seconds. Instead of dispatching crews to manually isolate a fault, the system reconfigures itself, reducing both outage duration and the number of affected customers.

Automation turns protection from a reactive safeguard into a proactive reliability tool. Utilities that deploy digital relays, SCADA integration, and smart switching see measurable improvements in performance, with lower SAIFI and CAIDI values across their service areas. Advances in distribution automation enable utilities to detect faults, isolate problem areas, and restore service more quickly, directly improving reliability indices such as SAIDI and SAIFI.

Impact of Protection and Automation on Reliability Indices

| Reliability Index | Definition | Effect of Protection & Automation |

|---|---|---|

| SAIDI | Average outage duration per customer (minutes/year) | Automation reduces restoration time by rerouting power quickly. |

| SAIFI | Average number of outages per customer (interruptions/year) | Coordinated reclosers and sectionalizers lower outage frequency. |

| CAIDI | Average outage duration per interruption | Faster fault isolation and service restoration shorten each outage. |

Challenges in a Distributed Era

Distributed energy resources (DERs) such as solar, wind, and storage are transforming how protection operates. Power no longer flows one way from the substation to the customer. Reverse flows can confuse traditional protection settings, while inverter-based resources may not produce fault currents large enough to trigger older devices.

To address this, utilities are deploying directional relays, adaptive settings, and advanced digital relays capable of handling bidirectional power. Protection strategies must evolve in tandem with the grid to maintain reliability as more distributed resources connect at the distribution level. The rapid growth of distributed energy resources has reshaped how utilities design protection schemes, necessitating adaptive relays and more sophisticated coordination strategies.

Barriers to Stronger Protection

Despite technological progress, several barriers remain:

-

Interoperability between legacy and digital equipment is often limited.

-

Communication networks must be robust enough to support widespread automation.

-

Cybersecurity is critical, as protection devices are now part of utility control systems.

-

Workforce skills must expand, with protection engineers learning networking and analytics alongside relay coordination.

Utilities that overcome these barriers position themselves to deliver safer and more reliable services in the decades ahead. Long-term resilience in distribution systems also depends on strong links with electricity transmission, which supplies the bulk power that distribution networks deliver safely to end users.

Reliability and protection in utility distribution are inseparable. Protection devices detect, isolate, and clear faults; reliability is the result of how well those devices are coordinated. With automation, adaptive relays, and smarter strategies, utilities can minimize outages and keep customers connected even as the grid grows more complex. In an era of distributed resources and rising expectations, robust protection is the foundation of reliable utility distribution.

Related Articles

Sign Up for Electricity Forum’s Overhead T&D Newsletter

Stay informed with our FREE Overhead T&D Newsletter — get the latest news, breakthrough technologies, and expert insights, delivered straight to your inbox.

High Voltage AC Transmission Lines

Ac transmission lines deliver alternating current across the power grid using high voltage, overhead conductors, and insulators, controlling reactive power, impedance, and corona effects to minimize losses, improve efficiency, and ensure reliable long-distance electricity transmission.

Understanding the Role of AC Transmission Lines in Power Systems

Three-phase electric power systems are used for high and extra-high voltage AC transmission lines (50kV and above). The pylons must therefore be designed to carry three (or multiples of three) conductors. The towers are usually steel lattices or trusses (wooden structures are used in Germany in exceptional cases) and the insulators are generally glass discs assembled in strings whose length is dependent on the line voltage and environmental conditions. One or two earth conductors (alternative term: ground conductors) for lightning protection are often added to the top of each pylon. For background on material properties, the electrical insulator overview provides relevant design considerations.

Detail of the insulators (the vertical string of discs) and conductor vibration dampers (the weights attached directly to the cables) on a 275,000 volt suspension pylon near Thornbury, South Gloucestershire, England. In some countries, pylons for high and extra-high voltage are usually designed to carry two or more electric circuits. For double circuit lines in Germany, the “Danube” towers or more rarely, the “fir tree” towers, are usually used. If a line is constructed using pylons designed to carry several circuits, it is not necessary to install all the circuits at the time of construction. Medium voltage circuits are often erected on the same pylons as 110 kV lines. Paralleling circuits of 380 kV, 220 kV and 110 kV-lines on the same pylons is common. Sometimes, especially with 110 kV-circuits, a parallel circuit carries traction lines for railway electrification. Additional context on span lengths, conductor bundles, and right of way is covered in this transmission lines reference for practitioners.

High Voltage DC Transmission Pylons

High voltage direct current (HVDC) transmission lines are either monopolar or bipolar systems. With bipolar systems a conductor arrangement with one conductor on each side of the pylon is used. For single-pole HVDC transmission with ground return, pylons with only one conductor cable can be used. In many cases, however, the pylons are designed for later conversion to a two-pole system. In these cases, conductor cables are installed on both sides of the pylon for mechanical reasons. Until the second pole is needed, it is either grounded, or joined in parallel with the pole in use. In the latter case, the line from the converter station to the earthing (grounding) electrode is built as underground cable. Engineers can review converter topologies, pole configurations, and control methods in the direct current technology guide to inform design choices.

Guidance on electrode placement, resistivity, and corrosion protection is summarized in the grounding electrodes overview relevant to HVDC return paths.

