What cities can learn from the biggest battery-powered electric bus fleet in North America

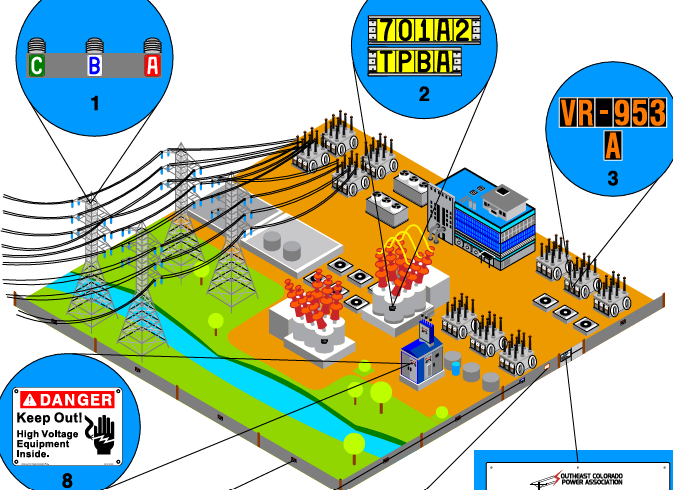

Electrical Testing & Commissioning of Power Systems

Our customized live online or in‑person group training can be delivered to your staff at your location.

- Live Online

- 12 hours Instructor-led

- Group Training Available

Canadian Electric Bus Fleet leads North America as Toronto's TTC deploys 59 battery-electric, zero-emission buses, advancing public transit decarbonization with charging infrastructure, federal funding, lower maintenance, and lifecycle cost savings for a low-carbon urban future.

Key Points

Canada's leading battery-electric transit push, led by Toronto's TTC, scaling zero-emission buses and charging.

✅ Largest battery-electric bus fleet in North America

✅ TTC trials BYD, New Flyer, Proterra for range and reliability

✅ Charging infrastructure, funding, and specs drive 2040 zero-emissions

The largest battery-powered electric bus fleet in North America is Canadian. Toronto's transit system is now running 59 electric buses from three suppliers, and Edmonton's first electric bus is now on the road as well. And Canadian pioneers such as Toronto offer lessons for other transit systems aiming to transition to greener fleets for the low-carbon economy of the future.

Diesel buses are some of the noisier, more polluting vehicles on urban roads. Going electric could have big benefits, even though 18% of Canada's 2019 electricity from fossil fuels remains a factor.

Emissions reductions are the main reason the federal government aims to add 5,000 electric buses to Canada's transit and school fleets by the end of 2024. New funding announced this week as part of the government's fall fiscal update could also give programs to electrify transit systems a boost.

"You are seeing huge movement towards all-electric," said Bem Case, the Toronto Transit Commission's head of vehicle programs. "I think all of the transit agencies are starting to see what we're seeing ... the broader benefits."

While Vancouver has been running electric trolley buses (more than 200, in fact), many cities (including Vancouver) are now switching their diesel buses to battery-electric buses in Metro Vancouver that don't require overhead wires and can run on regular bus routes.

The TTC got approval from its board to buy its first 30 battery-electric buses in November 2017. Its plan is to have a zero-emissions fleet by 2040.

That's a crucial part of Toronto's plan to meet its 2050 greenhouse gas targets, which requires 100 per cent of vehicles to transition to low-carbon energy by then.

But Case said the transition can't happen overnight.

Finding the right bus

For one thing, just finding the right bus isn't easy.

"There's no bus, by any manufacturer, that's been in service for the entire life of a bus, which is 12 years," Case said.

"And so really, until then, we don't have enough experience, nor does anyone else in the industry, have enough experience to commit to an all-electric fleet immediately."

In fact, Case said, there are only three manufacturers that make suitable long-range buses — the kind needed in a city the size of Toronto.

Having never bought electric buses before, the city had no specifications for what it needed in an electric bus, so it decided to try all three suppliers: Winnipeg-based New Flyer; BYD, which is headquartered in Shenzhen, China, but built the TTC buses at its Newmarket, Ont. facility; and California-based Proterra.

They all had their strengths and weaknesses, based on their backgrounds as a traditional non-electric bus manufacturer, a battery maker and a vehicle technology and design startup, respectively.

"Each bus type has its own potential challenges." Case said all three manufacturers are working to resolve any adoption challenges as quickly as possible.

But the biggest challenge of all, Case said, is getting the infrastructure in place.

"There's no playbook, really, for implementing charging infrastructure," he said.

Each bus type needed their own chargers, in some cases using different types of current. Each type has been installed in a different garage in partnership with local utility Toronto Hydro.

