California looks to electric vehicles for grid stability

Protective Relay Training - Basic

Our customized live online or in‑person group training can be delivered to your staff at your location.

- Live Online

- 12 hours Instructor-led

- Group Training Available

California EV V2G explores bi-directional charging, smart charging, and demand response to enhance grid reliability. CPUC, PG&E, and automakers test incentives aligning charging with solar and wind, helping prevent blackouts and curtailment.

Key Points

California EV V2G uses two-way charging and smart incentives to support grid reliability during peak demand.

✅ CPUC studies feasibility, timelines, and cost barriers to V2G

✅ Incentives shift charging to align with solar, wind, off-peak hours

✅ High-cost bidirectional chargers and warranties remain hurdles

California energy regulators are eyeing the power stored in electric vehicles as they hunt for ways to avoid blackouts caused by extreme weather.

While few EV and their charging ports are equipped to deliver electricity back into the grid during emergencies, the California Public Utilities Commission wants more data on it as the agency rules on steps utilities must take to ensure they have enough power for this summer and next year. A draft CPUC decision due to be discussed this week asks about the feasibility of reversing the charge when needed (Energywire, March 8).

“Very few [EVs], maybe a couple of thousand at the most, can give power to the grid, and even fewer are connected into a charger that can do it,” said Gil Tal, director of the Plug-in Hybrid & Electric Vehicle Research Center at the University of California, Davis. EVs that feature the ability “have it at a more experimental level.”

The issue arises as California, where about half of all U.S. EVs are purchased, examines what role the vehicles can play in keeping lights on and refrigerators running and how a much bigger grid will support them in the long term. Even if grid operators can’t pull from EV batteries en masse, experts say cash and other incentives can prompt drivers to shift charging times, boosting grid stability.

“What we can do is not charge the electric cars at times of high demand” such as during heat waves, Tal said.

The EV focus comes after California’s grid manager last summer imposed rolling blackouts when power supplies ran short during a record-shattering heat wave. State energy regulators across the U.S., as EVs challenge state grids, are also looking at their disaster preparedness as Texas recovers from a winter storm last month that cut off electricity for more than 4 million homes and businesses there.

California’s EV efforts can help other states as they add more renewable power to their grids, said Adam Langton, energy services manager at BMW of North America.

That automaker ran a pilot program with San Francisco-based utility Pacific Gas & Electric Co. (PG&E) looking at whether money and other incentives could prompt EV drivers to charge their cars at different times. The payments successfully shifted charging to the middle of the night, when wind power often is plentiful. It also moved some repowering to mornings and early afternoons, when there’s abundant solar energy.

“That can be a tool that the utilities can use to deal with supply issues,” Langton said. “What our research has shown is that vehicles can contribute to [conservation] needs and emergency supply by shifting their charging time.”

Such measures can also help states avoid having to curtail solar production on days when there’s more generation than needed. On many bright days, California has more solar power than it can use.

“As more states add more renewable energy, we think that they’re going to find that EVs complement that really well with smart charging, because grid coordination can get that charging to align with the renewable energy,” Langton said. “It allows to add more and more renewable energy.”

High-cost equipment a hurdle

The CPUC at a future workshop plans to collect information on leveraging EVs to head off power shortages at key times.

But Tal said it will probably take a decade to get enough EVs capable of exporting electricity back to utilities “in high numbers that can make an impact on the grid.”

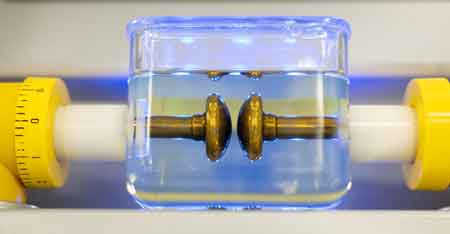

Barriers to reaching such “vehicle to grid” integration are technical and economic, he said. EVs export direct current and need a device on the other side that can convert it to alternating current, similar to a solar power inverter for rooftop panels.