Raliway Traction Line Pylons

Pylons used for single-phase AC railway traction lines are similar in construction to pylons used for 110 kV-three phase lines. Steel tube or concrete poles are also often used for these lines. However, railway traction current systems are two-pole AC systems, so traction lines are designed for two conductors (or multiples of two, usually four, eight, or twelve). As a rule, the pylons of railway traction lines carry two electric circuits, so they have four conductors. These are usually arranged on one level, whereby each circuit occupies one half of the crossarm. For four traction circuits the arrangement of the conductors is in two-levels and for six electric circuits the arrangement of the conductors is in three levels. With limited space conditions, it is possible to arrange the conductors of one traction circuit in two levels. Running a traction power line parallel to high-voltage transmission lines for threephase AC on a separate crossarm of the same pylons is possible. If traction lines are led parallel to 380 kV-lines, the insulation must be designed for 220 kV because, in the event of a fault, dangerous overvoltages to the three-phase alternating current line can occur. Traction lines are usually equipped with one earth conductor. In Austria, on some traction circuits, two earth conductors are used. Integration with substation feeders and sectioning posts must align with the power distribution practices used along the route.

Types Of Pylons

Specific Functions:

- anchor pylons (or strainer pylons) utilize horizontal insulators and occur at the endpoints of conductors.

- pine pylon – an electricity pylon for two circuits of three-phase AC current, at which the conductors are arranged in three levels. In pine pylons, the lowest crossbar has a wider span than that in the middle and this one a larger span than that on the top.

- Twisting pylons are anchor pylons at which the conductors are “twisted” so that they exchange sides of the pylon.

- long distance anchor pylon

A long distance anchor pylon is an anchor pylon at the end of a line section with a long span. Large gaps between pylons reduces the restraints on the movement of the attached conductors. In such situations, conductors may be able to swing into contact with each during high wind, potentially creating a short circuit. Long distance anchor pylons must be very stably built due to the large weight of the exceptionally long cables. They are implemented occasionally as portal pylons. In extreme cases, long distance anchor pylons are constructed in pairs, each supporting only a single cable, in an effort to reduce the strain of large spans.

Branch Pylon: In the layout of an overhead electrical transmission system, a branch pylon denotes a pylon which is used to start a line branch. The branch pylon is responsible for holding up both the main-line and the start of the branch line, and must be structured so as to resist forces from both lines. Branch pylons frequently, but not always, have one or more cross beams transverse to the direction of travel of the line for the admission of the branching electric circuits. There are also branch pylons where the cross beams of the branching electric circuits lie in the direction of travel of the main line. Branch pylons without additional cross beams are occasionally constructed. Branch pylons are nearly always anchor pylons (as they normally must ground the forces from the branch line). Branch pylons are often constructed similarly to final pylons; however, at a branch pylon the overhead line resumes in both directions, as opposed to only one direction as with a final pylon.

Anchor Portal: An anchor portal is a support structure for overhead electrical power transmission lines in the form of a portal for the installation of the lines in a switchyard. Anchor portals are almost always steel-tube or steel-framework constructions.

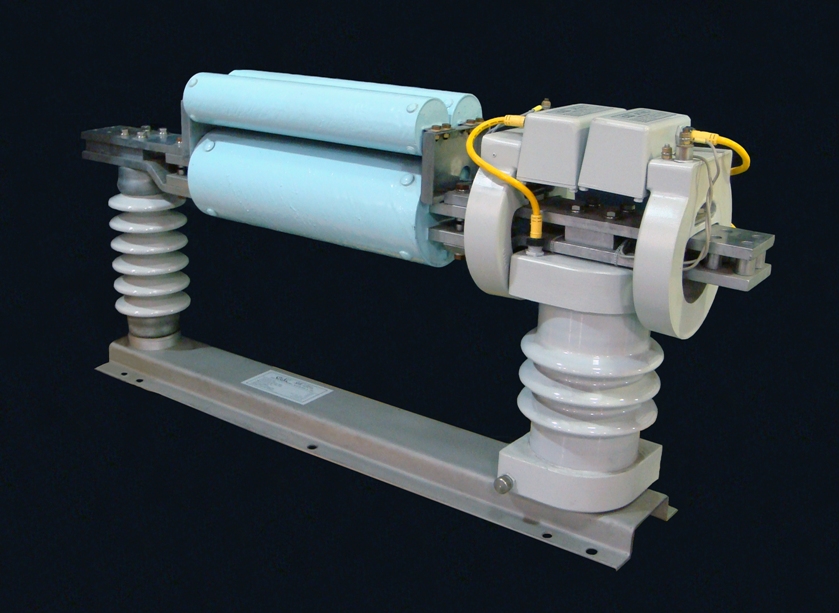

Termination Pylon: Anchor pylons or strainer pylons utilize horizontal insulators and occur at the endpoints of conductors. Such endpoints are necessary when interfacing with other modes of power transmission (see image) and, due to the inflexibility of the conductors, when significantly altering the direction of the pylon chain. Anchor pylons are also employed at branch points as branch pylons and must occur at a maximum interval of 5 km, due to technical limitations on conductor length. Conductors are connected at such pylons by a short conductor cable “strained” between both ends. They often require anchor cables to compensate for the asymmetric attachment of the conductors. Therefore, anchor pylons tend to be more stably built than a support pylon and are often used, particularly in older construction, when the power line must cross a large gap, such as a railway line, river, or valley. A special kind of an anchor pylon is a termination pylon. It is used for the transition of an overhead powerline to an underground cable. A termination pylon at which the powerline runs further as well as overhead line and as underground cable is a branch pylon for a cable branch. For voltages below 30kV, pylon transformers are also used. Twisted pylons are anchor pylons at which the conductors are “twisted” so that they exchange sides of the pylon. Anchor pylons may also have a circuit breaker attached to their crossbeam. These so called switch pylons are operated from the ground by the use of long sticks. The attachment of circuit breakers to pylons is only practical when voltages are less than 50kV. Where sectionalizing or protection is required aloft, utilities are adopting overhead switchgear innovations to reduce footprint and maintenance.

