Latest Electrical Transformers Articles

Control Transformer Explained

A control transformer provides a stable voltage to control circuits in industrial and commercial applications. It ensures reliable performance of contactors, relays, and motor starters by stepping down line voltage for safe, consistent control system operation.

What is a Control Transformer?

A control transformer is a type of transformer used to supply voltage to control devices in electrical systems.

✅ Provides consistent voltage for control circuits and devices

✅ Supports relays, contactors, timers, and PLCs

✅ Ideal for industrial machines and automation systems

Electrical Transformer Maintenance Training

Substation Maintenance Training

Request a Free Training Quotation

It is designed to provide a stable voltage for control circuits in various applications. This equipment reduces the supply voltage to a lower, more manageable level, suitable for controlling machinery and other electrical devices. Typically, the primary voltage is high, while the secondary voltage is lower, providing the necessary power for systems without compromising safety. Unlike a current transformer, which is used for measurement and protection, a control transformer focuses on delivering reliable voltage for circuits.

The working principle of these units is straightforward. When alternating current flows through the primary winding, it creates a magnetic field that induces a current in the secondary winding. This induced current has a lower voltage, specifically tailored to the needs of control circuits, ensuring consistent and reliable operation of the equipment. For a broader context on energy regulation, see our overview of what is a transformer, which explains how these devices manage voltage in power and systems.

Understanding The Control Transformer

Control transformers are specifically designed to step down the higher voltage from the main power supply to a lower, safer voltage level suitable for control circuits. These circuits are responsible for operating various devices such as relays, contactors, solenoids, and other equipment. Many industrial facilities also pair control transformers with dry type transformers, which offer durability and safety in environments where oil-filled designs are not suitable.

These devices typically operate at lower voltages, usually between 24V and 240V. Control power transformers provide the necessary voltage transformation to ensure the safe and efficient operation of these types of circuits. Discover how step down transformers safely reduce voltage, a principle commonly applied in most control transformer designs for circuit protection.

Construction and Design

Control power transformers are typically constructed with a laminated steel core and two or more windings. The primary winding is connected to the main power supply, while the secondary winding provides the lower voltage output for the circuits.

The design considers various factors, including the required secondary voltage, power rating, and insulation requirements. They are often designed to withstand harsh industrial environments and offer protection against short circuits and overloads.

Key Features and Benefits

They offer several features and benefits that make them indispensable in industrial settings:

-

Safety: The primary function is to provide a safe voltage level for circuits, protecting personnel and equipment from electrical hazards.

-

Reliability: These units are designed to be rugged and reliable, ensuring consistent power delivery to circuits even in demanding conditions.

-

Efficiency: They are engineered to be highly efficient, minimizing energy losses and reducing operating costs.

-

Versatility: They are available in a wide range of voltage and power ratings, making them suitable for various industrial applications.

-

Compact Design: Many units are designed to be compact and space-saving, making them easy to install in confined spaces.

Key Differences Between a Control Transformer and a Power Transformer

While both types serve to transfer electrical energy from one circuit to another, they are distinct in their applications and design. Control power transformers are primarily used to supply power to circuits, whereas power transformers are designed for high-voltage transmission and distribution in electrical grids. Understand different types of devicess to see how they fit into the broader equipment ecosystem, including power, potential, and isolation types.

One key difference lies in the voltage regulation. They offer better voltage regulation, which is crucial for sensitive circuits that require a stable and precise secondary voltage. In contrast, power transformers are optimized for efficiency and capacity, often dealing with much higher power levels.

Additionally, they are designed to handle inrush currents that occur when control devices, such as relays and solenoids, are activated. This ability to manage sudden surges in current makes them ideal for industrial environments where control stability is paramount. If you’re comparing applications, our page on power transformers contrasts with control transformers by focusing on high-voltage transmission and grid distribution.

Typical Applications

Control transformers are widely used in various industrial settings. Some of the typical applications include:

-

Machine Tool: These units provide stable voltage to control circuits in machine tools, ensuring precise operation and safety.

-

HVAC Systems: These systems utilize electrical components to power circuits that regulate temperature and airflow in heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems.

-

Lighting: In commercial and industrial lighting systems, they help manage the circuits for switching and dimming lights.

-

Motors: They are essential in motor centers, providing the necessary voltage for relays and contactors that start and stop motors.

For comparison, an isolation transformer provides electrical separation and safety, whereas a control transformer specializes in stable voltage regulation for control equipment.

Selecting the Right One

Choosing the appropriate device requires careful consideration of several factors:

-

Voltage Requirements: Determine the primary and secondary voltage levels needed for your application. The secondary voltage should match the requirements of the circuit.

-

Power Rating: Assess the power demand of the circuit and select a unit that can handle the load. The power rating is usually specified in volt-amperes (VA).

-

Inrush Current: Consider the inrush current capacity, especially if the circuit includes components such as relays or solenoids that draw high currents at startup.

-

Environmental Conditions: Ensure the unit is suitable for the operating environment, considering factors such as temperature, humidity, and exposure to dust or chemicals.

-

Regulation and Efficiency: Choose a unit that offers good voltage regulation and efficiency to ensure reliable performance.

For a more detailed look at specialized devices, visit our page on the potential transformer, which also converts voltage but for measurement purposes.

Common Issues and Troubleshooting Steps

Despite their robustness, they can encounter issues. Some common problems include:

-

Overheating: This can occur due to excessive load or poor ventilation. To address this, ensure the device is not overloaded and that it has adequate cooling.

-

Voltage Fluctuations: Inconsistent secondary voltage can result from poor connections or a failing unit. Check all connections and replace the equipment if necessary.

-

Short Circuits: A short circuit in the circuit can cause the unit to fail. Inspect the circuit for faults and repair any damaged components.

-

Noise: Unusual noises often indicate loose laminations or hardware. Tighten any loose parts and ensure the device is securely mounted.

