Power System Analysis Explained

By R.W. Hurst, Editor

Power System Analysis enables load flow studies, fault calculations, stability assessment, state estimation, and contingency analysis for grids, integrating SCADA data, protection coordination, and reliability planning to optimize transmission, distribution, and generation performance.

What Is Power System Analysis?

Power System Analysis models grid behavior to ensure stability, reliability, efficiency, and secure operation.

✅ Load flow, short-circuit, and transient stability studies

✅ State estimation, SCADA integration, and contingency analysis

✅ Protection coordination, reliability assessment, and optimization

Power system analysis (PSA) is an essential electrical system component. It helps to ensure that the electrical system operates efficiently, reliably, and safely. Power flow analysis, fault study, stability investigation, renewable energy integration, grid modernization, and optimization techniques are all essential concepts in PSA. As our society continues to rely heavily on electricity, PSA will remain a vital tool for ensuring the stability and reliability of the electrical system. For foundational context on how electricity underpins these studies, see this primer on what electricity is and how it behaves.

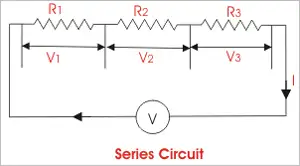

One of the critical concepts in PSA is power system modelling. Modelling is creating a mathematical model of the electrical system. This model includes all the system components, such as generators, transformers, transmission lines, and distribution networks. Modelling is essential as it provides a detailed understanding of the system's workings. Engineers commonly begin by drafting a single-line diagram to visualize component interconnections and power paths.

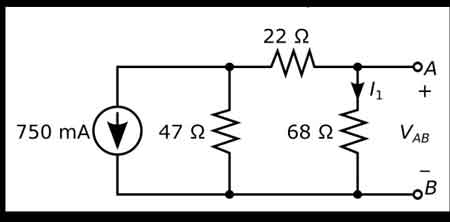

Another critical concept in PSA is power flow investigation, also known as load flow investigation. Power flow analysis calculates the electrical system's voltages, currents, and power flows under steady-state conditions. A power flow study helps determine whether the electrical system can deliver electricity to all the loads without overloading any system component. The results of the power flow investigation are used to plan the system's expansion and ensure that it operates efficiently and reliably. In practice, load-flow outputs are interpreted within the broader context of electric power systems to validate voltage profiles and thermal limits.

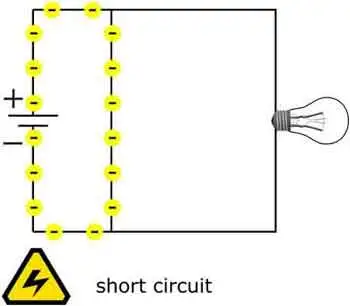

Fault study is another crucial component of PSA. A fault study is a process of analyzing the system's behaviour during a fault condition. This needs a short circuit analysis. A fault is abnormal when the system has a short or open circuit. A fault study helps to determine the fault's cause and develop strategies to prevent or mitigate the effects of faults in the future.

Stability investigation is also an important aspect of PSA. Stability investigation is the process of analyzing the system's behaviour under dynamic conditions. For example, the system is subject to dynamic disturbances, such as sudden load or generator output changes, which can cause instability. Stability investigation helps ensure the system can withstand these disturbances and operate reliably.

The transient investigation is another key concept in PSA. The transient study analyzes the electrical system's behaviour during transient conditions, such as switching operations or lightning strikes. A brief investigation helps ensure the system can withstand these transient conditions and operate reliably.

Renewable energy integration is an emerging concept in PSA. As more renewable energy sources, such as wind and solar power, are integrated into the energy system, PSA becomes increasingly essential to ensure the stability and reliability of the electrical system. Understanding how generation mixes are formed benefits from a primer on how electricity is generated across thermal, hydro, and renewable technologies.

Grid modernization is also a crucial aspect of PSA. As the system ages, it becomes increasingly important to modernize the grid to ensure that it can meet the demands of modern society. Therefore, PSA is used to develop strategies to modernize the grid and ensure it operates efficiently, reliably, and safely. Many modernization roadmaps align with the evolving architecture of the electricity grid as utilities adopt automation, advanced metering, and distributed resources.

Finally, protection coordination and optimization techniques are essential components of PSA. Protection coordination involves developing strategies to protect the electrical system from faults and other abnormal conditions. Optimization techniques involve developing strategies to optimize the system's operation and ensure it operates efficiently and reliably. Because reactive power and losses affect dispatch, monitoring and improving power factor can materially enhance system efficiency.

What is power system analysis, and why is it important?

PSA analyzes the electrical system to ensure it operates efficiently, reliably, and safely. Therefore, it is crucial to identify potential problems before they occur and develop strategies to prevent or mitigate the effects of these problems. In addition, PSA is important because it helps ensure that the electrical system can meet the demands of modern society, which relies heavily on electricity.

How is power flow analysis performed?

Power flow analysis, or load flow analysis, is performed using a mathematical model. The model includes all the power system components, such as generators, transformers, transmission lines, and distribution networks. A power flow study calculates the electrical system's voltages, currents, and power flows under steady-state conditions. The results of the power flow investigation are used to plan the electrical system's expansion and ensure that it operates efficiently and reliably. These studies also quantify reactive power behavior, making concepts like what power factor is directly applicable to planning and operations.

What is fault analysis, and how is it used?

Fault analysis is analyzing the system's behaviour during a fault condition. A fault is abnormal when the system has a short or open circuit. A fault study is used to determine the fault's cause and develop strategies to prevent or mitigate the effects of faults in the future. Fault analysis is crucial in ensuring the safety and reliability of the electrical system.

What are the different stability study techniques used?

Several stability investigation techniques are used in PSA to measure transient, small-signal, and voltage stability. Transient stability is used to analyze the behaviour of the distribution under dynamic conditions, such as sudden changes in load or generator output. Small-signal stability measurement analyzes the system's behaviour under small disturbances. Finally, voltage stability measurement is used to analyze the system's behaviour under steady-state conditions and determine the system's voltage limits.

How does renewable energy integration affect power system analysis?

Renewable energy integration is an emerging concept in PSA. As more renewable energy sources, such as wind and solar power, are integrated into the electrical system, PSA becomes increasingly essential to ensure the stability and reliability of the system. Renewable energy sources are intermittent, which can cause fluctuations in the system. PSA is used to develop strategies to integrate renewable energy sources into the system while ensuring its stability and reliability.

What are the challenges of grid modernization, and how does power system analysis help overcome them?

Grid modernization is a crucial aspect of PSA. As the system ages, it becomes increasingly important to modernize the grid to ensure that it can meet the demands of modern society. Grid modernization involves upgrading the system to incorporate new technologies, such as smart grid technologies and renewable energy sources. The challenges of grid modernization include the need for new infrastructure, the integration of new technologies, and new regulatory frameworks. PSA is used to develop strategies to overcome these challenges and to ensure that the electrical system operates efficiently, reliably, and safely.

How can optimization techniques improve system efficiency and reliability in power system analysis?

Optimization techniques can be used in PSA to improve system efficiency and reliability. These techniques involve developing strategies to optimize the system's operation and ensure it operates efficiently and reliably. For example, optimization techniques can determine the optimal generation and transmission of power, improve load forecasting, and develop strategies to reduce energy consumption. PSA is crucial in developing and implementing these optimization techniques, which help improve the electrical system's overall efficiency and reliability, leading to a more sustainable and cost-effective electrical power system.