Materials Used

- Wood Pylon

- Concrete Pylon

- Steel Tube Pylon

- Lattice Steel Pylon

Conductor Arrangements

Portal Pylon: In electricity distribution, a portal pylon is a type of pylon with which the cross beams on the conductor cables rest on at least two towers. Portal pylons can be made of wood, concrete, steel tubing or steel lattice. They are used in German railroad wiring because of their enormous space requirement as a rule only for anchor pylons, which have to resist high traction power and as bases for lines in switchgears as anchor portals. Their application and clearances are coordinated with prevailing electrical distribution systems standards for safe operation.

Delta Pylon: A delta pylon is a type of support structure for high-voltage electric power transmission lines. The pylon has a V-shapedtop for the admission of the cross beam. Delta pylons are usually established only for one electric circuit, occasionally for two electric circuits. They are used for voltages up to 765 kV. Delta pylons are far more common in the USA, France, Spain, Italy and formerYugoslavia, while in Germany on delta pylons shifted high voltage transmission lines are very rare.

Single-level Pylon: A single-level pylon is an electricity pylon for an arrangement of all conductor cables on a pylon in one level. The singlelevel pylon leads to a low height of the pylons, connected with the requirement for a large right of way. It is nearly always used for overhead lines for high-voltage direct current transmissions and traction current lines. If three-phase current is used, if the height of pylons may not exceed a certain value.

Two-level Pylon: A two-level pylon is a pylon at which the circuits are arranged in two levels on two crossbars. Two-level pylons are usually designed to carry four conductors on the lowest crossbar and two conductors at the upper crossbar, but there are also other variants, e.g. carrying six conductors in each level or two conductors on the lowest and four on the upper crossbar. Two-level pylons are commonplace in former West-Germany, and are also called Donau pylons after the river Danube.

Three-level Pylon: A three-level pylon is a pylon designed to arrange conductor cables on three crossbars in three levels. For two three-phase circuits (6 conductor cables), it is usual to use fir tree pylons and barrel pylons. Three-level pylons are taller than other pylon types, but require only a small right-of-way. They are very popular in a number of countries.

Three-level Pylon: A three-level pylon is a pylon designed to arrange conductor cables on three crossbars in three levels. For two three-phase circuits (6 conductor cables), it is usual to use fir tree pylons and barrel pylons. Three-level pylons are taller than other pylon types, but require only a small right-of-way. They are very popular in a number of countries.

From: Overhead and Underground T&D Handbook, Volume 1, The Electricity Forum

Related Articles

Single Electricity Market Explained

Single electricity market links regional grids, enabling cross-border trade, renewable integration, and competitive prices. It harmonizes regulations, strengthens energy security, and balances consumption for reliable, efficient, and sustainable electricity supply.

What is a Single Electricity Market?

✅ Enhances grid reliability and cross-border electricity trading

✅ Reduces power outages and stabilizes energy consumption

✅ Supports renewable energy integration and competitive pricing

Understanding the Single Electricity Market: Principles and Impact

The concept of a single electricity market (SEM) has emerged as a transformative approach in the electric power industry. Designed to break down barriers between regional and national electric power markets, a SEM enables interconnected systems to trade electric power more freely. This integration streamlines trading, enhances grid reliability, and ultimately delivers better outcomes for both consumers and the environment.

The governance of the integrated single electricity market (SEM) relies on robust oversight to ensure fairness and transparency. A deputy independent member sits on the SEM Committee, working alongside the utility regulator to oversee policy decisions. Since SEMO is the Single Electricity Market Operator, it manages the wholesale market across jurisdictions, balancing supply and demand while ensuring efficient trading practices. Increasingly, the framework emphasizes the integration of renewable energy sources, which now comprise a significant share of the market, further highlighting the SEM’s role in advancing sustainability and energy security.

The European Union (EU) has pioneered this strategy to combat fragmented energy markets, enabling seamless trading across borders. The success of these markets in regions such as Ireland and Northern Ireland’s All-Island SEM demonstrates the efficiencies that unified regulations and systems can bring. According to SEM annual reports, renewables now contribute more than 40% of electric power supply, up from under 15% in 2007, while emissions intensity has fallen to less than 300 gCO₂/kWh. Consumers have also benefited, with estimated cost savings of hundreds of millions of euros since launch. To understand how soaring energy prices are pushing EU policy toward renewable energy and fossil fuel phase-out, see Europe’s energy crisis is a ‘wake up call’ for Europe to ditch fossil fuels.

How SEMO Works in the Integrated Single Electricity Market

| Function | Description | Impact on Market |

|---|---|---|

| Market Operation | SEMO administers the wholesale electricity market, scheduling and dispatching generation based on bids and demand forecasts. | Ensures electricity is produced and delivered at least cost while maintaining system balance. |

| Settlement & Pricing | Calculates market-clearing prices, settles payments between generators, suppliers, and traders, and publishes transparent pricing data. | Provides fair competition and reliable price signals for investment and trading. |

| Integration of Renewables | Incorporates renewable sources of electricity (e.g., wind, solar) into dispatch schedules, balancing variability with conventional generation and reserves. | Promotes sustainability and supports EU decarbonization targets. |

| Regulatory Compliance | Operates under oversight of the SEM Committee and national utility regulators, ensuring compliance with aligned market rules and codes. | Builds trust in market integrity, fairness, and transparency. |

| Cross-Border Trading | Coordinates with transmission system operators (TSOs) to enable interconnection and market coupling with neighboring regions. | Enhances security of supply, increases efficiency, and lowers overall costs. |

| Dispute Resolution & Transparency | Publishes market reports, handles queries, and participates in regulatory processes with input from independent members (including the deputy independent member). | Strengthens accountability and confidence among stakeholders. |

Key Features of a Single Electricity Market

Market Integration: National or regional electric power systems are coordinated under common trading and regulatory frameworks, eliminating trade barriers and promoting cross-border flows.