A control transformer is vital in industrial settings, providing stable and reliable voltage to circuits. Understanding their working principles, applications, and differences from power transformers is crucial for selecting the right equipment for your needs. By addressing common issues and following proper troubleshooting steps, you can ensure the longevity and efficiency of your industrial systems, maintaining their smooth operation. Discover how transformer systems operate in real-world applications with our comprehensive resource on what is a transformer, which explains their design, function, and industrial applications.

Related Articles

Sign Up for Electricity Forum’s Electrical Transformers Newsletter

Stay informed with our FREE Electrical Transformers Newsletter — get the latest news, breakthrough technologies, and expert insights, delivered straight to your inbox.

What is Core Balance Current Transformer?

Core Balance Current Transformer (CBCT) detects earth leakage, residual current, and ground faults. It safeguards electrical distribution, prevents equipment damage, and enhances worker safety by detecting faults and operating protective relays.

What is Core Balance Current Transformer

A Core Balance Current Transformer (CBCT) is a protective device that detects leakage or residual current in power systems, ensuring safety and reliability.

✅ Provides ground fault protection in electrical networks

✅ Enhances insulation monitoring and system safety

✅ Supports reliable fault detection and energy distribution

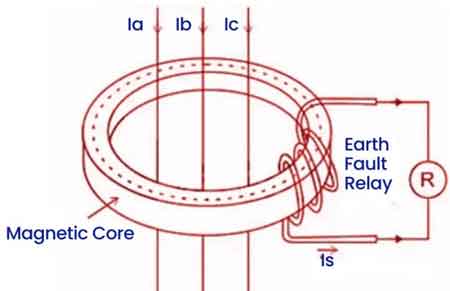

A Core Balance Current Transformer (CBCT) is a protective device that senses leakage or residual current in power systems. Operating on the zero-sequence current principle, CBCTs improve ground fault protection, activate earth fault relays, and support compliance with safety standards in industrial and utility applications. For a broader perspective on transformer technology, visit our Utility Transformers Channel covering design, function, and safety applications.

CBCTs play a critical role in enhancing safety and minimizing equipment damage in industrial settings, where precision and rapid fault detection are essential. By identifying earth leakage and earth fault conditions, CBCTs protect electrical power systems, ensuring safety for electrical workers and reducing downtime due to potential faults. Understanding the working principle and applications of CBCTs helps professionals maintain efficient and safe electrical operations. Many CBCTs are installed alongside distribution transformers to provide ground fault protection in medium-voltage systems.

Electrical Transformer Maintenance Training

Substation Maintenance Training

Request a Free Training Quotation

Key Differences Between Core Balance Current Transformer and Regular Current Transformers (CT)

While a regular CT provides current measurement for metering and protective systems, a CBCT specializes in identifying current imbalance and earth faults, making it indispensable for residual current detection in safety-critical environments. A regular current transformer monitors the magnitude of current flowing through a circuit, offering measurements used for metering and general protection. CBCTs, on the other hand, are dedicated to detecting earth faults by identifying current imbalances within a three-phase system. Unlike standard CTs, CBCTs rely on a secondary winding through which the three-phase conductors pass, providing a balanced system under normal conditions. When an imbalance occurs, indicating a potential fault, the CBCT detects it and signals protective devices to address the issue. To understand how three-phase systems interact with protective devices like CBCTs, see our guide on 3-phase transformers.

Applications and Benefits of Core Balance Current Transformer

Core Balance Current Transformers are essential in applications where earth fault protection is critical. These transformers are typically used in industrial motors and medium-voltage electrical systems, where the risk of earth leakage or fault can have significant consequences. The CBCT design allows it to promptly detect and relay information about imbalances, enhancing operational safety. Electrical workers benefit from CBCTs because they reduce the risk of equipment damage, protect personnel from electrical hazards, and help maintain compliance with safety regulations in sensitive environments. Residual current detection is critical for electrical substation transformers, where earth faults can compromise large-scale power reliability.

Working Principle of Core Balance Current Transformer

The CBCT functions on the zero-sequence current principle, which is similar to Kirchhoff’s Current Law. In balanced conditions, the sum of the three-phase currents (Ia + Ib + Ic) equals zero. This results in no magnetic flux in the CBCT core, leaving the secondary winding unaffected. However, when a ground fault or earth leakage disrupts the balance, a residual or zero-sequence current is generated. This current flows through the CBCT’s secondary winding, triggering the earth fault relay to isolate the system. This action minimizes the potential for electrical fires, equipment damage, or personnel injury. CBCTs are widely applied in motor feeders, switchgear assemblies, and cable systems to detect earth leakage early, reducing arc flash hazards and insulation failures. Their use supports safety compliance and helps facilities maintain uptime in energy-intensive operations. The role of CBCTs complements protective strategies such as transformer overcurrent protection, ensuring systems remain safe and stable.

CBCT Features and Selection Criteria

Core Balance Current Transformers are chosen for their high sensitivity, reliability, and ease of installation. Key characteristics include a nominal CT ratio adequate to detect even minor ground faults, a minimal ground leakage current requirement, and sufficient knee voltage to activate the earth fault relay. Choosing a CBCT with the correct internal diameter ensures compatibility with the specific cable size in use. These transformers must also provide consistent performance, ensuring protection across various industrial applications where electrical power safety is paramount.

Selection depends on the accuracy of CT ratio, sensitivity to low fault currents, proper relay coordination, and compatibility with cable diameters. Easy installation and low maintenance also make CBCTs practical for long-term industrial safety strategies.

CBCTs are invaluable in industrial and medium-voltage applications for their unique ability to detect ground faults and earth leakages that could compromise electrical systems. By utilizing a zero-sequence current detection method, CBCTs offer rapid and reliable protection against faults, enhancing the safety and integrity of electrical systems. This makes CBCTs a crucial tool for electrical workers, contributing to safer work environments and extending the life of equipment.

Frequently Asked Questions

How Does a Core Balance Current Transformer Detect Ground Faults?

