Electricity Windmill Explained

Electricity windmill converts wind energy into electrical power via rotor blades, generator, gearbox, and inverter, supporting renewable energy, grid integration, power electronics, and efficient electricity production with modern control systems and variable-speed drives.

Electricity Windmill Fundamentals

Electricity windmill Mankind been harnessing the wind's energy for many years. From Holland to traditional farms around the world, old style windmills were used in the past for pumping water through primative irrigation systems or used to grind grain. Then, the wind turned large "sails" which were connected by a long vertical shaft that was attached to a grindnig machine or to a wheel that turned and drew water from a well. Today's wind turbine generators can utilize the clean energy of high wind speeds to turn large metal blades which in turn spins a generator that manufactures electric power. For a deeper overview of modern designs, the resource at windmills for electricity explains key configurations used by utilities today.

Electricity windmill turbines, unlike the machines of old, are mounted on very tall towers in order to capture the most wind energy available. At 100 feet (30 meters) or more above ground, wind turbines can take advantage of the faster and less turbulent wind. Turbines catch the wind's energy with their propeller-like blades. Usually, two or three blades are mounted on a shaft to form a rotor. If you're curious how these rotating blades ultimately power homes, see how turbines generate electricity through step-by-step conversion processes.

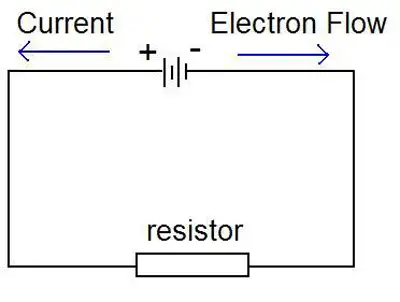

A blade acts much like an airplane wing. When the wind blows, a pocket of low-pressure air forms on the downwind side of the blade. The low-pressure air pocket then pulls the blade toward it, causing the rotor to turn. This is called lift. The force of the lift is actually much stronger than the wind's force against the front side of the blade, which is called drag. The combination of lift and drag causes the rotor to spin like a propeller, and the turning shaft spins a generator to make power. The rotating shaft must be matched to an electricity generator with appropriate gearing and controls to optimize output.

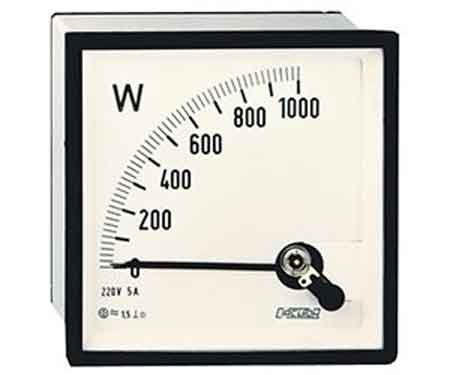

In recent years, governments have invested enormous amounts of (taxpayer) money in electricity windmill "wind farms" to generate large amounts of energy from large and small wind turbines that take advantage of high winds. These wind systems or energy systems use wind turbine power to create electricity. Other energy sources like solar power do not produce as much electricity. The only problem with wind generated power is that when the wind stops, so does the generator and therefore the electric power production. Electric power cannot be produced and stored for consumption later. Therefore, wind power can only be counted on mostly when the wind is blowing at optimal speeds and only in locations where the prevailing winds are such that it makes economic sense to build these power plants and this may not be when and where the power is needed. Grid planners track regional electricity production profiles to determine how much wind capacity can be integrated without compromising reliability. As part of a balanced portfolio, policy makers also evaluate alternative electricity options that can complement variable wind resources.

Stand-alone electricity windmill turbines are typically used for water pumping or communications. However, homeowners, farmers, and ranchers in windy areas can also use wind turbines as a way to cut their power bills. For off-grid ranch operations, understanding the interplay between pumps and water electricity systems helps size batteries and controllers correctly.

Small electricity windmill systems also have potential as distributed energy resources. Distributed energy resources refer to a variety of small, modular power-generating technologies that can be combined to improve the operation of the electric power delivery system. In some regions, small-scale hydroelectricity can serve as a firm companion to wind in distributed portfolios.

_1497153600.webp)

_1497176752.webp)