Harmonized Regulations: Grid codes, market rules, and technical standards are aligned. This ensures fair competition, non-discriminatory access, and transparency for all market participants. Disputes are settled by joint regulatory authorities, while capacity payments and green certificates (GOs/REGOs) are managed consistently across jurisdictions.

Competitive Pricing: Wholesale prices are determined based on supply and demand, thereby enhancing price signals and encouraging investment in the most suitable technologies.

Security of Supply: By pooling resources and sharing reserves, integrated markets lower the risk of blackouts and price spikes following local disruptions. Balancing markets also enables flexible resources to provide stability in real-time.

To get insight into how EU policy-makers are reacting to surging utility bills, check out this story on how EU balks at soaring electricity prices.

The Irish Single Electricity Market (SEM): A Leading Example

Ireland and Northern Ireland launched one of the earliest and most successful SEMs in 2007, merging their electric power systems into a single market framework. This enabled the dispatch and balancing of electric energy across the entire island, thereby boosting efficiency. The SEM is centrally operated and supported by robust regulatory structures, paving the way for high levels of renewable integration and significant cross-border collaboration.

Recent interconnection projects, such as the upcoming Celtic Interconnector linking Ireland and France, highlight further efforts to deepen integration across Europe. This will enable Ireland to export excess renewable energy, particularly wind, while enhancing France’s access to a flexible supply. Ireland and France will connect their electricity grids - here's how highlights further efforts to deepen market integration across Europe.

Benefits of a Single Electricity Market

-

For Consumers: Enhanced competition helps reduce prices and improve service quality. Fluctuations in individual national markets can be mitigated across the entire region, resulting in more stable pricing.

-

For Producers: Access to a larger market encourages investment in efficient and sustainable energy sources, as well as innovation in electric energy generation and storage.

-

For System Operators: Coordinated scheduling and dispatch lower operational costs, reduce the need for spare capacity, and optimize renewable energy integration.

-

For carbon reduction, shared grids enable nations with abundant renewable energy sources to export clean energy, supporting decarbonization targets across the region.

Challenges and Future Trends

Despite its advantages, creating a single electricity market presents challenges. It requires significant regulatory alignment, market transparency, and ongoing investment in cross-border infrastructure. Market coupling—the seamless linking of day-ahead and intraday mechanisms—is technically complex, requiring robust congestion management and data transparency.

Real-world challenges include Brexit, which introduced new legal and political hurdles for Ireland’s SEM, and subsidy mismatches between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, which have occasionally created policy friction. Grid congestion and the variability of renewable generation also remain persistent issues.

The future of SEMs will likely involve greater digitalization, advanced congestion management, enhanced cross-border interconnections, and new market models that reward flexible, low-carbon resources. The ongoing overhaul in places like Connecticut and Alberta electricity market changes further reinforce the SEM’s global momentum.

Global comparisons highlight the importance of design choices. While Europe’s SEMs are driven by regulatory harmonization, markets like PJM in the United States rely on competitive wholesale structures, and Australia’s National Electricity Market faces unique challenges of distance and network stability. The Nordic model demonstrates how abundant renewable energy sources can be efficiently traded across multiple countries. These comparisons underline the SEM’s adaptability and relevance worldwide.

The single electricity market is a cornerstone of modern power systems reform, delivering lower prices, improved security, and support for renewable energy. While complex to implement, its benefits are substantial—driving market efficiency, reliability, and sustainability for a more integrated, cleaner energy future. For more on global reforms, see Six key trends that shaped Europe's electricity markets.

Related Articles

When it Comes To Digital Marketing, Novice Sailors Can Navigate Calm Waters But Rough Seas Require Expert Sailors...

Digital Marketing Tip: leverage SEO, content marketing, PPC, social media, and analytics to drive qualified traffic, improve engagement, increase conversion rates, and optimize ROI through data-driven testing, segmentation, and continuous optimization.

Digital Marketing Tip Explained

Yes, the current business storm is increasingly difficult to navigate because of the Covid-19 pandemic. So, why is it a bad time to cut your advertising budget?

History has a great way of teaching us lessons. During tough economic times, it might seem logical to make cuts to your advertising budget, but in reality, that’s not a sound idea, as it actually hurts your business. By staying the course, it’s essential to keep your brand and business in the forefront of your customer’s mind, so when this storm has passed (and it will) you will be in a better marketing position that your competitors who chose to hunker down, go into hiding and wait for the storm to pass.

The Lesson: An effective advertising strategy should actually help you increase sales, in good weather AND in bad weather, too!

Effects of Advertising Budget Cuts

From the early 1900s until today, history has shown that effective and thoughtful advertising can help your business increase sales no matter the recession. For example, during the 1923 recession, a study published in the Harvard Business Review (April 1927) showed that “the biggest sales increases were by companies that advertised the most.” To keep that trend going, a study of the 1949, 1954, 1958, and 1961 recessions by Buchen Advertising Inc. showed that “sales and profits dropped for companies who cut back their advertising” and once the recession cleared, the companies who were cutting back actually fell behind their counterparts who had maintained their ad budgets. In the power sector, ongoing interest in smart grid fundamentals keeps buyers researching solutions even during downturns, underscoring why consistent visibility matters.

Study after study has shown similar results, so there’s definitely truth to it. Any money your business may save through budget cuts more than likely will be negligent, due to a decrease in exposure, traffic, leads and more important, SALES! Essential, evergreen topics like power distribution continue to draw qualified traffic that turns into opportunities.

Practice What We Preach: Effective Digital Marketing

Just because you might be on a tight budget, doesn’t mean cutting your digital advertising budget. Like I said, there’s history on your side. Ensure that you have a solid plan in place during both easy AND difficult times.. But especially in difficult times, make sure you are maximizing the effects of your digital advertising investment. Targeting search intent around distributed energy resources can help you capture project stakeholders while they evaluate vendors.

