Understanding Current

By R.W. Hurst, Editor

Current is the flow of electric charge in circuits, defined by amperage, driven by voltage, limited by resistance, described by Ohm’s law, and fundamental to AC/DC power systems, loads, conductors, and electronic components.

What Is Current?

Current is charge flow in a circuit, measured in amperes and governed by voltage and resistance.

✅ Measured in amperes; sensed with ammeters and shunts

✅ Defined by Ohm’s law: I = V/R in linear resistive circuits

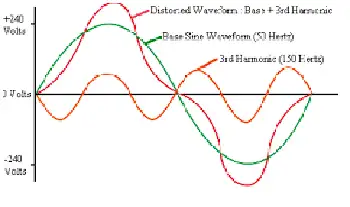

✅ AC alternates; DC is steady; sets power transfer P = V*I

Current is best described as a flow of charge or that the charge is moving. Electrons in motion make up an electric current. This electric current is usually referred to as “current” or “current flow,” no matter how many electrons are moving. Current is a measurement of a rate at which a charge flows through some region of space or a conductor. The moving charges are the free electrons found in conductors, such as copper, silver, aluminum, and gold. The term “free electron” describes a condition in some atoms where the outer electrons are loosely bound to their parent atom. These loosely bound electrons can be easily motivated to move in a given direction when an external source, such as a battery, is applied to the circuit. These electrons are attracted to the positive terminal of the battery, while the negative terminal is the source of the electrons. The greater amount of charge moving through the conductor in a given amount of time translates into a current. For a concise overview of how moving charges create practical circuits, see this guide to current electricity for additional context.

The System International unit for current is the Ampere (A), where

That is, 1 ampere (A) of current is equivalent to 1 coulomb (C) of charge passing through a conductor in 1 second(s). One coulomb of charge equals 6.28 billion billion electrons. The symbol used to indicate current in formulas or on schematics is the capital letter “I.” To explore the formal definition, standards, and measurement practices, consult this explanation of the ampere for deeper detail.

When current flow is one direction, it is called direct current (DC). Later in the text, we will discuss the form of current that periodically oscillates back and forth within the circuit. The present discussion will only be concerned with the use of direct current. If you are working with batteries or electronic devices, you will encounter direct current (DC) in most basic circuits.

The velocity of the charge is actually an average velocity and is called drift velocity. To understand the idea of drift velocity, think of a conductor in which the charge carriers are free electrons. These electrons are always in a state of random motion similar to that of gas molecules. When a voltage is applied across the conductor, an electromotive force creates an electric field within the conductor and a current is established. The electrons do not move in a straight direction but undergo repeated collisions with other nearby atoms. These collisions usually knock other free electrons from their atoms, and these electrons move on toward the positive end of the conductor with an average velocity called the drift velocity, which is relatively a slow speed. To understand the nearly instantaneous speed of the effect of the current, it is helpful to visualize a long tube filled with steel balls as shown in Figure 10-37. It can be seen that a ball introduced in one end of the tube, which represents the conductor, will immediately cause a ball to be emitted at the opposite end of the tube. Thus, electric current can be viewed as instantaneous, even though it is the result of a relatively slow drift of electrons. For foundational concepts that connect drift velocity with circuit behavior, review this basic electricity primer to reinforce the fundamentals.

Current is also a physical quantity that can be measured and expressed numerically in amperes. Electric current can be compared to the flow of water in a pipe. It is measureda at the rate in which a charge flows past a certain point on a circuit. Current in a circuit can be measured if the quantity of charge "Q" passing through a cross section of a wire in a time "t" (time) can be measured. The current is simply the ratio of the quantity of charge and time. Understanding current and charge flow also clarifies how circuits deliver electrical energy to perform useful work.

Electrical current is essentially an electric charge in motion. It can take either the form of a sudden discharge of static electricity, such as a lightning bolt or a spark between your finger and a ground light switch plate. More commonly, though, when we speak of current, we mean the more controlled form of electricity from generators, batteries, solar cells or fuel cells. A helpful overview of static, current, and related phenomena is available in this summary of electricity types for quick reference.

We can think of the flow of electrons in a wire as the flow of water in a pipe, except in this case, the pipe of water is always full. If the valve on the pipe is opened at one end to let water into the pipe, one doesn't have to wait for that water to make its way all the way to the other end of the pipe. We get water out the other end almost instantaneously because the incoming water pushes the water that's already in the pipe toward the end. This is what happens in the case of electrical current in a wire. The conduction electrons are already present in the wire; we just need to start pushing electrons in one end, and they start flowing at the other end instantly. In household power systems, that push on conduction electrons alternates in direction as alternating current (AC) drives the flow with a time-varying voltage.

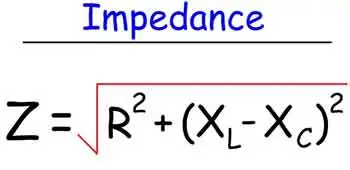

Current Formula

Current is rate of flow of negatively-charged particles, called electrons, through a predetermined cross-sectional area in a conductor.

Essentially, flow of electrons in an electric circuit leads to the establishment of current.

q = relatively charged electrons (C)

t = Time

Amp = C/sec

Often measured in milliamps, mA