What is an Arc Fault?

By R.W. Hurst, Editor

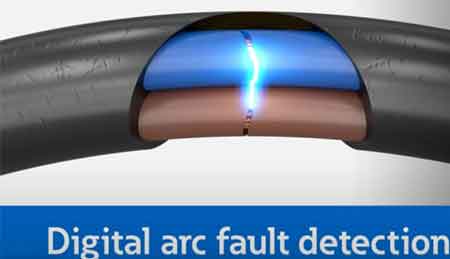

An arc fault is a dangerous electrical discharge between conductors or to ground. It generates intense heat and light, often caused by damaged insulation, frayed wires, or loose connections, posing major electrical safety and fire hazards.

What is an Arc Fault?

An arc fault is an unintended electrical discharge that occurs when insulation or wiring fails, producing dangerous heat that can ignite fires and damage circuits.

✅ Caused by frayed wires or loose connections

✅ Produces intense heat and light energy

✅ Prevented by Arc Fault Circuit Interrupters (AFCIs)

Basic Protection Relay Training

Request a Free Training Quotation

Understanding Arc Faults and Electrical Safety

An arc fault is a hazardous electrical event that can lead to severe consequences, including fires and substantial property damage. Understanding how faults occur, how to prevent them, and why protective measures like Arc Fault Circuit Interrupters (AFCIs) are essential can significantly improve home and workplace safety.

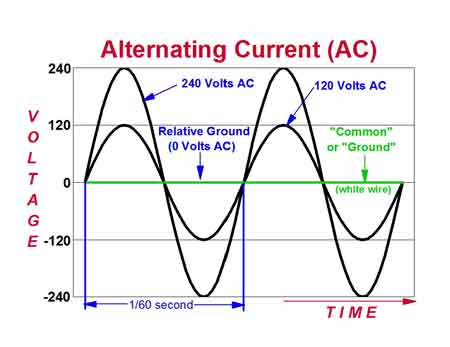

When electrical current jumps across a gap or an unintended path, it forms an electric arc. This arc generates extremely high temperatures—often exceeding 10,000°F—capable of igniting nearby insulation, wood framing, or other combustible materials. Faults are typically caused by damaged, frayed, or aging wiring, loose terminal connections, or punctured cables from nails and screws during construction. For more insight into advanced safety devices, learn how an arc fault interrupter breaker detects hazardous arcing and disconnects power before a fire can start.

Arc fault protection is especially important in areas where people live and spend time, such as family rooms, dining rooms, and living rooms, where electrical wiring runs behind walls containing materials such as wood framing or insulation that can easily ignite. Modern safety standards, as mandated by the National Electrical Code, require the installation of Arc Fault Circuit Interrupters (AFCIs) in these spaces to prevent fires caused by faults. When combined with Ground Fault Circuit Interrupters, which protect against electrical shock, AFCIs provide comprehensive protection against both fire and shock hazards in residential and commercial environments.

Types of Arc Faults

Arc faults can appear in different forms, each with its own risks and detection requirements:

-

Series Faults – Occur along a single conductor, usually from a broken wire or loose terminal. These arcs produce less current but can still ignite fires.

-

Parallel Faults – Form between two conductors (hot-to-neutral or hot-to-ground). These faults create higher current levels and more intense arcing.

-

Ground Faults – Happen when current leaks or shorts to a grounded surface, such as a metal outlet box or appliance casing. Explore how ground fault protection complements AFCIs by guarding against current leakage that could cause electric shock or parallel arc conditions.

Recognizing these types helps electricians and inspectors identify the right protection strategies and select appropriate AFCI devices. To see how fault current behavior impacts fault risks, review our explanation of available fault current and why accurate short-circuit studies are essential for system safety.

How AFCI Detection Works

AFCIs are intelligent safety devices designed to detect the unique electrical signatures of faults. They continuously monitor current waveforms and frequencies, distinguishing dangerous arcs from normal switching arcs (such as those produced by light switches or vacuum cleaners).

When an AFCI identifies an abnormal frequency pattern consistent with arcing, it trips the circuit within milliseconds—disconnecting power before the fault can ignite a fire. This advanced “signature detection” technology is required by modern safety codes and has saved countless lives and properties. For more insight into advanced safety devices, learn how an arc fault interrupter breaker detects hazardous arcing and disconnects power before a fire can start.

Limitations and Nuisance Tripping

While AFCIs are highly effective, they can occasionally cause nuisance tripping. This occurs when the device misinterprets harmless electrical noise as a fault, typically triggered by motors, dimmers, or other electronic devices. Regular inspection, proper grounding, and updated AFCI models help minimize these false positives. If nuisance tripping persists, it’s advisable to have an electrician verify circuit wiring and device compatibility. To understand how electrical systems respond to fault conditions, refer to our detailed explanation of protective relay coordination, which ensures that circuit breakers isolate faults without disrupting unaffected circuits.

Code Requirements and Standards

Arc fault protection is mandated by both U.S. and Canadian electrical codes:

-

National Electrical Code (NEC 210.12) requires AFCI protection for all 120-volt, single-phase, 15- and 20-amp branch circuits supplying living areas such as bedrooms, family rooms, dining rooms, and similar spaces.

-

Canadian Electrical Code (CEC Section 26) similarly mandates AFCI in dwelling units.

-

IEEE 1584 provides calculation guidelines for flash hazards in industrial power systems, complementing residential and commercial fault safety standards.

Following these standards ensures compliance and dramatically reduces fire risks across residential, commercial, and industrial applications.

Statistics and Case Studies

According to the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC), electrical fires cause over 51,000 residential fires annually, resulting in more than 500 deaths and $1.3 billion in property damage. Studies show that AFCI protection can prevent more than half of these incidents, highlighting its critical role in modern electrical safety systems.

Emerging Technologies in Arc Fault Detection

New generations of AFCIs utilize microprocessors and artificial intelligence to enhance accuracy and minimize false trips. These smart devices analyze waveform patterns with greater precision, detecting high-impedance arcs and subtle irregularities. Future technologies may integrate predictive analytics and IoT monitoring to diagnose potential faults before they become hazards. Finally, explore comprehensive methods of electrical surge protection, which safeguard sensitive equipment from voltage spikes often linked to lightning events.

Common Causes of Arc Faults

-

Damaged or aging electrical wiring

-

Loose terminal connections in outlets or switches

-

Overloaded circuits or faulty appliances

-

Nails or screws penetrating electrical cables

-

Deteriorated insulation from heat, moisture, or rodents

Regular maintenance and periodic inspections by a licensed electrician are essential preventive measures.

Arc Fault vs Ground Fault vs Short Circuit

| Fault Type | Description | Main Hazard | Protection Device |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arc Fault | Unintended arcing between conductors or within wiring | Fire risk | AFCI |

| Ground Fault | Current flowing to ground unintentionally | Electric shock | GFCI |

| Short Circuit | Direct contact between conductors | High current / equipment damage | Circuit Breaker |

Understanding these differences helps ensure that electrical protection systems are properly matched to the specific hazards they are intended to address.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why does my AFCI keep tripping?

Often due to electronic interference, shared neutrals, or actual wiring issues. Replace outdated AFCIs and consult a professional if tripping persists.

Can I retrofit AFCIs into older panels?

Yes. AFCI breakers can replace standard breakers in most modern panels. Have a qualified electrician confirm compatibility before installation.

Are AFCIs required everywhere?

While required in most living spaces, some regions exempt areas like garages or unfinished basements. Check the NEC or CEC requirements for your jurisdiction.

Related Articles