Here’s some tips to consider before your choose to cut your digital advertising budget.

Don’t Waste Money

First and foremost, there is a BIG difference between spending money and wasting money. Don’t waste money. Investing in click-generating campaigns? Great. Are you sure that your investment is getting you “Quality Clicks” that land on the most effective landing pages that are designed an incentivized to produce the right quantity AND quality of leads? Yes, that sounds incredibly simple, but if it was that easy, I wouldn’t mention it. Basically what I’m getting at is not throwing money in areas that don’t focus on your target audience. Here’s a good focus when it comes to REAPing the benefits of digital advertising:

Content that answers practical questions about overhead switchgear innovation often attracts decision makers with near-term purchase intent.

- Reinforce your brand name

- Expose your products and services

- Attract potential customers to your website

- Prospect for new business

Are your existing digital advertising campaigns driven by that philosophy? For instance, highlighting use cases in critical energy storage can reinforce credibility with utility buyers.

Make sure you invest your campaign on the RIGHT target audience, with a campaign that is properly focused on generating a response, with the right calls to action, that lead to a response that you can act on.

The Electricity Forum has a suite of effective digital advertising and content marketing products to suit your budget, that deliver quality exposure, traffic and sales leads.

Utilize Proven Action-Oriented Digital Marketing Campaigns

Have you considered an action campaign? They are a great way to target your audience through a succinct message that generates an action. If you’re having a grand opening, promoting a new product or running an incredible sale, invest in an action campaign that gives your audience all the information they need to act, and present a value proposition and inventive to Act Now! Addressing timely pain points like interconnection delays can intensify urgency and response rates.

Communicate Clearly

Since you’ll be watching your budget extra carefully and dissecting each move you make with surgical precision, it’s imperative to make sure your messaging is clear, concise and appealing to your target market. You’ll also want to make sure that your call to action is solid. Remember, your call to action is a key component to your action campaign. Much like your messaging, your call to action needs to be clear, concise and powerful.

Build Relationships based on

- Budget

- Authority

- Needs

- Timeframe

Building a solid relationship with your customer means listening and focusing your proposal, based on what they tell you about their budget, whether they have the authority to make a purchasing decision, what their most important needs are, and what timeframe they are most likely to act. The greater their “pain”, the shorter their timeframe. Be prepared to act upon this information with a product proposal at the right price, at the right time, to solve their more pressing problem. Educational assets on grounding electrodes can serve as effective lead magnets for engineers and maintenance teams.

Our Electricity Forum representatives are willing to listen to you, assess your digital marketing objectives, and recommend a package of digital advertising and content marketing solutions to suit your budget.

It can be incredibly stressful when times are tough and sales are falling and budgets are shrinking. I get that. But that doesn’t mean you should give up on digital advertising. Like I mentioned earlier, there is proven success in staying the course.

Capitalize On Opportunities

Here’s another thought to ponder. Every crisis brings opportunities. Are you able to adapt your business to changing conditions?

A recession or economic downturn might actually provide an excellent opportunity to launch new products and strengthen your relationship with your customers, based on their changing needs. Sounds weird, right?

In a study titled “Innovating Through Recession,” Andrew Razeghi notes that a recession is the perfect time to “invest in your customers,” saying it’s a time when they need you the most and loyalty hangs in the balance.

“At a time when consumer sentiment is nearly at an all-time low, rather than reduce customer service, use this time to get closer to your customers, connect with them on a deeper level, and show them what’s possible – what the future will hold,” he wrote.

You want your customers to see that you’re still there. If they see that your business is staying positive in tough times, it shouldn’t be surprising that they’d want to stand by you.

The Lesson?...Steady the Helm and Stay the Course

Cutting your digital advertising budget during tough times might seem like the best option when looking at line items on your budget, but don’t let that fool you.

Top digital marketers see opportunities and ways to move forward, ahead of the competition.

Just make sure you don’t make the wrong move. Make sure you chart the right course through rough seas - make the right move.

Staying the course through bad economic times will ensure that you stay upright and increase sales.

Don’t hesitate to contact me to learn more about how The Electricity Forum help craft your strategies.

R.W. (Randy) Hurst

President

The Electricity Forum

randy@electricityforum.com

289-387-1025

Related Articles

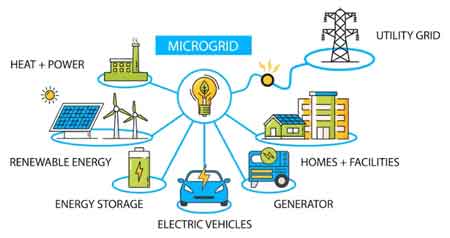

What is a Microgrid?

A microgrid is a localized energy system that can operate independently of or in conjunction with the main grid. By integrating renewable energy, storage, and smart controls, it enhances reliability, supports sustainability, and provides backup power for critical facilities.

What is a Microgrid?

A microgrid is a self-contained power system that generates, distributes, and controls electricity locally. It is essentially a small-scale version of the grid that can function in either grid-connected or islanded mode, ensuring resilience and efficiency.

✅ Integrates renewable energy and battery storage

✅ Provides backup power during outages

✅ Enhances efficiency through smart energy management

Microgrids are gaining popularity as reliable and efficient solutions for modern energy challenges. They are increasingly valuable as the world pursues cleaner energy sources, carbon reduction, and grid modernization. By complementing smart grid infrastructure, they improve system reliability while helping communities and industries adapt to the demands of today’s evolving power networks.

What Defines a Microgrid?