CBCTs operate on the principle of zero-sequence current balance, meaning they detect residual current that arises when there's an imbalance among the phases in a three-phase system. Normally, the vector sum of the currents in each phase is zero, indicating balanced conditions without any earth leakage or fault. When an earth fault or leakage occurs, however, this balance is disrupted, resulting in residual current. The CBCT’s secondary winding, connected to an earth fault relay, registers this current and activates the relay. This detection triggers safety mechanisms to isolate the faulty circuit, minimizing risks associated with fault conditions. For insight into how transformer performance is monitored, explore condition monitoring in an age of modernization.

Where is a Core Balance Current Transformer used?

A Core Balance Current Transformer (CBCT) is widely used in industrial plants, medium-voltage switchgear, motor feeders, and cable systems. It provides earth fault detection, residual current monitoring, and insulation protection in environments where electrical safety and reliability are critical.

What is the difference between CBCT and Earth Leakage Relay?

A CBCT detects residual or leakage current caused by an imbalance in a three-phase system, while an Earth Leakage Relay (ELR) is the protective device that receives the CBCT signal and trips the circuit. Together, they provide effective earth fault protection and system safety.

Related Articles

Earthing Transformer - Safety and Stability

An earthing transformer provides grounding for ungrounded systems, enabling a safe path for fault current, maintaining voltage stability, and protecting equipment. It supports neutral grounding, arc suppression, and safe distribution in industrial power networks.

What is an Earthing Transformer?

An earthing transformer is a special transformer that provides a neutral point to ungrounded electrical systems, ensuring fault current management, stability, and safety.

✅ Provides grounding for ungrounded power systems

✅ Enables safe fault current dissipation and arc suppression

✅ Improves voltage stability and equipment protection

An earthing transformer is a critical component in an electrical power system, ensuring its safety and stability by providing a solid connection between the system's neutral point and earth. For an industrial electrician, understanding the principles and applications is essential for ensuring the reliable and safe operation of electrical equipment. Let’s explore its technical role, methods, and practical benefits. For a broader understanding of how grounding devices integrate into power networks, see our overview of grounding transformers.

Electrical Transformer Maintenance Training

Substation Maintenance Training

Request a Free Training Quotation

Technical Role of an Earthing Transformer

Problem: Delta Systems lacks a Neutral

In many power networks, particularly those utilizing delta-connected systems, there is no inherent neutral point. Without a neutral, the system cannot be properly grounded, leaving it vulnerable to dangerous voltage rises, unstable operation, and uncontrolled fault currents. Many earthing applications are tied to distribution transformers, which step down voltage while maintaining safe and stable system operation.

Solution: Earthing Transformer Creates a Neutral Point

An earthing transformer solves this issue by generating an artificial neutral. Once connected to earth, this neutral point allows fault currents to flow safely, prevents overvoltages during earth faults, and stabilizes the system during disturbances. To understand the wider role of these devices in substations, explore our guide to the electrical substation transformer.

Method: Zigzag Winding Cancels Zero-Sequence Currents

The most common earthing transformer design uses a zigzag winding configuration. By arranging the windings to oppose each other, the transformer cancels out zero-sequence currents—those responsible for ground fault conditions—while maintaining a stable neutral reference. This reduces the magnitude of fault currents and improves system stability.

Benefit: Safety, Stability, and Equipment Protection

With a low-impedance path for fault currents, earthing transformers limit fault damage, protect sensitive equipment, and safeguard personnel. They also ensure balanced voltages across the system, reduce arc flash hazards, and support an uninterrupted power supply in industrial and utility environments.

Comparisons and Variants

Earthing Transformer vs Grounding Resistor

While an earthing transformer provides a neutral point for grounding, a grounding resistor limits the magnitude of fault current by inserting resistance into the neutral-to-ground connection. Transformers are used when no neutral exists, while resistors are applied when a neutral is available but current limiting is required. The structural aspects of transformer design, including cores and windings, are explained in our resource on transformer components.

Zigzag vs Wye Connection

Zigzag-connected earthing transformers are more effective at handling unbalanced loads and cancelling zero-sequence currents, making them ideal for fault protection. Wye-connected grounding transformers, though simpler, are less effective in balancing ungrounded systems and are less common in modern networks. Industrial systems often combine earthing transformers with medium voltage transformers to achieve both fault current protection and reliable power supply.

When to Use an Earthing Transformer vs a Directly Grounded Neutral

In systems with a natural neutral, direct grounding is often simpler and more economical. However, when no neutral exists—as in delta or certain generator systems—an earthing transformer becomes essential. It not only provides the missing neutral but also enhances fault control and voltage stability.

Transformer Earthing Diagram

A transformer earthing diagram visually represents the connection between a transformer and the earth, illustrating how it provides a path for fault currents to safely flow to ground. This diagram typically shows the transformer's windings, the connection to the system neutral, and the earthing connection.

Different configurations, such as zigzag or wye connections, can be depicted in the diagram to illustrate how the transformer creates an artificial neutral point in systems where one isn’t available. These diagrams are essential tools for engineers and electricians to understand the earthing transformer’s role in protecting equipment, maintaining system stability, and ensuring personnel safety during fault conditions.

Power System Stability

Maintaining power system stability is crucial for ensuring a reliable electricity supply. Earthing transformers contribute by providing a stable neutral point and limiting fault currents. This helps to prevent voltage fluctuations and maintain balanced voltages across the system, even during disturbances. By ensuring a stable operating environment, earthing transformers help prevent outages and support the reliable delivery of electricity to consumers.

An earthing transformer is more than a grounding device—it is a safeguard for reliable, efficient, and safe electrical networks. By creating a neutral point, limiting fault currents, and stabilizing voltages, it protects equipment, ensures worker safety, and keeps industrial and utility power systems operating without interruption.

Related Articles

Portable Current Transformer - Essential Electrician Tool

Portable current transformer for clamp-on CT testing, temporary metering, and power monitoring; supports AC/DC measurement, handheld diagnostics, IEC accuracy classes, flexible Rogowski coils, and safe, non-intrusive load studies in industrial maintenance.

