Faraday's Law Explained

By R.W. Hurst, Editor

Faraday’s Law describes electromagnetic induction, where changing magnetic fields generate electricity. Discovered in 1831 by Michael Faraday, it revealed how magnetism produces electric current and became the foundation of modern electrical science.

What is Faraday’s Law?

Faraday's Law is a fundamental principle of electromagnetism describing how a changing magnetic field induces an electromotive force (emf) in a conductor. The law:

✅ Explains electromagnetic induction and induced current

✅ Is essential for transformers, generators, and electric motors

✅ Is the foundation of modern physics and electrical engineering

For a deeper look at the mathematics, mechanisms, and engineering uses, see our detailed guide on Faraday’s Law of Induction."

Michael Faraday, the Inventor of Faraday’s Law

In 1831, Michael Faraday performed experiments with coils of wire, magnets, and galvanometers. He observed that when a magnet was moved through a coil, or when the magnetic field around the coil was changed, a current was generated.

Faraday’s Law proved that electricity could be produced directly from magnetism — a revolutionary concept at the time. Faraday’s experiments were deceptively simple but profoundly important, showing that energy could be converted from one form (mechanical motion of the magnet) into another (electric current).

Theoretical Context

Faraday’s Law provided one of the first clear demonstrations that electricity and magnetism are not separate forces but part of the same phenomenon. This insight was later formalized by James Clerk Maxwell, whose Maxwell’s equations mathematically unified electromagnetism.

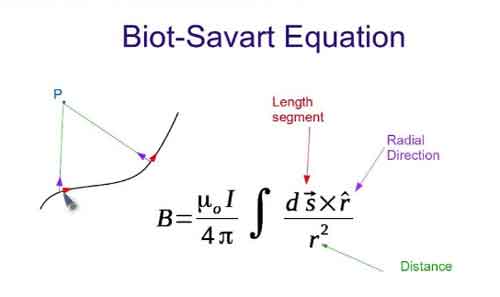

Alongside Ampère’s Law and the Biot–Savart Law, Faraday’s Law gave scientists a new framework to describe the invisible forces of nature. It also introduced the idea of fields, regions of influence surrounding magnets and electrical charges, which became central to modern physics. Read our article titled: Who Invented Electricity for more information about the foundation of electricity.

Understanding Electromagnetic Induction

Faraday’s Law showed that induction can occur in several ways:

-

By moving a conductor through a magnetic field

-

By changing the strength of a magnetic field

-

By altering the orientation or size of the conductor’s loop in the field

In each case, the result is the same: a changing magnetic flux produces an EMF. The direction of the induced current is explained by Lenz’s Law, which states that the induced current always opposes the change that created it, ensuring energy conservation.

The principle of electromagnetic induction is the basis for the operation of various electrical devices, including:

-

Generators: These devices convert mechanical energy into electrical energy by rotating a coil within a magnetic field, causing the magnetic flux to change and inducing an EMF in the coil.

-

Transformers: Transformers work on the principle of mutual induction, where a changing current in the primary coil produces a varying magnetic field, which in turn induces an EMF in the secondary coil.

-

Induction motors: In these motors, a changing magnetic field is created by the stator, inducing an EMF in the rotor conductors, which generates a current that interacts with the magnetic field to produce torque and drive the motor.

Coils, Flux, and Electrodynamics

Faraday’s induction experiments showed that the induced voltage in a coil is equal to the rate of change of magnetic flux through it. This relationship depends on several factors, including the magnetic field strength, the loop area, and the number of turns in the coil. In fact, the induced EMF is proportional to the rate at which a coil of wire cuts across magnetic field lines, meaning that more turns in the coil increase the overall flux linkage.

From the perspective of electrodynamics, this effect illustrates how charges respond to forces within a conductor. The Lorentz force explains why electrons move when exposed to a changing field, while a time-varying field generates a non-conservative electric field that sustains induction. These principles are embedded in the Maxwell–Faraday equation, which extends Faraday’s insight into the framework of Maxwell’s equations.

Faraday also noted that induction is not limited to mutual coupling between separate coils. The principle of self-induction arises when a coil’s own changing current produces an induced EMF opposing the original change. This phenomenon became central to the design of inductors and transformers.

Ultimately, the legacy of Faraday’s Law extends to our understanding of electromagnetic waves. By linking induction with Maxwell’s field theory, Faraday’s Law explains how time-varying fields generate waves that propagate through space — a concept that underpins modern communications and physics.

Why Faraday’s Law Mattered

At the time of its discovery, electricity was known mainly from batteries and static experiments. Faraday’s Law proved that electricity could be generated in continuous and controlled ways. This breakthrough opened the door to inventions that would transform society, from power generation to communication technologies.

Everyday Applications of Faraday’s Law

The importance of Faraday’s Law extends far beyond the laboratory. It forms the basis of countless technologies, including:

-

Electric generators – converting mechanical energy into electrical power.

-

Transformers – enabling efficient power transmission over long distances.

-

Induction motors – powering everything from industrial machines to household appliances.

-

Wireless charging systems – transferring energy without physical connections.

-

Magnetic storage and security – used in swipe cards and sensors.

-

Induction heating and cooktops – converting magnetic energy into heat for practical use.

-

Eddy current braking – providing non-contact braking in trains, amusement rides, and industrial systems by inducing currents that resist motion.

-

Inductors in circuits – storing energy in magnetic fields and controlling current in electrical systems.

-

Wireless energy transfer in EVs – enabling electric vehicles to charge without plugs using electromagnetic induction.

These applications show how Faraday’s 19th-century experiments continue to power the 21st-century world.

Faraday’s Legacy

Faraday’s Law was not just a scientific milestone but also a turning point for technology and industry. Without his insights, there would be no electric power grids, no telecommunications as we know them, and no modern electronics.

The law also highlighted an important principle: that simple experiments can lead to world-changing insights. With little formal education, Faraday reshaped science and technology, showing that careful observation and curiosity could unlock nature’s secrets.

Faraday’s Law remains one of the most important discoveries in physics. By revealing that changing magnetic fields could create electricity, it provided the foundation for modern electrical engineering, industrial power systems, and everyday devices.

Faraday’s Law stands as a reminder that the forces of nature — magnetism, electricity, and motion — are deeply interconnected. Faraday’s insight into electromagnetic induction continues to shape the modern world, demonstrating that a discovery made nearly two centuries ago remains a vital force in our lives today.

Frequently Asked Questions

What did Faraday’s Law prove?

Faraday’s experiments with coils and magnets in 1831 proved that a changing magnetic field can induce an electromotive force (EMF) in a conductor. This showed that electricity can be generated from magnetism, a discovery that revolutionized science and technology.

Why is Faraday’s Law important today?

Faraday’s Law is the foundation of electrical power generation and transmission. It explains how generators, transformers, and induction motors work, making it essential to modern energy systems, communication technologies, and countless everyday devices.

How does Faraday’s Law relate to Maxwell’s equations?

Faraday’s Law was later formalized in Maxwell’s equations as the Maxwell–Faraday equation, which shows that a changing magnetic field produces an electric field. This unification confirmed that electricity and magnetism are two aspects of the same force.