At their core, microgrids are groups of interconnected loads and distributed energy resources (DERs) that are managed as a single, controllable entity. These DERs include renewable generation such as solar, wind, hydro, and geothermal, as well as conventional sources like natural gas or diesel generators. Unlike centralized generation, distributed generation enables local autonomy, reduces transmission and distribution losses, and improves resilience during grid disturbances.

A key advantage is flexibility. Through the point of common coupling (PCC), they can remain tied to the larger grid when beneficial, or disconnect instantly and operate independently when reliability is threatened. This seamless transition strengthens both grid reliability and community energy resilience.

Load Management and Demand Response

Microgrids excel at managing supply and demand in real time. By participating in demand response programs and using smart controllers, they balance intermittent renewable output with load requirements. This reduces strain on central grids, improves power quality, and supports the wider integration of renewable energy. Within broader electrical distribution systems, they also strengthen resiliency by combining renewable generation with storage.

Depending on the application, components may include generation sources, energy storage, and advanced digital control systems. Supervisory control and microgrid controllers monitor and coordinate operations, while effective distribution automation technologies enable them to transition seamlessly between grid-connected and islanded operations. This coordination ensures stability and efficiency under varying conditions.

Energy Storage and the Microgrid

Storage technologies such as batteries, flywheels, and pumped hydro are vital for maintaining energy resilience. They capture excess renewable generation and release it when demand peaks or during outages. Storage also enables black start capability, ensuring a microgrid can restart after a total grid failure. For hospitals, airports, and data centers, this reliability is crucial in preventing disruptions. Critical facilities often depend on robust critical energy storage within microgrids to ensure an uninterrupted power supply.

Traditional vs. Microgrid Operation

Traditional grids rely on centralized power plants transmitting electricity over long distances. By contrast, microgrids operate within defined boundaries, supplying electricity from diverse local sources. This decentralized design reduces transmission losses, increases efficiency, and improves protection against cascading failures.

Smart Grid Technologies and Standards

Microgrids are also becoming increasingly important due to advances in smart grid technologies and grid modernization. They improve monitoring, interconnection, and control. To ensure safe design and operation, industry standards such as IEEE 1547, IEEE 2030.7, and IEC 61850 define interconnection requirements and grid codes. These standards guide the penetration of renewable energy, demand response, and integration with broader electrical networks. Advances in direct current technology are helping DC and hybrid microgrids deliver more efficient local energy systems.

Microgrids can also play a role in improving power quality. A microgrid can help reduce the occurrence of power outages and provide a stable power source to critical loads such as hospitals, data centers, and other essential facilities.

Topologies of a Microgrid

Microgrids can be classified into topologies based on their electrical characteristics. The most common microgrid topologies are AC microgrids, DC microgrids, and hybrid microgrids.

AC Microgrid: An AC microgrid is a type that operates using alternating current (AC). It comprises a combination of renewable energy sources, conventional energy sources, and energy storage systems. AC microgrids are typically designed for larger-scale applications and can be connected to the main grid or operate in island mode.

DC Microgrid: A DC microgrid is a type that operates using direct current (DC). It comprises a combination of renewable energy sources, conventional energy sources, and energy storage systems. DC microgrids are typically designed for smaller-scale applications and can be connected to the main grid or operate in island mode.

Hybrid Microgrid: A hybrid microgrid combines both AC and DC components to form a single system. It comprises a combination of renewable energy sources, conventional energy sources, and energy storage systems. They are typically designed for larger-scale applications and can be connected to the main grid or operate in island mode.

Basic Components of a Microgrid

Microgrids have several components that generate, store, and distribute energy. The basic components in microgrids include:

Power sources can include renewable energy sources, such as solar panels, wind turbines, and hydroelectric generators, as well as conventional power sources, like diesel generators.

Energy storage systems store excess energy generated by power sources, including batteries, flywheels, and pumped hydro storage systems.

Power electronics convert the electrical characteristics of the power generated by power sources and energy storage systems to match the requirements of the loads.

Control systems regulate the flow of energy and maintain stability. They can include controllers, supervisory control, and data acquisition (SCADA) systems.

Microgrid Applications Across Sectors

Microgrids are being deployed in multiple sectors:

-

Community ones for resilience during extreme weather

-

Campus ones at universities to reduce costs and emissions

-

Military base ones for energy security

-

Critical facilities like hospitals, airports, and data centers that require uninterrupted power

Point of common coupling (PCC)

The PCC links the microgrid to the main grid, enabling resource sharing, exporting surplus energy, or islanding in the event of a fault. It ensures safe transitions and reliable operations in all modes.

Economic Considerations and ROI of Microgrids

Microgrid economics are driven by both cost savings and financial benefits. They reduce peak demand charges, allow energy arbitrage, and improve return on investment. Government incentives, tax credits, and supportive policy frameworks make projects more feasible, while long-term savings and sustainability goals strengthen their business case.

Case Studies and Future Outlook

Deployment examples include community microgrids under the New York REV initiative, university campus microgrids in California, and U.S. military base projects aimed at ensuring secure operations. These case studies illustrate the practical benefits of microgrids in real-world applications. As renewable penetration increases, microgrids will remain central to grid modernization, offering economic value, energy resilience, and sustainability.

What is a microgrid? A Microgrid represents a pivotal shift in how electricity is generated, managed, and consumed. By integrating DERs, renewable energy, storage, and advanced controls, they improve reliability, resilience, and carbon reduction outcomes. With supportive policies, strong standards, and growing demand, microgrids will continue to expand as a cornerstone of modern energy infrastructure.

Related Articles

Grounding Electrode

A grounding electrode is a conductive element, such as a metal rod or plate, that connects electrical systems to the earth. It safely disperses fault currents, stabilizes voltage levels, and is essential for electrical safety and code compliance.