Understanding How a Portable Current Transformer Works

A portable current transformer (PCT) provides a reliable way to measure and monitor electrical flow in challenging environments. Understanding this tool is crucial for maintaining safety, optimizing system performance, and ensuring compliance with strict industry regulations. In modern electrical engineering, PCT has become an indispensable tool for precision monitoring and measuring electrical systems. Compact, reliable, and versatile, this device is designed to provide accurate electrical flow readings while maintaining ease of transport and installation. Its use spans a range of applications, from diagnosing electrical faults to monitoring power consumption in industrial and residential settings. For foundational context, see the overview of what a current transformer is and how it relates to portable designs for field measurements.

Electrical Transformer Maintenance Training

Substation Maintenance Training

Request a Free Training Quotation

The Convenience of Clamp-On Designs

One of the defining features of PCT is its ability to combine functionality with mobility. Traditional transformers often require significant installation effort due to their bulky nature and fixed configurations. In contrast, portable models, including the widely popular clamp-on current transformer, eliminate the need for complex wiring or system shutdowns. The clamp-on design allows engineers to measure by simply attaching the transformer to a conductor, offering unparalleled convenience and efficiency. This capability is particularly advantageous when time and accessibility are critical factors. Clamp-on units are a subset of the broader family of current transformers that enable non-intrusive measurements during commissioning work.

Innovative Split-Core Technology

The adaptability of PCT is further enhanced by innovations like the split-core design. Unlike conventional solid-core transformers, split-core models can be opened and fitted around an existing conductor without the need to disconnect or reroute cables. This makes them ideal for retrofitting projects and temporary monitoring setups. Moreover, the lightweight and compact nature of split-core PCTs ensures they are easy to handle, even in confined or hard-to-reach locations. For applications involving leakage and earth-fault detection, engineers often reference the core-balance current transformer concept to validate installation choices.

Reliable Power Supply for Flexibility

A reliable power supply is another essential component that ensures the effective functioning of a PCT. These devices typically require minimal power to operate, making them compatible with battery packs or other portable energy sources. This feature is especially useful in fieldwork or remote areas where access to a stable electrical grid may be limited. The ability to rely on portable power solutions adds to the versatility and practicality of these transformers, further cementing their value in a wide range of applications. In portable test kits, PCTs are considered part of the wider class of instrument transformers that condition signals for safe metering in the field.

Driving Energy Efficiency with Real-Time Insights

PCTs also play a pivotal role in the growing demand for energy efficiency. With the increasing emphasis on monitoring and optimizing power usage, these devices provide real-time insights into electrical consumption patterns. Their ability to measure high accuracy without disrupting operations enables industries to identify inefficiencies and implement solutions to reduce energy waste. In this context, PCTs contribute to both cost savings and environmental sustainability. Selecting an appropriate current transformer ratio ensures readings remain within instrument range while maintaining accuracy at typical load currents.

The Role of Digital Technology in Modern PCTs

The integration of digital technologies has further revolutionized the capabilities of PCT. Many modern models come equipped with features such as wireless data transmission and advanced analytics. These capabilities allow users to monitor electrical systems remotely and gain deeper insights into system performance. By combining portability with cutting-edge technology, PCTs continue to evolve in ways that meet the demands of an increasingly connected and data-driven world. Before deployment, teams often validate sensor behavior with a current transformer simulation to anticipate saturation and dynamic response under transients.

Frequently Asked Questions

What does a portable current transformer do?

A PCT is used to measure the electrical flowing through an electrical circuit without making direct electrical contact. It works by converting the high electrical flow from the primary conductor into a proportional, lower electrical flow in its secondary winding, allowing it to be safely measured with standard instruments like ammeters or voltmeters. This is particularly useful for industrial electricians who need to measure electrical flow in live systems, offering a safe, non-invasive method for monitoring electrical systems. This function differs from a potential transformer, which scales voltage for measurement rather than electrical flow in similar monitoring scenarios.

How to make a portable current transformer at home?

Making a PCT at home requires basic components and some knowledge of electrical theory. Here’s a simple method:

- Core material: Use a magnetic core, typically a ferrite or iron core, that can handle the magnetic flux.

- Primary coil: The primary conductor is either passed through the core or wrapped around it. The primary coil may be a single turn or just the wire you want to measure.

- Secondary coil: Wind several turns of insulated wire around the core. The number of turns determines the electrical flow transformation ratio (e.g., a 1:100 ratio means 100 turns in the secondary for every turn in the primary).

- Insulation: Proper insulation between the primary and secondary coils is necessary to prevent electrical hazards.

- Once assembled, you can connect the secondary coil to a measurement device like an ammeter to measure the electrical flow through the primary conductor.

How to select the right PCT for electrical measurements?

When selecting the right PCT for electrical measurements, it's important to consider several key factors. First, determine the electrical flow rating based on the maximum electrical flow expected in the circuit. Ensure the CT can handle this without exceeding its capacity. Accuracy is another critical factor; choose a CT that meets the precision required for your specific measurements. The rated burden of the CT should also be matched to the measurement instrument’s input impedance to ensure accurate readings. Additionally, consider the size and portability—if you're working in a confined space or need to carry the CT to various locations, look for a lightweight and compact model. Finally, select the appropriate core type, such as wound, split-core, or toroidal, based on your installation needs, whether you require a permanent setup or one that can be easily clamped around live conductors.

What are the safety precautions when using a portable current transformer?

Using a PCT safely requires taking specific precautions. First, ensure the CT has proper insulation to avoid accidental contact with live electrical components. Always check that the CT is rated for the voltage and electrical flow of your system to prevent overloading, which could damage the device or cause hazardous conditions. When working with a portable CT, never open the secondary circuit under load, as this can generate dangerous high voltages. Additionally, always ground the secondary side of the CT to reduce the risk of electric shock. Wear appropriate protective gear, such as insulated gloves and rubber mats, to prevent accidents, and inspect the CT for any visible damage before use. Following these precautions ensures the safe operation of the portable CT and minimizes the risk of electrical hazards.