Buying and installing them represented about $70 million, or about half the cost of acquiring Toronto's first 60 electric buses. The $140 million project was funded by the federal Public Transit Infrastructure Fund.

Case said it takes about three hours to charge a battery that has been fully depleted. To maximize use of the bus, it's typically put on a long route in the morning, covering 200 to 250 kilometres. Then it's partially charged and put on a shorter run in the late afternoon.

"That way we get as much mileage on the buses as we can."

Cost and reliability?

Besides the infrastructure cost of chargers, each electric bus can cost $200,000 to $500,000 more per bus than an average $750,000 diesel bus.

Case acknowledges that is "significantly" more expensive, but it is offset by fuel savings over time, as electricity costs are cheaper. Because the electric buses have fewer parts than diesel buses, maintenance costs are also about 25 per cent lower and the buses are expected to be more reliable.

As with many new technologies, the cost of electric buses is also falling over time.

Case expects they will eventually get to the point where the total life-cycle cost of an electric and a diesel bus are comparable, and the electric bus may even save money in the long run.

As of this fall, all but one of the 60 new electric buses have been put into service. The last one is expected to hit the road in early December.

Summer testing showed that air conditioning the buses reduced the battery capacity by about 15 per cent.

But the TTC needs to see how much of the battery capacity is consumed by heating in winter, at least when the temperature is above 5 C. Below that, a diesel-powered heater kicks in.

Once testing is complete, the TTC plans to develop specifications for its electric bus fleet and order 300 more in 2023, for delivery between 2023 and 2025.

Potential benefits

Even with some diesel heating, the TTC estimates electric buses reduce fuel usage by 70 to 80 per cent. If its whole fleet were switched to electric buses, it could save $50 million to $70 million in fuel a year and 150 tonnes of greenhouse gases per bus per year, or 340,000 tonnes for the entire fleet.

Other than greenhouse gases, electric buses also generate fewer emissions of other pollutants. They're also quieter, creating a more comfortable urban environment for pedestrians and cyclists.

But the benefits could potentially go far beyond the local city.

"If the public agencies start electrifying their fleet and their service is very demanding, I think they'll demonstrate to the broader transportation industry that it is possible," Case said.

"And that's where you'll get the real gains for the environment."

Alex Milovanoff, a postdoctoral researcher in the University of Toronto's department of civil engineering, did a U of T EV study that suggested electrified transit has a crucial role to play in the low-carbon economy of the future.

His calculations show that 90 per cent of U.S. passenger vehicles — 300 million — would need to be electric by 2050 to reach targets under the global Paris Agreement to fight climate change.

And that would put a huge strain on resources, including both the mining of metals, such as lithium and cobalt, that are used in electric vehicle batteries and the electrical grid itself.

A better solution, he showed, was combining the transition to electric vehicles with a reduction in the number of private vehicles, and higher usage of transit, cycling and walking.

"Then that becomes a feasible picture," he said.

What's needed to make the transition

But in order to make that happen, governments need to make investments and navigate the 2035 EV mandate debate on timelines, he added.

That includes subsidies for buying electric buses and building charging stations so transit agencies don't need to make fares too high. But it also includes more general improvements to the range and reliability of transit infrastructure.

"Electrifying the bus fleet is only efficient if we have a large public transit fleet and if we have many buses on the road and if people take them," Milovanoff said.

In its fall economic update on Monday, the federal government announced $150 million over three years to speed up the installation of zero-emission vehicle infrastructure.

Josipa Petrunic, CEO of the Canadian Urban Transit Research and Innovation Consortium, a non-profit organization focused on zero-carbon mobility and transportation, said that in the past, similar funding has paid for high-powered charging systems for transit systems in B.C. and Ontario. But that's only a small part of what's needed, she said.

"Infrastructure Canada needs to come to the table with the cash for the buses and the whole rest of the system."

She said funding is needed for:

Feasibility studies to figure out how many and what kinds of buses are needed for different routes in different transit systems.

Targets and incentives to motivate transit systems to make the switch.

Incentives to encourage Canadian procurement to build the industry in Canada.

Technology to collect and share data on the performance of electric vehicles so transit systems can make the best-possible decisions to meet the needs of their riders.

Petrunic said that a positive side-effect of electrifying transit systems is that the infrastructure can support, in addition to buses, electric trucks for moving freight.

"It's not a lot given that we have 15,000 buses out there in the transit fleet," she said.

"But we should be able to get a lot further ahead if we match the city commitments to zero emissions with federal and provincial funding for jobs creating zero-emissions technologies."