What is a Grounding Electrode?

A grounding electrode is a vital component of any electrical system. It is a conductive element, such as a metal rod, plate, or concrete-encased rebar, that connects the electrical system to the earth.

✅ Connects electrical systems to earth to safely discharge fault currents

✅ Helps stabilize voltage and prevent equipment damage

✅ Required for electrical code compliance and personal safety

This connection safely dissipates fault currents, stabilizes voltage levels, and protects both equipment and personnel. Proper grounding is not only essential for electrical safety but is also mandated by national electrical coA grounding electrode is a vital component of any electrical system. It is a conductive element, such as a metal rod, plate, or concrete-encased rebar, that connects the electrical system to the earth. des such as NEC 250.52 and CSA standards. To better understand the broader framework behind safe grounding practices, see our overview of electrical grounding principles.

NEC-Approved Grounding Electrode Types

The National Electrical Code (NEC) outlines various types of grounding electrodes approved for use in electrical installations. These include metal underground water pipes, building steel embedded in concrete, concrete-encased electrodes (commonly referred to as Ufer grounds), ground rings, and rods or pipes driven into the earth. These different electrode types are chosen based on the installation environment and desired longevity.

-

Metal water pipes must be in contact with earth for at least 10 feet.

-

Concrete-encased electrodes use rebar or copper conductor at least 20 feet in length.

-

Ground rods and pipes must be at least 8 feet long and meet diameter standards.

NEC standards such as grounding and bonding requirements are essential for selecting compliant materials and configurations.

Grounding Electrode Conductor (GEC) Sizing and Function

Beyond the electrode itself, the grounding electrode conductor (GEC) plays a critical role in the overall grounding system. The GEC connects the electrode to the main service panel or system grounding point. Sizing of the GEC is determined by the largest ungrounded service-entrance conductor, as outlined in NEC Table 250.66. The conductor must be adequately sized to carry fault current safely without excessive heating or damage.

-

Copper GECs typically range from 8 AWG to 3/0 AWG, depending on the system size.

-

Aluminum conductors may be used but require larger sizes due to lower conductivity.

-

For rod, pipe, or plate electrodes, the maximum required GEC size is 6 AWG copper.

Learn how proper grounding electrode conductor sizing ensures the safe dissipation of fault currents in compliance with NEC 250.66.

Best Practices for Ground Rod Installation

Installation best practices ensure that the electrode system performs as intended. Ground rods must be driven at least 8 feet into the soil, and if multiple rods are required, they must be spaced at least 6 feet apart. Soil conditions, moisture levels, and temperature significantly impact the effectiveness of grounding systems, making proper placement and testing crucial.

-

Electrodes should be installed vertically, where possible, for better conductivity.

-

Ground resistance testing should confirm values below 25 ohms for single rods.

-

Supplemental electrodes may be required to meet code if resistance exceeds this limit.

For deeper insight into how grounding integrates into entire system design, explore our guide on grounding systems and layout strategies.

Soil Resistivity and Its Impact on Grounding System Performance

Soil composition is a critical factor in determining the effectiveness of a grounding electrode. High-resistivity soils such as sand or gravel reduce system reliability. In such cases, chemical ground rods or deeper electrode systems may be required. Soil resistivity testing, using methods like the Wenner or Schlumberger test, can guide engineering decisions.

-

Moist, loamy soil provides the best conductivity.

-

Dry or frozen soil increases resistance significantly.

-

Chemical rods are useful in rocky or high-resistance soils.

If you're working in areas with soil that inhibits conductivity, high-resistance grounding methods may be necessary to maintain performance.

Comparing Types of Ground Rods and Their Applications

There are several types of ground rods available, each with unique properties and applications. Hot-dip galvanized rods are cost-effective and provide reliable performance in many environments. Copper-clad rods, while more expensive, offer enhanced corrosion resistance. Stainless steel and chemical ground rods are typically reserved for specialized applications with extreme soil conditions or longevity requirements.

-

Galvanized rods are economical and meet ASTM A-123 or B-633 standards.

-

Copper-clad rods meet UL 467 and offer superior corrosion protection.

-

Stainless steel and chemical rods are high-cost but high-performance options.

For clarification on the term itself, see our complete definition of electrical grounding and how it applies across systems.

Ensuring Electrical Code Compliance

Code compliance and product specification are essential aspects of grounding design. All rods and connectors must meet standards such as UL 467, ASTM A-123, or CSA. Installers must ensure that products ordered match specifications to avoid liabilities and safety risks. Dissimilar metals should be avoided to prevent galvanic corrosion, which can reduce system lifespan.

-

Ensure product labeling matches listed standards.

-

Avoid mixing copper and galvanized steel in close proximity.

-

Confirm resistance-to-ground targets as part of final inspection.

Grounding System Design for Safety and Reliability

In conclusion, designing and installing an effective grounding electrode system requires a comprehensive understanding of codes, soil science, material properties, and safety considerations. Proper selection and installation of grounding components not only ensure regulatory compliance but also promote system reliability and long-term protection of assets and personnel. Additional techniques and requirements are explained in our article on understanding electrical grounding, which connects grounding electrodes to broader system safety.

Related Articles

Understanding How Overhead Switchgear Innovation Cost-Effectively

How Overhead Switchgear Innovation Cost Effectively? Advanced medium-voltage reclosers, vacuum interrupters, and SCADA-enabled smart sensors enhance reliability, reduce arc-flash risk, cut lifecycle maintenance, and optimize distribution networks for grid modernization and predictive maintenance.

How Overhead Switchgear Innovation Cost Effectively?

BACKGROUND

Achieving many of the globe’s top priorities depends on an unprecedented expansion of electric generation capacity. A report released last year by the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI), for example, forecast that achieving net-zero carbon emissions in the U.S. by mid-century would require a nearly 500 percent increase in electricity generating capacity.