What are the advantages of using a PCT?

The use of a PCT offers several key advantages. One of the main benefits is safety—portable CTs allow electricians to measure electrical flow in live circuits without direct contact, reducing the risk of electrical shock. These devices are also highly portable, making them easy to transport and use in different environments, whether for temporary monitoring, diagnostics, or maintenance tasks. Portable CTs are non-invasive, particularly split-core types, which can be easily clamped around existing wiring without disconnecting the circuit. This feature saves time and avoids system downtime. Moreover, portable CTs are generally cost-effective for applications that require occasional measurements, as they provide a more affordable alternative to permanent electrical flow. Finally, their versatility makes them suitable for a range of applications, from industrial machinery and commercial buildings to residential systems.

A PCT is a compact, lightweight device used for measuring electrical flow in various applications. It is designed to be easily carried and applied in field settings or temporary installations, making it ideal for situations where a permanent CT installation is impractical. PCTs are commonly used in the maintenance, testing, and troubleshooting of electrical systems. They function by encircling a conductor and transforming the high electrical flow into a lower, measurable value, which can be safely monitored using standard instruments. Their portability and ease of use make them essential tools for electrical professionals.

Related Articles

Isolation Transformer

An isolation transformer provides electrical separation between the primary and secondary windings, enhancing safety, reducing noise, and protecting equipment. Commonly used in sensitive electronics, medical devices, and industrial systems, it prevents ground loops and ensures stable power quality.

What is an Isolation Transformer?

An isolation transformer plays a crucial role in ensuring the safety and optimal performance of electrical systems across various industries.

✅ Provides galvanic isolation between input and output circuits.

✅ Reduces electrical noise and prevents ground loop interference.

✅ Protects sensitive equipment from power surges and faults.

Its ability to provide electrical isolation, voltage conversion, noise reduction, and enhanced power supply stability makes it an essential component in modern electronic applications. By understanding its functions and benefits, we can appreciate its invaluable contribution to electrical power systems.

Electrical Transformer Maintenance Training

Substation Maintenance Training

Request a Free Training Quotation

At the heart of electrical safety is the concept of electrical isolation, which involves separating electrical circuits to prevent the flow of current between them. This is crucial in minimizing the risk of electrical shock and preventing potential damage to equipment. An isolation transformer achieves this by having primary and secondary windings with no direct electrical connection, transferring energy through magnetic induction. This process ensures galvanic separation, which protects sensitive equipment from potential harm. To understand how electrical energy is converted between voltage levels, see our guide on what is a transformer.

Dry isolation transformers are widely used in commercial and industrial systems where safety and performance are critical. A galvanic isolation transformer prevents direct electrical connection, improving protection and reliability. Isolation transformers offer reduced noise disruption, making them valuable for sensitive equipment in hospitals, laboratories, and data centers. Different types of isolation transformers are available, including the ultra isolation transformer, which provides maximum suppression of transients and harmonics for the most demanding applications.

Noise Reduction and EMI Protection

An Isolation transformer is crucial in noise reduction, breaking ground loops and minimizing common-mode noise. Ground loops occur when an undesired electrical path between two points at different voltage levels causes interference and noise in electronic equipment. Isolating the power supply from the equipment breaks ground loops and enhances the performance of sensitive devices. Additionally, an isolation transformer helps reduce electromagnetic interference (EMI) and radio frequency interference (RFI), collectively referred to as EMC protection. If you're interested in how current levels are measured, check out our article on current transformers.

Key Differences Between Isolation Transformers and Other Types

| Feature | Isolation Transformer | Step-Up/Step-Down Transformer | Autotransformer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Provides galvanic isolation and safety | Changes voltage levels (increase/decrease) | Changes voltage with partial isolation |

| Electrical Connection | No direct connection between windings | Directly coupled for voltage conversion | Shares common winding |

| Noise Reduction | Excellent (blocks EMI/RFI, ground loops) | Limited noise suppression | Minimal noise suppression |

| Voltage Regulation | Moderate, focuses on isolation | High, designed for voltage conversion | High efficiency but less isolation |

| Typical Applications | Medical equipment, electronics, telecom | Power distribution, industrial motors | Cost-effective power adjustments |

Voltage Conversion and Power Conditioning

One crucial function of an isolation transformer is voltage conversion, which transforms the input voltage into a suitable output voltage for various applications. This ability to adapt voltage levels makes them particularly useful in environments with fluctuating power supplies or specialized equipment that requires specific voltage levels.

An isolation transformer is sometimes referred to as a safety device because it enhances overall electrical safety. By providing potential separation, it protects users and equipment from electrical hazards, such as high voltage, short circuits, and electrostatic discharge. It also prevents capacitive coupling, which occurs when an unintended electrical connection forms between conductive parts, leading to the transfer of electrical energy or interference.

An isolation transformer enhances potential separation between circuits, ensuring safe and stable power flow to connected devices. It plays a crucial role in EMI protection, blocking electromagnetic interference that can disrupt sensitive equipment. By offering noise reduction, an isolation transformer minimizes electrical disturbances and ground loop issues in both industrial and medical environments. Additionally, its ability to provide voltage conversion makes it versatile for various power requirements, while its power conditioning capability ensures consistent, clean energy delivery for optimal equipment performance.

Isolation Transformer Industrial Applications

An isolation transformer is essential in various industries, including healthcare, telecommunications, and manufacturing. For example, healthcare facilities play a crucial role in safely isolating medical equipment from the main power source, preventing electrical hazards and ensuring the well-being of patients and staff.

In telecommunications, an isolation transformer protects communication equipment from electrical noise and transient voltage spikes, guaranteeing the integrity of data transmission. Manufacturing facilities also rely on them to provide a stable, isolated power source for industrial equipment, improving productivity and reducing downtime. Learn about the differences between delta vs wye configurations used in TR connections.