However, the equipment known as a V2G capable charger is costly. It ranges from $4,500 to $5,500, according to a 2017 National Renewable Energy Laboratory report.

PG&E and Los Angeles-based Southern California Edison already have “expressed doubt that short-term measures could be developed in time to expand EV participation by summer 2021” in V2G programs, the draft CPUC proposal said. The utilities suggested instead that the agency encourage EV owners to participate in initiatives where they’d get paid for reducing power consumption or sell electricity back to the grid when needed, known as demand response programs.

Still, almost all major EV automakers are looking at two-directional charging, Tal said.

“The incentive is you can get more value for the car,” he said. “The disincentive is you add more miles in a way on the car,” because an owner would be discharging to the grid and re-charging, and “the battery has limited life.”

And right now, discharging a vehicle to the grid would violate many warranties, he said. Car manufacturers would need to agree to change that and could call for compensation in return.

Meanwhile, San Diego Gas & Electric Co., a Sempra Energy subsidy, plans to launch a pilot looking at delivering power to the grid from electric school buses. The six buses in the pilot transport students in El Cajon, Calif., east of San Diego.

“The buses are perfect because of their big batteries and predictable schedule,” Jessica Packard, SDG&E spokesperson, said in an email. “Ultimately, we hope to scale up and deploy these kinds of innovations throughout our grid in the future.”

She declined to say how much power the buses could deliver because the project isn’t yet operating. It’s set to start later this year.

Mobility needs

While BMW and PG&E did not review vehicle-to-grid power transfers in their own 2017 research ending last year, one study in Delaware did. But it was in a university setting about eight years ago and didn’t look at actual drivers, said Langton with BMW.

In their own findings from the San Francisco Bay Area pilot program, BMW and PG&E found that incentives could quickly change driver behavior in terms of charging.

Technology helps: Most new EVs have timers that allow the driver to control when to charge and when to stop charging. Langton said the pilot program got drivers to have their cars charge from roughly 2 to 6 a.m., when electricity rates typically are lowest.

There can be a lot of solar energy during the day, but in summer, optimum charging times get more complicated in California, he said. People want to run their air conditioners during peak heat hours, so it’s important to be able to get EV drivers to shift to less congested times, he said.

With the right incentives or messaging, Langton said, the pilot persuaded drivers to move charging from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. or noon to 4 p.m. BMW technology allowed for detailed information on battery charge level, ideal charging times and other EV data to be transmitted electronically after plugging in.

The findings are a good first step toward future vehicle-to-grid integration, Langton added.

“One of the things we really pay attention to when we do smart charging is, ‘How does the driver’s mobility needs figure into shifting their charging?'” he said. “We want to make sure that our customers can always do the driving that they need to do.”

The pilot included safeguards such as an opt-out button if the driver wanted to charge immediately. It also made sure the vehicle had a certain level of minimum charge — 15% to 20% — before the delayed smart charging kicked in.

Vehicle-to-grid technology would need to wrestle with the same concepts in a different way. If a car is getting discharged, the driver would want assurances its battery wouldn’t dip below a level that meets their mobility needs, Langton said.

“If that happened even once to a customer, they would probably not want to participate in these programs in the future,” he said.

One group adding charging stations across the country said it isn’t tweaking pricing based on when drivers charge. That’s to help grow EV purchases, said Robert Barrosa, senior director of sales and marketing at Volkswagen AG subsidiary Electrify America, which operates about 450 charging stations in 45 states.

The company has installed battery storage at more than 100 sites to make sure they can provide power at consistent prices even if California or another state calls for energy conservation.

“It’s very important for vehicle adoption that the customer have that,” Barrosa said.

The company could sell that battery storage back to the grid if there are shortfalls, but some market changes are needed first, particularly in California, he said. That’s because the company buys electricity on the retail side but would be sending it back into the wholesale market.

With that cost differential, Barrosa said, “it doesn’t make sense.”