A decarbonized future powered largely by renewable electricity generation depends on a reliable grid, especially the transmission grid. A new report by the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine in the U.S. laid out a blueprint for achieving 2050 net-zero goals, and strengthening and expanding the transmission system was a key component because the transmission system is so important both to integrating renewables and delivering clean energy to where it is consumed. The reliability of the transmission and sub-transmission grid is particularly vital as clean electricity is increasingly relied on to fuel transportation, heating and cooling, and manufacturing and industrial processes. Indeed, the ability to sectionalize and reroute power when an outage hits the sub-transmission system has an outsized impact on reliability because high-voltage grids serve so many homes and businesses. As planners modernize regional networks, an understanding of electricity transmission principles helps explain how long-distance power flows and interconnections support resilience.

The high costs and environmental impacts of status quo solutions

G&W Electric’s Viper®-HV overhead switchgear solution is an important innovation in efforts to simultaneously reduce utility operating expenses (OPEX), improve sub-transmission grid reliability, and integrate more renewables. The genesis of the Viper-HV switching solution was when two utilities approached G&W Electric, one of the U.S.’s largest recloser and switchgear manufacturers, with the request that the company develop a 72.5 kV recloser able to switch and sectionalize sub-transmission power lines to maintain reliability. Deployed on critical transmission lines, such devices expand sectionalizing options without the footprint of new substations.

The reason the utilities and the wider industry were so keen on an overhead solid dielectric solution able to enhance sub-transmission grid reliability was because existing options were inadequate – especially because the sub-transmission system needs both the ability to sectionalize the grid to maintain reliability when faults occur and because it demands advanced monitoring to quickly detect, locate, and respond to outages. Historically, sectionalizing the sub-transmission grid has been handled by motor-operated switches that were insulated either by air or gases such as SF6. Because these products are mechanical devices, they require frequent inspection and maintenance. Not only does this put stress on already tight utility OPEX budgets and a workforce stretched thin by retirements, mechanical devices exposed to the elements can also fail. Utilities increasingly pair such equipment with distribution automation strategies to accelerate fault isolation and service restoration.

Overhead switchgear innovation drives desired and unexpected sub-transmission grid benefits

Development of the Viper-HV overhead switchgear solution took years, with significant input from customers and industry experts. But the advances made deliver important benefits to sub-transmission grid reliability and intelligence, along with improved costs. Indeed, the Viper-HV is a solid dielectric overhead switchgear solution that can respond quickly to temporary faults and deliver the sectionalizing the utilities originally requested, as well as serving as a creative alternative to circuit breakers and bringing reclosing capabilities where applicable. These capabilities align with broader smart grid objectives that emphasize pervasive sensing, coordinated control, and adaptive protection.

Manufactured with a robust, proprietary, time-proven process, the Viper-HV solution is made to solve several pressing sub-transmission grid reliability and cost concerns. For example, it is made to complete a minimum of 10,000 operations without any need for maintenance – which delivers relief to utility OPEX budgets and frees up limited staff for other tasks. Reduced maintenance cycles also streamline power distribution workflows and spare-parts planning for field crews.

Besides providing a low-cost, no-maintenance solution for sub-transmission grid sectionalizing, advanced reclosing technology is important for other reasons as well, including:

Precise location of faults for rapid power restoration

One of the primary challenges facing utilities trying to restore power when there is an outage is finding the fault that caused it. Existing solutions can approximate the location of a fault, which still requires utility personnel to devote precious time to pinpointing its exact location – often in harsh weather conditions – which results in longer restoration times and customer and regulator frustration. The Viper-HV overheard switchgear solution can be equipped with controllers with built-in intelligence enabling precise fault location. The Viper-HV solution includes switching technology plus controllers to include not just impedancebased algorithms but traveling wave fault location determination, which is suitable on longer sub-transmission lines. While most sub-transmission applications are AC, awareness of evolving direct current technology informs protection coordination, converter siting, and interoperability decisions.

Rapid and less costly integration of renewables

Many nations are accelerating deployments of renewable energy to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and achieve ambitious decarbonization targets. Distributed energy resources (DERs) like solar and wind increasingly connect to the transmission and sub-transmission grid – especially when an extra transmission line is added to existing infrastructure to take advantage of an advantageous renewable energy location. DERs introduce complexity to the grid, including more frequent switching than is normal on sub-transmission feeders. The Viper-HV technology, since it was certified as a recloser with 10,000 operations capability, is more suitable than traditional motor operated switches. Furthermore, the form factor of the Viper-HV overhead switchgear is easier to install than other solutions. Pairing sectionalizing schemes with strategically sited critical energy storage can further smooth variability and enhance grid stability during switching events.

Removes need to add expensive and time-consuming grid infrastructure

Another significant benefit of advanced overhead switchgear technology: it can avoid the necessity to add new substations. In cases when a new feeder and circuit breaker need to be added to a sub-transmission system substation, the Viper-HV overhead switchgear solution can increase the speed and lower the cost. That’s because traditional circuit breakers need to be ground-mounted on a concrete pad, which takes up space many substations don’t have and involves permitting that can take a lot of time. By contrast, the Viper-HV overhead switchgear solution can be mounted on the already grounded metal frames most substations have available. This takes no additional space and doesn’t require a time-consuming permitting process.

Advances in technology are essential for increasing the reliability and resiliency of the sub-transmission grid. At the same time, these technologies must lower, rather than elevate, the total overall costs including all aspects of the installation and lifecycle costs (i.e. maintenance, replacement). Sophisticated overhead switchgear technology provides a budget-friendly option for enhancing reliability, resiliency, and helping to green the power grid.