In industrial systems, an isolation transformer is essential for power conditioning and noise reduction, protecting automated machinery and control circuits. In medical devices, they provide critical potential separation to safeguard patients and equipment from electrical faults. In telecommunications, these transformers provide EMI protection and ensure stable voltage conversion, thereby maintaining uninterrupted data flow and preventing interference that could compromise sensitive communication equipment.

Faraday Shields and Advanced EMI/RFI Protection

Including an electrostatic or Faraday shield within an isolation transformer improves the output voltage quality by blocking the transmission of high-frequency noise between the primary and secondary windings. This shield is particularly useful in applications that require a clean and stable power supply, such as sensitive electronic devices or laboratory equipment.

Performance and Impedance Matching

An isolation transformer ensures impedance matching between the connected devices, optimizing the transfer of electrical energy and reducing signal distortion. Their ability to provide a stable power source, eliminate ground loops, and reduce electrical noise makes them indispensable for various applications.

Selecting an Isolation Transformer

When selecting an isolation transformer, several key factors must be considered, including power rating, voltage rating, and the type of load being driven. Additionally, it is essential to determine the degree of separation required and the presence of any DC components in the input signal to select a suitable device for the application. For specialized voltage applications, read about capacitor voltage transformers.

Comparison of Isolation, Autotransformers, and Control Transformers

| Feature | Isolation Transformer | Autotransformer | Control Transformer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Purpose | Safety, EMI/RFI noise suppression | Efficient voltage conversion | Provides stable, low-voltage power for control circuits |

| Galvanic Separation | Yes (complete separation of circuits) | No (shared winding) | Yes (separate primary and secondary) |

| Noise Reduction | High (blocks ground loops, EMI/RFI) | Minimal | Moderate |

| Voltage Flexibility | Can adapt input/output voltages | Wide range of step-up or step-down | Usually fixed, for control panels |

| Common Applications | Medical, telecom, sensitive electronics | Power distribution, industrial systems | Machine controls, automation panels |

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the benefits of using an isolation transformer in an electrical system?

There are several benefits of using an isolation transformer in an electrical system. One of the most significant benefits is that it provides electrical insulation, which can improve electrical safety by reducing the risk of electric shock. It also protects sensitive equipment from voltage surges and eliminates ground loops, which can cause electrical noise and interfere with signal quality. Additionally, it helps regulate voltage, improve power quality, and provide power conditioning, making it an essential component in many electrical systems.

How does an isolation transformer provide electrical safety?

An isolation transformer provides electrical safety by separating the input and output circuits, preventing the transfer of electrical current between them. As a result, any faults or current leaks in the input circuit will not be transferred to the output circuit, reducing the risk of electric shock. Additionally, grounding is not required, which can further improve electrical safety by eliminating the risk of ground loops or voltage surges. Discover how step-up types increase voltage in our detailed guide on generator step-up transformers.

What is the difference between a step-up and an isolation transformer?

A step-up and an isolation transformer are similar but serve different purposes. A step-up is designed to increase the input voltage to a higher output voltage while providing electrical insulation between the input and output circuits. While a step-up may have multiple windings, It typically has only two windings, one for the input voltage and one for the output voltage, with no direct electrical connection between them.

How does an isolation transformer reduce electrical noise in a circuit?

An isolation transformer reduces electrical noise in a circuit by providing galvanic insulation between the input and output circuits. As a result, any electrical noise, such as electromagnetic interference (EMI) or radio frequency interference (RFI), will be prevented from passing through. Additionally, any capacitively coupled signals, which can cause electrical noise, will be blocked.

What is galvanic isolation, and how is it related to an isolation transformer?

Galvanic insulation is the separation of two circuits to prevent the flow of electrical current between them. In an isolation transformer, galvanic insulation is achieved using two windings with no direct electrical connection. This design prevents the transfer of electrical noise, DC components, or capacitively coupled signals between the two circuits.

Can an isolation transformer be used to regulate voltage in an electrical system?

An isolation transformer can be used to regulate voltage in an electrical system to some extent. However, its primary purpose is to provide electrical insulation and reduce electrical noise, rather than regulate voltage. If voltage regulation is required, a voltage TX or a voltage regulator should be used instead. Nevertheless, it can improve the quality of the input voltage and provide power conditioning, which can indirectly improve voltage regulation in the system. Explore the importance of electrical power units in modern energy distribution systems.

Related Articles

Transformer Types and Their Applications

Transformer types include power, distribution, and instrument units, each designed for specific roles. Step-up, step-down, single-phase, and three-phase transformers provide voltage control, energy efficiency, and electrical safety across residential, industrial, and utility systems.

What are the Transformer Types?

Transformer types are classifications of electrical transformers based on their purpose, design, and application. They vary by structure and use in power systems:

✅ Power, distribution, and instrument transformers for specific functions

✅ Step-up, step-down, single-phase, and three-phase designs

✅ Applications in residential, industrial, and utility networks

Electrical Transformer Maintenance Training

Substation Maintenance Training

Request a Free Training Quotation

Various transformer types are indispensable components in modern electrical systems. By examining the various types of transformers, we gain insights into their diverse applications and functionality. For example, power and distribution transformers ensure the effective transmission and distribution of electrical energy, while isolation transformers provide safety measures for users and devices. Autotransformers present an efficient alternative for particular applications, and step-up and step-down transformers cater to the voltage needs of various devices. Three-phase transformers enable efficient power distribution in industrial and commercial settings, and single-phase transformers are designed for residential use. As we expand our understanding of these essential components, we can develop more advanced and efficient electrical systems to benefit the world.

Transformer Types Comparison Table

| Transformer Type | Primary Purpose | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Power Transformer | Step up or step down voltage at high levels | Generating stations, transmission substations |

| Distribution Transformer | Reduce voltage for end users | Residential neighborhoods, commercial areas |

| Isolation Transformer | Provide electrical isolation and noise reduction | Sensitive electronics, medical/lab equipment |

| Autotransformer | Compact, efficient voltage regulation | Voltage adjustment, impedance matching |

| Step-Up Transformer | Increase voltage for long-distance transmission | Power plants, transmission lines |

| Step-Down Transformer | Decrease voltage for safe device use | Industrial machines, appliances, local grids |

| Three-Phase Transformer | Stable AC supply and efficient power distribution | Industrial facilities, commercial systems |

| Single-Phase Transformer | Supply electricity in single-phase systems | Residential power, small businesses |

| Toroidal Transformer | High efficiency, low noise, minimal interference | Audio equipment, sensitive electronics |

| Instrument Transformer | Scale down current/voltage for measurement | Monitoring, metering, protective relays |

In the modern electrical landscape, transformers play a critical role in transmitting, distributing, and utilizing electrical energy. These devices transfer AC power from one circuit to another by altering voltage and current levels. To fully understand their applications and functionality, it is crucial to delve into the concept of different transformer types. In this article, we will explore the various types of transformers and their uses and incorporate additional keywords to provide a clearer understanding of their operations.

Power and Distribution Transformers

Power transformers, typically large, are employed in generating stations or transmission substations. They manage high voltage levels and substantial amounts of electrical energy. Their primary role is to step up the voltage produced by power plants before transmitting it over long distances, which minimizes energy loss in the form of heat. Moreover, they can step down the voltage when necessary, such as at the receiving end of a transmission line.

Distribution transformers, conversely, are utilized in the final stages of the electrical distribution network. They lower the voltage to levels suitable for commercial and residential applications. Unlike power transformers, they are smaller, handling lower voltages, making them ideal for deployment in densely populated areas.

Isolation and Autotransformers

Isolation transformers provide electrical isolation between two circuits. These transformers feature primary and secondary windings that are not electrically connected, creating a protective barrier against electric shocks. Furthermore, they help safeguard sensitive electronic devices from voltage surges or electrical noise by ensuring they are connected to the secondary winding, thereby avoiding any direct connection to the primary side.

Auto transformers are distinct from conventional transformers because they possess only a single winding shared by the primary and secondary sides. This configuration makes them more compact, energy-efficient, and cost-effective, rendering them perfect for specific applications such as voltage regulation or impedance matching. In addition, the number of turns in the single winding determines the ratio of the input and output voltages.

Step-Up, Step-Down, and Phase Transformers

Step-up transformers and step-down transformers are designed to modify voltage levels. A step-up transformer elevates the output voltage from the input voltage, resulting in a higher voltage level. On the other hand, a step-down transformer diminishes the output voltage, making it suitable for devices requiring lower voltage levels. Both types of transformers are instrumental in tailoring electrical systems to accommodate the requirements of various devices and appliances.

Three-phase transformers cater to three-phase electrical systems, predominantly found in industrial and commercial environments. These transformers comprise three single-phase transformers interconnected in specific configurations, such as delta or wye. They facilitate efficient power distribution and minimize voltage fluctuations within the system, ensuring a stable supply of AC power to the connected devices.

Single-phase transformers are utilized in single-phase electrical systems, with their primary and secondary windings connected in series or parallel configurations, depending on the desired output voltage. These transformers are commonly employed in residential settings, providing a reliable source of power to household appliances.

Toroidal and Instrument Transformers

Toroidal transformers, named after their doughnut-like torus shape, are known for their exceptional efficiency and minimal electromagnetic interference. In addition, their compact size and low noise output make them the go-to choice for audio equipment and other sensitive electronic devices.

Measurement instruments play a crucial role in monitoring and maintaining electrical systems. Transformers, especially instrument transformers, are key components in this process. Instrument transformers are specifically designed for use with measurement instruments, allowing them to operate at lower voltage and current levels while still providing accurate readings. This helps maintain a safe working environment for technicians and engineers with high-voltage electrical systems.

How Transformers Work

The process through which a transformer transfers electrical energy relies on the principle of electromagnetic induction. This involves winding transformers with primary and secondary windings around a common magnetic core. When an AC voltage is applied to the primary winding, it generates a magnetic field that induces a voltage in the secondary winding, effectively transferring electrical energy between circuits.

Primary and secondary windings in transformers are essential in achieving the desired voltage conversion. The number of turns in these windings determines the voltage transformation ratio, directly affecting the output voltage provided to the secondary side of the transformer. By selecting the appropriate winding configuration and number of turns, engineers can design transformers tailored to specific applications and requirements.

Conclusion

Understanding the various transformer types and their applications is critical for efficient and safe electrical systems. Power and distribution transformers facilitate the effective transmission and distribution of electrical energy, while isolation transformers offer protection against potential electrical hazards. Autotransformers provide cost-effective solutions for niche applications, while step-up and step-down transformers cater to diverse device requirements. Three-phase transformers promote efficient power distribution in commercial and industrial settings, whereas single-phase transformers serve residential applications. Additionally, toroidal transformers are favored in sensitive electronic devices and audio equipment due to their compact design and minimal interference.

Generator Step Up Transformer

A Generator step up transformer increases the generator output voltage to transmission levels, supporting power plants, substations, and grid integration. It enhances efficiency, minimizes losses, and stabilizes electrical systems in both generation and distribution networks.

What is a Generator Step Up Transformer?

A generator step up transformer (GSU) raises voltage from a generator to transmission levels for efficient long-distance power delivery.

✅ Boosts generator voltage for grid integration

✅ Enhances efficiency and reduces transmission losses

✅ Supports power plants and substations in electrical systems

A GSU is a critical component in modern power systems, acting as the vital link between electricity generation and its efficient transmission across long distances. For electrical professionals, understanding the intricacies of GSUs is essential for ensuring reliable power delivery and maintaining the stability of the power grid. This article explores the fundamental principles, design variations, and maintenance aspects of GSUs, offering valuable insights into their role in power generation, transmission, and distribution. By exploring topics such as voltage ratings, cooling systems, insulation, and testing procedures, readers will gain a comprehensive understanding of these essential power transformers and their crucial role in ensuring the reliable operation of electrical infrastructure. To optimize performance and minimize heat losses in GSUs, it’s essential to understand transformer losses and their impact on efficiency across the grid.

Electrical Transformer Maintenance Training

Substation Maintenance Training

Request a Free Training Quotation

Power Generation and GSUs

GSUs are essential components in a wide variety of power generation schemes. Whether it's a conventional thermal power plant fueled by coal or gas, a nuclear power station, or a renewable energy facility harnessing the power of wind, solar, or hydro, GSUs play a crucial role in preparing the generated electricity for transmission. The generator voltage produced by these power sources typically falls within the range of 13 kV to 25 kV. While sufficient for local distribution within the power plant, this voltage level is too low for efficient transmission over long distances due to the inherent resistance of transmission lines. This is where GSUs come in, stepping up the voltage to much higher levels, often reaching hundreds of kilovolts, to facilitate efficient power delivery across the power grid. In environments where oil-filled designs are impractical, dry-type transformers provide an alternative solution for reliable operation.

Transmission & Distribution

The high voltage output from the GSU transformer is fed into the transmission lines that form the backbone of the power grid. These high-voltage transmission lines enable the efficient long-distance transportation of electricity with minimal losses. By increasing the voltage, the current is reduced, which in turn minimizes the energy lost as heat in the transmission lines. This efficient transmission system ensures that electricity generated at power plants can be reliably delivered to distant cities and towns. While GSUs increase voltage, step down transformers perform the opposite function, reducing voltage levels for distribution and end-user applications.

Transformer Design & Technology

GSU transformers are engineered to withstand the demanding conditions of continuous operation and high voltage levels. They are typically large, custom-built units with robust designs to handle the immense electrical stresses and thermal loads. Different design considerations, such as core and shell types, cooling methods (oil-filled or dry-type), and insulation materials, are crucial to ensure the transformer's long-term reliability and performance within the power grid. For metering and protection alongside GSUs, instrument transformers such as CTs and PTs ensure accurate monitoring and safety.

Reliability & Maintenance

Given their critical role in the power system, the reliability of GSUs is paramount. Regular maintenance, condition monitoring, and diagnostic testing are essential to ensure their continued operation and prevent costly outages. Utilities and power plant operators employ various techniques to assess the health of these transformers, including analyzing oil samples, monitoring temperature and vibration levels, and performing electrical tests. These proactive measures help to identify potential issues before they lead to failures and disruptions in power supply. Similar in importance, a current transformer is designed to safely measure high currents in power plants and substations where GSUs are operating.

Efficiency & Losses

While GSUs are designed for high efficiency, some energy losses are inevitable. These losses occur primarily in the core and windings of the transformer and are influenced by factors such as the core material, winding configuration, and load conditions. Minimizing these losses is crucial for overall system efficiency and reducing operating costs. Transformer manufacturers continually strive to enhance efficiency by utilizing advanced materials, optimizing designs, and implementing innovative cooling systems.

Cooling Systems

Effective cooling is crucial for the reliable operation of GSUs, especially given their high operating loads. Various cooling methods are employed, including Oil Natural Air Natural (ONAN), Oil Natural Air Forced (ONAF), Oil Forced Air Forced (OFAF), and Oil Directed Water Forced (ODWF). These methods employ various combinations of natural and forced circulation of oil and air, or water, to dissipate heat and maintain optimal operating temperatures within the transformer.

Insulation & Dielectric Strength

The high voltage levels present in GSUs necessitate robust insulation systems to prevent short circuits and ensure safe operation. The insulation materials used in these transformers must have high dielectric strength to withstand the electrical stresses. Factors such as voltage levels, temperature, and environmental conditions influence the choice of insulation materials and the design of the insulation system. While GSUs raise generator voltage for transmission, a control transformer provides stable, lower-level power for control circuits and equipment.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is a GSU used in a power plant?

Step-up transformers are used in power plants because they increase the voltage of the electricity generated, which is necessary for efficient long-distance transmission. Higher voltage levels result in lower current, which minimizes energy losses in the transmission lines. This ensures that electricity can be delivered to consumers far from the power plant with minimal losses.

What is the typical voltage rating of a generator step-up transformer?

The voltage rating of a GSU varies depending on the specific application. However, typical generator voltage ranges from 13 kV to 25 kV, while the secondary voltage (after step-up) can range from 66 kV to 765 kV or even higher for long-distance transmission. The specific voltage levels are determined by factors such as the generator output, the transmission system voltage, and the desired level of efficiency.

What are the different types of generator step-up transformers?

GSUs can be broadly categorized into oil-filled and dry-type transformers. Oil-filled transformers utilize insulating oil for both cooling and insulation, whereas dry-type transformers rely on air or gas insulation. Within these categories, there are further variations in core type (shell or core) and insulation materials. The choice of GSU type depends on factors such as the transformer's size, voltage rating, environmental conditions, and safety considerations.

How does a generator step-up transformer handle surges and overloads?

GSUs are designed to withstand temporary surges and overloads that can occur in the power system. They incorporate protective devices such as surge arresters to divert excess voltage caused by events like lightning strikes. Additionally, relays are used to automatically disconnect the transformer in the event of severe faults, such as short circuits, thereby preventing damage to both the transformer and the power system.

What are the key maintenance activities for a generator step-up transformer?

Key maintenance activities for GSUs include:

-

Oil Analysis: Regularly analyzing the insulating oil for signs of degradation or contamination.

-

Visual Inspections: Inspecting the transformer for any physical damage, leaks, or signs of overheating.

-

Electrical Testing: Performing tests like winding resistance measurements and insulation resistance tests to assess the transformer's electrical integrity.

-

Infrared Thermography: Using thermal imaging to detect hot spots that may indicate potential problems.

By adhering to a comprehensive maintenance program, power plant operators can ensure the long-term reliability and performance of their GSU transformers.

Related Articles